It is difficult for a weakened cod stock to recover if the right conditions are not in place. A combination of historical overfishing, oxygen depletion, liver parasites and seal predation makes the eastern cod stock particularly vulnerable. In the Åland Sea, however, cod seem to be doing well. Oxygen conditions are better and cod have good growth and condition – despite liver parasites and grey seals. To understand what causes the marked difference in growth between cod in the Åland Sea and the southern Baltic Sea, Yvette Heimbrand, a researcher at SLU Aqua, and her research colleagues will investigate how oxygen deficiency and liver parasites individually, and in combination, affect the growth and well-being of cod. The aim is to increase understanding of cod growth challenges and thereby contribute to the development of management measures.

It is almost five years since the ban on fishing Baltic cod was introduced, but the eastern cod stock still shows no signs of recovery. It is slow growing, small and often lean. Yvette and her fellow researchers are working to find out why, and her dedication and knowledge of cod is hard to miss when she talks about the project.

We are collecting cod from both the Åland Sea and the Bornholm Deep in the southern Baltic Sea to compare cod growth hormone levels and relate it to liver parasite load through direct counts of parasites and to oxygen deprivation through analyses of otoliths, which are the cod’s ear stones, she explains.

The Sea of Åland and the Bornholm Deep differ in depth, salinity and oxygen conditions. While the Åland Sea has an even salinity of about 7 parts per thousand and oxygen-rich water all the way down to the bottom at a depth of 250-300 metres, parts of the Bornholm Deep suffer from severe oxygen deficiency and dead bottoms. There, salinity is around 7-8 parts per thousand at the surface and at a depth of 100 metres, salinity goes up to 14-16 parts per thousand.

The reason why the Åland Sea has better oxygen conditions is due to the threshold into the Åland Sea that blocks oxygen-poor water from the southern parts of the Baltic Sea. In addition, the Åland Sea has currents that cause the water to mix and become oxygen-rich right down to the bottom.

Salinity is important for the success of cod reproduction. Fertilised eggs also require a certain salinity to be able to float in the open water and not risk sinking to the bottom where there may be a lack of oxygen.

Oxygen depletion takes its toll

Yvette and her colleagues will investigate how cod growth is affected by anoxia through controlled experiments in the laboratory of collaborators at DTU Aqua in Denmark. Cod in one tank will be exposed to oxygen deficiency, while cod in another tank will be in water with good oxygen conditions. Otherwise, the water in the tanks will have the same salinity and the cod will be fed identical diets. Using microchemical analyses of the otoliths, which are located under the brain in the fish’s head, Yvette will gather important information about the cod’s life history.

In these two tanks, oxygen deficiency experiments are performed. Photo: Sune Riis Sørensen.

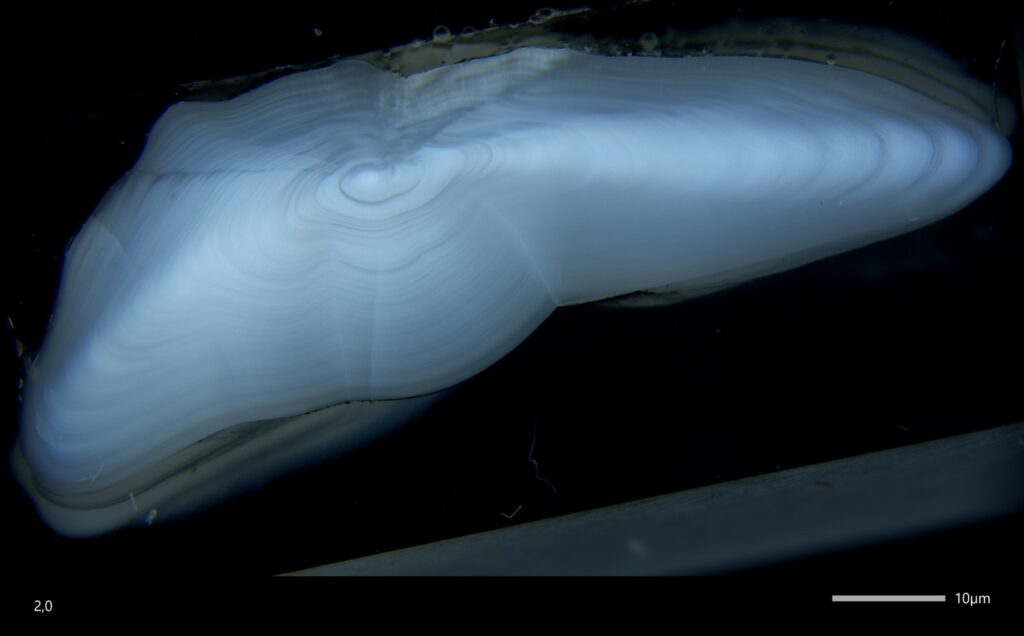

– Like the annual rings of a tree, the otoliths of fish grow throughout their lives and store trace elements that reflect, for example, salinity, oxygen deficiency, growth and metabolic activity. So we can find out a lot about cod by analysing otoliths, including how their chemical composition changes during anoxia, says Yvette.

However, lack of oxygen not only affects the growth and condition of cod, but also the availability of food.

– When we have collected cod from the Åland Sea, the cod’s stomach has often been full of Saduria entomon, a benthic crustacean that the cod eat. In the southern part of the Baltic Sea, there are not as many benthic animals due to the oxygen-poor deep bottoms, which of course can affect the cod’s access to food, says Yvette.

On the left you can see an entire otolith, the cod’s hearing stone. The image on the right shows what an otolith might look like after a cross-section through it. Notice the annual rings, which, like a tree, form as the cod grows. Photo: Yvette Heimbrand.

Worms in the liver

The method the researchers use to investigate how fish are affected by parasitic infestations is not for the squeamish.

– First we weigh and measure the liver, and to get an index of how infested the liver is, we then dissolve it and count the number of worms.

Yvette and her colleagues can already see that smaller cod from the Åland Sea have few or no parasites at all, while the larger and older cod can have several hundred maggots in their livers.

– There seems to be a difference in the amount of liver worms depending on which area of the Baltic Sea the cod comes from, but we will know more about this only after we have analysed our data, Yvette explains.

Left: A small and lean cod. Photo: Jukka Pönni. Centre: A large cod from the Åland Sea. Right: A cod liver infested with parasites. Photo: Yvette Heimbrand.

Activities in the brain

But how can the experiments be linked to cod’s ability to grow? Well, by analysing the cod’s brain. The oxygen depletion experiment and the liver parasite analyses, individually and in combination, will be linked to the levels of growth hormone found in the cod’s pituitary gland (a gland in the cod’s brain).

– The levels of growth hormone, which is produced in the pituitary gland, will be examined to compare whether there are differences between cod in the Åland Sea that have good growth and cod in the southern Baltic Sea that have poor growth. We also want to study how growth is affected by the number of liver parasites and the degree of oxygen deficiency to which the fish have been exposed, says Yvette.

The project is unique in its kind. Studies looking at the combined effects of growth hormone, parasites and oxygen deprivation on cod growth have not been carried out so far. In the autumn, the project team plans to carry out further sampling and new cod from the Åland Sea and Bornholm Deep will be caught. After that, a lot of laboratory work and data analysis remains, which Yvette is looking forward to.

– I will be responsible for the microchemical analyses of the cod otoliths and Jane Behrens, a researcher at DTU Aqua, will be in charge of the analyses of the amount of liver parasites and growth hormone. It will be very exciting to compile the results, she says.

So there are many reasons to return to the project in a couple of months. Not least to hear about the results, but also to find out more about how the results can help develop management measures to favour cod growth.

The researchers in the project ‘Do parasites and hypoxia prevent a recovery of Eastern Baltic cod?’ consists of:

– Ulf Bergström, researcher at SLU Aqua

– Yvette Heimbrand, researcher at SLU Aqua

– Jane Behrens, researcher at DTU Aqua

– Karin Limburg, Professor at SUNY Collage of Environmental Science and Forestry in New York, visiting scientist at SLU Aqua

Do parasites and hypoxia prevent a recovery of Eastern Baltic cod? is implemented by the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. Through BalticWater’s programme for research projects and feasibility studies, the project has been granted funding of SEK 1 million for the scientific part of the project. You can read more about the three other funded projects in the article Four new research projects for a living Baltic Sea.