Ecosystem-based – that’s how we want fisheries to be managed in the future. But what does it really mean and how will it be realised in practice? BalticWaters has spoken to experts in Sweden, reviewed reports and looked to Australia as a model.

– I don’t know if it’s entirely feasible to achieve these theoretical goals with the management system we have today, says marine ecologist Sofia Wikström, who has researched the application of the ecosystem approach in Sweden.

‘It means, among other things (…) taking into account that different species in an ecosystem affect each other and that the interaction between humans and the environment often spans several sectors of society,’ writes the Swedish Institute for the Marine Environment in a report from 2019.

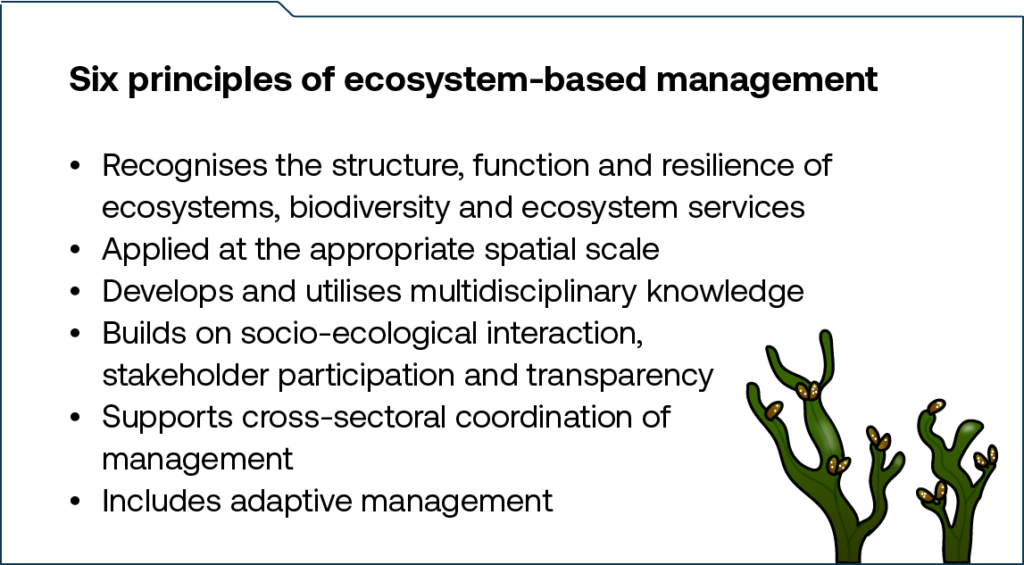

– It is a huge concept that is very difficult to grasp and is used very differently by different people. ‘If you just say “ecosystem-based management” it can mean anything, it helps if you refer to the Malawi principles, says marine ecologist Sofia Wikström at Stockholm University, who also works on BalticWater’s Thriving Bays project.

Source: Swedish Institute for the Marine Environment (Rouillard m fl. 2018; Langhans m fl. 2019)

The Malawi Principles originate from the 1993 UN Convention on Biological Diversity, which aims to achieve ecological, economic and social sustainability in the use of ecosystems and natural resources. They usually form the theoretical basis for ecosystem-based management models. But in practice, things can look very different, as a report co-authored by Sofia Wikström shows. The report, published in 2020, concerns practical experiences of EBM from Swedish marine, fisheries and water management.

– The report came about through a call for proposals at the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, at the direct request of the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management (HaV). One of the tasks of these agencies is to make marine, fisheries and water management more ecosystem-based. They therefore asked us researchers to help them map out what has been done so far, what the bottlenecks are and what the problems are.

The authors of the report describe the process of moving towards ecosystem-based management as like changing the course of a cargo ship – a bit bumpy, heavy and difficult to navigate. The report shows that Sweden has made some progress towards a more ecosystem-oriented approach to marine and fisheries management, but that there are still many challenges.

Among other things, the report calls for better communication and collaboration between different actors and clearer governance and follow-up by authorities. But perhaps the main problem lies in the nature of the basic system in Sweden. It is difficult to apply a round model to an angular administration.

The twelve principles of the ecosystem approach (Malawi Principles)

1. Community interests determine management objectives

2. Management should be decentralised to the lowest practicable level and involve everyone in order to balance local and public interests

3. Those implementing management should consider the impacts (real or potential) on neighbouring or other ecosystems

4. Understanding the value of the ecosystem from an economic perspective is fundamental. Management should, in part: a) reduce subsidies that lead to biodiversity loss; b) create incentives that favour biodiversity and sustainable use; c) integrate costs and benefits in a given ecosystem as far as possible.

5. Maintaining the structure and functioning of ecosystems to sustain ecosystem services should be a priority objective, as functioning ecosystems have the capacity to resist change

6. Ecosystems should be managed within the limits of their functions, applying the precautionary principle

7. The ecosystem approach should be applied at the appropriate scale in time and space

8. Recognising that time lags affect ecosystem processes, long-term management objectives should be set

9. Management must accept that change is inevitable

10. The ecosystem approach should integrate biodiversity conservation and sustainable use

11. Recognises that the ecosystem approach should take into account all types of relevant information, including scientific and traditional and local knowledge, innovations and practices

12. The ecosystem approach should involve all relevant sectors of society and scientific disciplines

Source: HaV

– The idea of EBM, as described in research for example, is that it should be a coherent management cycle that includes all important aspects and actors. This is not how management is organised in Sweden. It is a little difficult to push for this model as the management looks today, but they have still tried to do it. We write a lot in the report about measures in different parts of the cycle ending up with different bodies for implementation. It becomes a problem if someone sets the goals and someone else has to fulfil them. This places very high demands on good communication and agreement.

Sofia Wikström. Photo: BalticWaters

The report looked at how other countries have implemented EBM and interviewed researchers and experts from different parts of the world.

– You recognise a lot of things, it’s very much the same problems you face in different countries. It shows that it is difficult.

However, there are some countries that have made more progress than others, such as Norway and Australia.

– It is no coincidence that countries with large maritime economies have worked longer on this and made some progress.

Relationship with the fishing industry

In particular, Australia, but perhaps especially Tasmania and Western Australia, is often held up as a model for successful ecosystem-based management. Therefore, BalticWaters has contacted Professor Caleb Gardner at the Institute of Marine and Antarctic Studies at the University of Tasmania to get clarity on how EBM is viewed in Australia.

– For us, it’s usually as simple as considering fishing effects in addition to changes in target species.

He gives five reasons why Australian fisheries management has been successful from an ecosystem perspective (see box on the right). He also explains that management is characterised by close collaboration with the fishing industry, where there are both opportunities and challenges.

The introduction of the quota system in the country has meant that the big fishing companies in Australia are controlled by investment firms that want higher fishing quotas and have little regard for the impact on fish stocks.

– Ecosystem-based management doesn’t do much to address that particular problem, says Caleb Gardner.

Another prominent name in Tasmanian research circles is Professor Craig Johnson, who has been an important cog in the wheel of ecosystem-based development of fisheries management in the region. Swedish Jessica Nilsson, who now works at the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management, did her doctoral studies with Johnson and she says that he himself took the initiative to contact the managers with data he had collected over decades, and it has continued along that path.

– Scientists work closely with managers to ensure sustainable fisheries. This makes managers and politicians look accountable to their constituents. Australia’s management is generally very broad – involving indigenous peoples, fishers, industry, local communities and all relevant government agencies. There is very close co-operation between scientists, government and the state. I think this great co-operation is the reason why they have done so well.

Reasons for success in Australian fisheries management according to Professor Caleb Gardner:

1. A commitment to risk-based approaches to ecosystem management in fisheries. One of the reasons for developing risk-based frameworks, which started in Western Australia and were then implemented in the rest of the country, was scepticism about the methods used elsewhere. ‘The best example is the widespread use of MPAs (marine protected areas) elsewhere in the world. Australian fish scientists were sceptical of this type of ideological approach over effective meaningful action via ecosystem-based approaches.’

2. Good political leadership.

3. Ecosystem management has been broken down into clear categories of bycatch, TEPS (threatened, endangered, and protected species), ecosystems and habitats, which made the process logical and more manageable. ‘This is not unique to Australia and is widely used elsewhere (e.g. Marine Stewardship Council MSC), but it permeates discussions and ideas among policy makers in Australia.’

Jessica Nilsson currently works with issues relating to the Arctic at the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management, but during her studies in Tasmania she made a comprehensive comparison of 21 fishing areas around the world to identify opportunities and obstacles to ecosystem-based management.

– I researched what ecosystem-based management means and then put together a model to identify the key biological, social, legal, management and economic factors for sustainable fisheries.

She then collected data from different fisheries, including the cod fishery in Canada, the sardine fishery in Namibia and the eel fishery in the EU, and interviewed experts from the different regions.

– I then carried out various risk analyses to see whether or not a stock is at risk of collapse depending on various factors.

Among the stocks categorised as collapsed, including EU eel fisheries and cod in the Baltic Sea, Nilsson and her co-authors identified several common factors. They often involved migratory species that were slower to reproduce, susceptible to disease and with a high economic value.

– The economic value can push for a collapse. At the same time, it can be seen that there are fisheries that operate differently. For example, in Tasmania, smaller lobsters were caught in order to get an even higher price for them. In that case, what was biologically best was also the most profitable.

Factors for scoring fisheries and examples of criteria within the factors

Biology (including reproduction and migration)

Environment (including Ocean Health Index (OHI) and environmental degradation)

Social/economic factors (including Human Development Index (HDI) and Poverty and Economic Decline Index)

Industry (including commercial value and subsidies)

Governance (including Global Peace Index (GPI) and GINI index)

Management (including scientific assessment of fish stocks and monitoring)

It was important for Jessica Nilsson to get representation from both developing and industrialised countries. The mapping showed that there is no correlation between how wealthy a country is and how well its fish stocks are doing.

– It was interesting to see how developing countries with fewer resources can have sustainable fisheries, and richer countries have collapsed fisheries. It shows that the marine environment is very complex to manage and is constantly changing, and that there are strong economic and political interests.

The best-ranked stocks when all factors (biological, environmental, social/economic, industrial, governance, management) were the Northern Australian prawn fishery and the Western Australian rock lobster fishery. The collapsed eel fishery in the EU and the collapsed toothfish stock in South Africa received the lowest scores. European eel fisheries scored poorly on all six factors.

Jessica Nilsson summarises that a high ranking in several factors is necessary for a fishery to have a high probability of being sustainable and thus meet the criteria for ecosystem-based fisheries management. The sustainable fish stocks in the study all had an average overall score of between 17.1 and 25.1 (out of a possible 30) and over 4 out of 5 scores in biology, governance and industry. An overall key feature to be able to tell if a stock is sustainable or not is to have good data.

– It is fundamentally important to know how much fish we have, what the stocks look like in terms of age, and what the habitats look like, so that we can manage the fish in the best way. You have to make sure you have the best information. If you don’t have good data, you should follow the precautionary principle.

Information and data also include assessments and risk analyses like the one conducted by Jessica Nilsson and her colleagues. Norway and Australia are two countries that have a strong focus on risk analyses in their fisheries management, something that is almost completely absent in Sweden. Three years ago, the research institute RISE completed a four-year project investigating the potential of using and combining ecological risk analysis (ERA) and life cycle assessment (LCA) to move towards more ecosystem-based fisheries management.

– LCA is widely used in society to evaluate products from, for example, fisheries, but there is a lack of methods to evaluate ecological impacts – where ERA has its strength. ERA is used in fisheries management, but does not include, for example, the climate impacts of different management measures. Therefore, they complement each other for a more comprehensive picture. Swedish fisheries management uses neither ERA nor LCA, says researcher Sara Hornborg.

One of the project’s conclusions was that Sweden needs to define management objectives for EBF so that research can evaluate risks, and that Sweden needs to get better at including the ‘human dimension’. This means, for example, the view of equity aspects, i.e. that the common and limited fisheries resource is fairly distributed.

BalticWaters comments:

Today’s fisheries management focuses only on individual fish stocks, without taking into account how they influence and are influenced by each other in the ecosystem. Ecosystem-based fisheries management should look at the big picture – how different fish species and environmental factors interact for holistic and long-term management. By managing fisheries on the basis of the whole ecosystem, management can be adapted to new knowledge and changes. At the same time, it involves more sectors of society and stakeholders, providing a broader perspective. But with its benefits also come challenges. Managing multiple factors simultaneously is more complex than just focusing on individual fish stocks, and it takes time to implement new management systems and work processes. It also requires a good understanding of ecosystem functions, and there are knowledge gaps to be filled. But while we can always know more tomorrow, we already have a lot of knowledge and potential to change fisheries management today. The bigger problem often lies in strong economic and political interests that get in the way.