Environmentally hazardous wash water from ships is pumped into our seas – something that happens all the time and completely openly. BalticWaters has examined the issue of scrubbers – a technology that turned ships’ chimneys down into the sea when emissions to the air had to be limited. The intentions were good, but with the ambition to solve one environmental problem, another has been created.

The environmental impact of global shipping

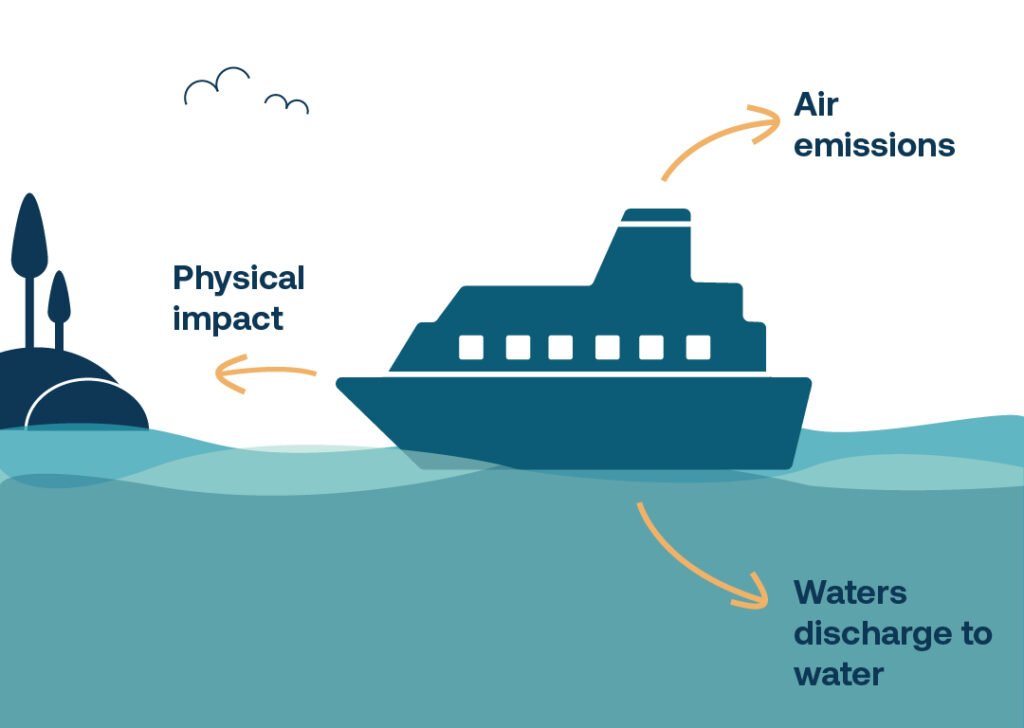

The majority of global freight transportation is currently carried out by maritime transport. Shipping accounts for over 80% of international trade volume and is an important part of countries’ economic growth. Emissions from shipping affect both air and water, and pollution can travel long distances and have a negative impact on the environment far from the source of the emissions. Emissions impair air quality, affect the global climate and have negative effects on ecosystems and human health.

Shipping also causes negative physical impacts on the marine environment, in the form of coastal erosion and sediment resuspension in shallow areas. Increased turbulence in the water column caused by shipping can alter nutrient dynamics and increase plankton mortality, especially in areas with heavy traffic. In addition, the greenhouse gas methane can be released from sediments in the coastal zone as a result of ship movements. At the same time, there are many knowledge gaps about the extent of environmental problems. This applies to the spread of invasive species via ballast water, the effects of noise and artificial light, and the ecological consequences of the increasing amount of chemicals in the sea.

Reduced air emissions at the expense of discharges to sea

With the good intention of reducing harmful sulphur emissions to the air from shipping, gradual regulations have been introduced for global shipping during the 2000s by the IMO (International Maritime Organization), a UN organisation that regulates the shipping industry. To meet the new requirements, ships must either run on low-sulphur fuels or install a cleaning device on board to remove the pollutants. This is where interest in installing an exhaust gas cleaning system (EGCS), also known as a scrubber, comes in. The installation of scrubbers is mainly motivated by the shipping industry’s desire to continue using cheaper heavy fuel oil instead of significantly more expensive fuels with lower sulphur content. More environmentally friendly low sulphur fuels can be up to twice as expensive as high sulphur fuels. The use of heavy fuel oil is also supported by the oil industry, which would otherwise find it difficult to sell such an ‘unrefined’ petroleum product.

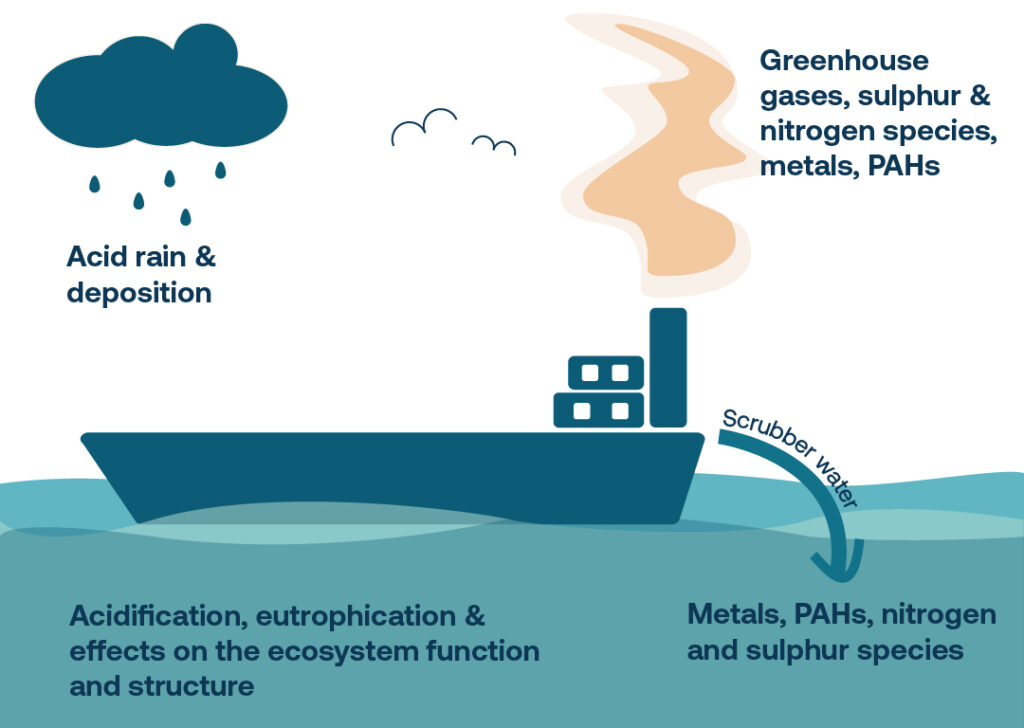

The EGCS system, or scrubber, reduces sulphur emissions to the air, but as a result, heavily polluted wash water is discharged into the sea. Scrubbers are available in different versions – open, closed and hybrid. The simplest and most common type is the open scrubber. It works by pumping large volumes of seawater (usually 500 cubic metres per hour for a medium-sized ship) on board and then releasing it back into the sea after it has passed through the scrubber. The discharged water is highly acidic (usually pH 3, compared to natural pH 8) and contains high concentrations of pollutants. Closed scrubbers also discharge wash water, despite their name, although in smaller volumes. Hybrid scrubbers can switch between open and closed modes.

More about marine fuels:

Alternatives to heavy fuel oil have been developed with the aim of meeting both the restrictions on sulphur content in fuel and greenhouse gas emissions from shipping. However, running on a more environmentally friendly fuel can be twice as expensive for shipping companies. Other ways of reducing emissions include energy efficiency improvements, such as ship design that require less energy for propulsion.

Heavy fuel oil

The most important advantage of heavy fuel oil for shipping companies is its price – it is relatively cheap. To comply with sulphur regulations, ships running on heavy fuel oil must install a scrubber that cleans the exhaust gases of sulphur – but this also creates large amounts of environmentally hazardous emissions into the sea.

Hybrid oils – VLSFO and ULSFO

Hybrid oils or mixed fuels contain lower levels of sulphur than heavy fuel oil – Very Low Sulphur Fuel Oil (VLFSO) has a sulphur content of 0.5% and Ultra Low Sulphur Fuel Oil (ULSFO) has a sulphur content of 0.1%. In the Baltic Sea, there are strict rules on a maximum sulphur content of 0.1%, which can be met by ULSFO. However, these fuels consist of oil industry residues, are toxic and difficult to clean up in the event of a spill. There is also limited information on the chemical compounds contained in hybrid oils.

MGO – Marine gas oil

MGO comprises various types of fuels consisting of distillates that have undergone a refining process. Some marine gas oils consist of hybrids, i.e. gas oil mixed with residual oil. The fuel contains lower levels of sulphur than heavy fuel oil, is more environmentally friendly but also more expensive.

LNG – Liquefied natural gas

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) has the advantage of low sulphur content and clean combustion properties, but it is of fossil origin and can cause methane emissions. It is also a more expensive option for many ship operators, as the ship needs to be converted to run on LNG. LNG is also difficult to transport and store, both on land and on board the ship.

Biofuels

Biofuels are fuels produced from biomass. The advantage of biofuels is that they are sulphur-free and produced from renewable sources. The disadvantage is that some of these fuels have properties that can be problematic for use in marine applications, such as high potential for microbial growth. In addition, biofuels are very expensive. Today, biofuels are mainly used in blends with other fuel types to reduce the overall sulphur content.

Metanol

Methanol is a fuel that can significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions. However, ship engines need to be modified to run on methanol. Maersk, one of the world’s largest shipping companies, plans to launch more than 20 methanol-powered ships between 2024 and 2027 to reduce the climate footprint of its fleet. According to Transport analysis, a major challenge is finding sufficient quantities of sustainably produced methanol.

Ship fuels and alternative propulsion methods under development

Electrification could become an important contribution in the long term, at least for shorter distances. A new type of sailing cargo ship is also under development. Hydrogen and fuel cells are examples of other technologies under development that could reduce the negative impact of shipping on the marine environment.

Scrubber water – a cocktail of different substances

Wash water from scrubbers contains sulphur oxides that acidify the sea, nitrogen oxides that fertilise the sea, and environmentally hazardous substances that can harm plant and animal life, such as heavy metals, PAHs[1] and oil residues. All types of scrubbers cause emissions – but in different volumes and concentrations of substances. Large amounts of contaminated water are discharged from open scrubbers, and although the emission volumes from closed scrubbers are smaller, the wash water still contains higher concentrations of environmentally hazardous substances.

As restrictions on sulphur emissions to air have been tightened, the number of scrubbers on ships has increased significantly – and consequently also the volumes of scrubber water. An estimated 200 million cubic metres[1] of scrubber water was pumped into the Baltic Sea in 2018. By 2020, the permitted sulphur content in marine fuels was reduced from 3.5% m/m (mass per mass) to 0.5%, which is reflected in a clear increase in the number of scrubbers on ships (Fig. 3). The Baltic Sea is a sulphur emission control area (SECA), and stricter sulphur regulations apply here, with a permitted sulphur content of 0.10% by weight in the fuel used on board. One effect of the introduction of scrubber technology is that ships in the Baltic Sea have gone from running on cleaner fuels (such as MGO – see fact box) to running on cheaper and significantly dirtier fuels – together with a scrubber installed. This means that the net inflow of pollutants to the Baltic Sea has increased.

[1] PAHs, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, are found in fossil fuels and oil products, for example. The PAH group consists of several hundred substances and is the largest group of carcinogenic substances known to us today. Source: Swedish Environmental Protection Agency

[2] 200 million cubic metres of washing water is equivalent to approximately 330 Globen arenas filled to the brim with water.

What are the consequences for marine life in the oceans?

Scrubber water is toxic to marine animals even in very low concentrations. Research shows negative effects on crustaceans and mussels, for example, in concentrations as low as a pinch in a cubic metre of water. According to another study, very low concentrations of scrubber water can also cause increased mortality in a common plankton species in the North Sea. The individual PAHs or heavy metals analysed in the study could not explain the high toxicity. Researchers suspect that scrubbers act as ‘witch’s cauldrons’ where unwanted toxic compounds are formed and released into the marine environment.

Research also shows that scrubber water affects the function and structure of the ecosystem – again in very low concentrations. In addition to increased mortality, wash water can also cause reproductive disorders. The study showed that total egg production and hatching rates were negatively affected, which severely impaired the reproductive output of the plankton community. The foraging behaviour of various species in the plankton community was also affected, and when interactions between species change, this has effects on the entire ecosystem. In addition, the researchers conclude that these effects may occur at even lower concentrations than those tested in their study. The substances found in the various studies are also persistent, meaning that they do not break down within a foreseeable time frame and may cause damage to marine life for a long time to come.

Emissions from open scrubbers in territorial waters prohibited – a step in the right direction

From 1 July 2025, ships will be prohibited from discharging scrubber water from open scrubbers in Swedish territorial waters (12 nautical miles from land). However, ships with closed scrubbers may continue to discharge scrubber water in territorial waters until 2029. A majority of ships operating in Swedish waters are equipped with hybrid scrubbers that can be operated in open or closed mode. In practice, this means that ships can switch to closed mode and continue to discharge scrubber water in the territorial zone. In addition, ships will still be able to discharge scrubber water from all types of scrubbers in the economic zone.

Could Sweden have introduced stricter regulations already? And how should economic arguments be weighed against the environmental consequences? We will explore these questions further in our upcoming articles on scrubbers – keep an eye on our website this autumn!