True and false about the industrial fishing in the Baltic Sea

A lot is said about the fishing sector and the fish stocks development in the Baltic Sea, but what is true? Below, BalticWaters tries to respond to common claims in the debate.

“We need more knowledge before we can act”

Despite that several of the Baltic Sea’s important fish species show a dramatic decline, authorities wait to act. The lack of political action is often defended by incomplete knowledge bases, said by both the former Swedish Minister for Rural Affairs Jennie Nilsson and the current Minister for Rural Affairs Anna-Caren Sätherberg.

Contrary to what is often claimed, we have sufficient knowledge to carry out concrete measures for the Baltic Sea´s fish stocks, both nationally and in the EU.

“The bad marine environment – not the fishing – causes the problems in the Baltic Sea”

The decline of Baltic fish species has been going on for decades. In 2008, a review established that fishing was the single most important factor causing the decline of fish stocks. Since then, industrial fishing has taken almost every other spawning/mature herring yearly in the central Baltic Sea during recent years. In the western Baltic Sea, the impact of fishing has been even higher.

The negative impact of fishing on stocks is thus well documented. Overfishing has significantly affected the current situation of herring and cod, and fishing is also the factor we most easily, can regulate as we now must do what we can to restore ecosystems.

“It’s the seal and cormorant that eats up the fish in the Baltic Sea”

That seals and cormorants would be the “basic” problem for the shrinking stocks is not true. In 2017, commercial fishing was estimated to fish up three times as much fish as all birds and seals did together, and the great impact of fishing – rather than seals and cormorants – was confirmed in a study from 2018.

As the large industrial trawlers fished more and got closer to the coast, species such as seals and cormorants have found it difficult to find food. Birds and seals have sought refuge in archipelagos and increased predation pressure on species there, such as pike, salmon, and perch. The increased competition for fish is also noticeable by coastal and recreational fishermen.

BalticWaters is not opposed to increased management of seals and cormorants but believes that the most important thing is to deal with the biggest problem first: industrial fishing. A change in fisheries management is necessary to secure the Baltic Sea ecosystem and biodiversity.

“A move of the trawl boundary hits coastal fishing”

In the Swedish podcast “Baltic Sea Herring Pod”, Anton Paulrud, CEO of the Swedish Pelagic Federation (SPF), says that no boats under 24 meters fish for consumption of fish and that a move of the trawl boundary for these boats would therefore close fish processing plants and eradicate regional fishing. This is not in line with SPF´s own website, nor with the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management´s register. 188 boats fished for herring in 2021, of which 155 boats were under 12 meters. Only 14 boats fishing for herring in the Baltic Sea are over 24 meters, whose catch generally becomes feed.

That a move of the trawl boundary would only hit Swedish fishermen or could not be implemented is also not true, which we went through in Baltic Sea Letter 31.

“Fishing is an important industry”

Commercial fishing is an industry of economic, cultural, and social significance – the Swedish Board of Agriculture 2018

From both a fiscal and socio-economic perspective, large-scale fishing in the Baltic Sea is unprofitable. According to a report by the economist Stefan Fölster, large-scale fishing is estimated to create net costs of SEK 626 million per year through subsidies, administrative costs, and lost tax revenue.

By reducing subsidies alone, society is estimated to be able to gain between SEK 70 and 165 million a year. And in this scenario, Fölster has not put any economic value on a better environment, nor increased tourism and recreation that could result from it.

Today, commercial fishing has a negative effect on the treasury and ecosystems, while it also risks negatively affecting marine tourism. Tourism is the most important of all marine industries and employs over 40,000 people in Sweden. By comparison, the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management estimates that commercial fishing corresponds to about 850 full-time jobs throughout Sweden, of which less than half fish in the Baltic Sea.

“There are plenty of fish in the Baltic Sea”

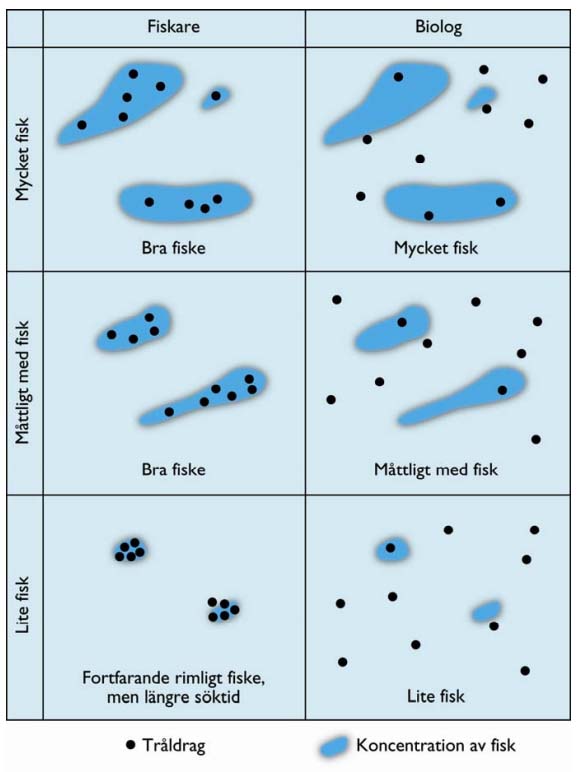

When science and environmental organizations warn of shrinking stocks, fishermen can sometimes argue the opposite. This may be because the fishermen are defending their quotas, or because the different groups are searching for fish in different ways. The commercial fishing actively searches for the fish, usually with an echo sounder, to fish where the largest accumulations of fish are found. The researchers search an area regardless of whether there are fish or not. As a result, researchers may find a relatively low amount of fish in the entire area, while fishermen may find a larger accumulation of fish in a smaller part of the same area. (See picture, where the dark blue areas show where the fish are, and the dots show where the different groups fish. Image source)

A current example concerns the herring in the central Baltic Sea, where representatives of the fishing sector have claimed that they now see a positive development in the stock. The picture is not at all shared by science, which does not see an increase of the historically low herring stock.

Translation of figuretext: Fiskare = Fisherman, Biolog = Biologist , Mycket fisk = A lot of fish, Måttligt med fisk = Moderately with fish, Lite fisk = Some fish, Bra fiske = Good fishing, Fortfarande rimligt fiske, men längre söktid = Still reasonable fishing, but longer search time, Tråldrag = Traw haul, Koncentration av fisk = Fish concentration

“Other countries are fishing out the Baltic Sea”

In 2022, it is estimated that more than 470,000 tonnes of the commercial species will be fished out of the Baltic Sea, which corresponds to more than 46 Eiffel Towers in weight. Sweden and Finland are the countries that fish most herring and salmon.

Distribution of next year´s commercial quotas (herring, sprat, cod (by-catch only) and plaice):

Finland: 24,4 percent

Poland: 18,7 percent

Sweden: 18,3 percent

Latvia: 13,1 percent

Estonia: 12 percent

Denmark: 6,9 percent

Germany: 3,7 percent

Lithuania: 3 percent

“You do not fish for herring during the spawning period”

Industrial forage fishing has been criticized for fishing for herring that accumulated for spawning, or already are spawning. This is denied by Anton Paulrud, CEO of the Swedish Pelagic Federation (SPF), in a podcast by the Baltic Sea Centre. According to Paulrud, no fishing is ongoing in the Baltic Sea during the spawning period. He argues that it can be confirmed by the fact that SLU Aqua’s samples do not contain spawning fish.

However, data from the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management show that 20 percent of the catch (between 2018-2020) is taken up when the fish spawns between April and June and 44 percent is fished between January and March, which is when the fish accumulates for spawning*. SLU Aqua confirms that they have not found spawning fish in their samples, which is natural as the samples are not taken when the fish are spawning.

“The total biomass in the Baltic Sea is constant”

This statement can sometimes flourish in the debate about Baltic herring, with the aim to reassure those concerned about the negative development of herring in the Baltic Sea. It is also used as an argument by fisheries to increase catch quotas, amongst others with claims that increased fishing for sprat would give the herring more room to “grow”.

That is not true. The total biomass of sprat and herring in the Baltic Sea has decreased, and there is no indication that increased fishing for some species, to promote others, would bring more fish into the sea.

“Industrial fishing is a sustainable use of the resource”

Today, over 90 percent of the Swedish catches are used for feed for mink farms and salmon farms.

It is claimed to be a sustainable use of the resource as herring and sprat contain toxins and therefore only should be eaten to a limited extent by humans.

The approach is based on “the fact” that fish is a resource that always should be fished instead of continuing to be part of the marine ecosystem. An important question to consider is whether we should put the ecosystem at risk in the way we do today to create feed for animals that could easily eat food from more sustainable sources.

* Source: Data requested by BalticWaters from the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management.