The herring shortage in northern Sweden is in focus, herring stocks are declining dramatically and the situation in the Gulf of Bothnia will worsen next year if our newly elected politicians do not act immediately. Fully aware of the situation – what are the EU and the Swedish government doing now? In October, ministers will decide on next year’s fisheries. Will our new government defend the ecosystem and coastal fisheries?

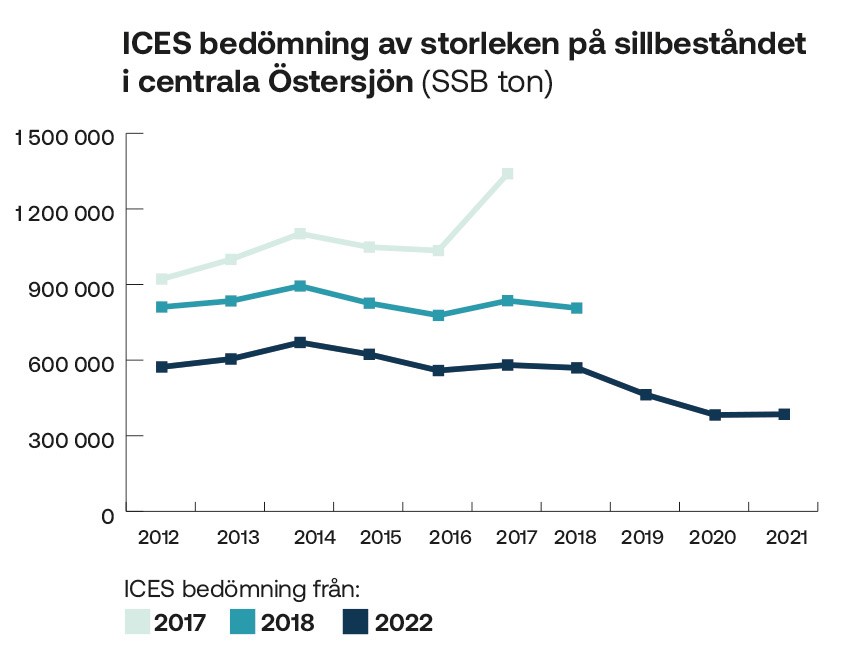

Each year, the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) provides advice for the coming year’s fisheries, which is then used as a basis for politicians to set catch quotas. The scientists’ assessments are based on catch reports from commercial fisheries, as well as test fishing and scientific studies, but the estimates are highly uncertain. BalticWaters has previously reported how ICES in 2017 thought there were 1.34 million tonnes of herring in the central Baltic Sea, but after an update of the models, the estimate was changed to less than 0.6 million tonnes – a miscalculation of over 700 million kg of fish. Similarly, the models overestimated cod in the western Baltic Sea, of which there is now only a remnant after a long period of overfishing.

Risky politics

Uncertainty is part of science, but scientists’ work is also complicated by politics. When recommending next year’s fishing, scientists must use the politically determined Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY) model – a risky tool that sets the fishing quota at the highest possible level a stock can sustain. The theory is that the model should ensure the highest possible harvest of fish without jeopardising growth in future years. However, the risk of a stock being fished down is high, as we have seen in the Baltic Sea.

Even when the stock can be considered collapsed, it is not certain that ICES can propose a fishing ban, as this year’s assessment of western cod is an example. Despite the fact that the stock is at a historically low level and despite uncertainty about the accuracy of the new model, scientists are proposing a catch quota of almost 1000 tonnes, one sixth of the total estimated amount of cod in the western Baltic Sea. The scientists are forced to give the catch, often against their better judgement. Then politicians can still claim to have followed the scientific advice without recognising the risks.

A further problem is the lack of fisheries control. Widespread illegal discards and misreporting of catches make scientists’ work even more difficult and further increase the uncertainty of the models. Again, the EU and politicians recognise this, but fail to act.

Critical situation in the Gulf of Bothnia – time to stop fishing?

To adapt fisheries to the scientific uncertainty, the Baltic Sea Centre has proposed halving the fishing effort compared to the MSY advice, but the question is whether this is already too late given the status of stocks in the Baltic Sea.

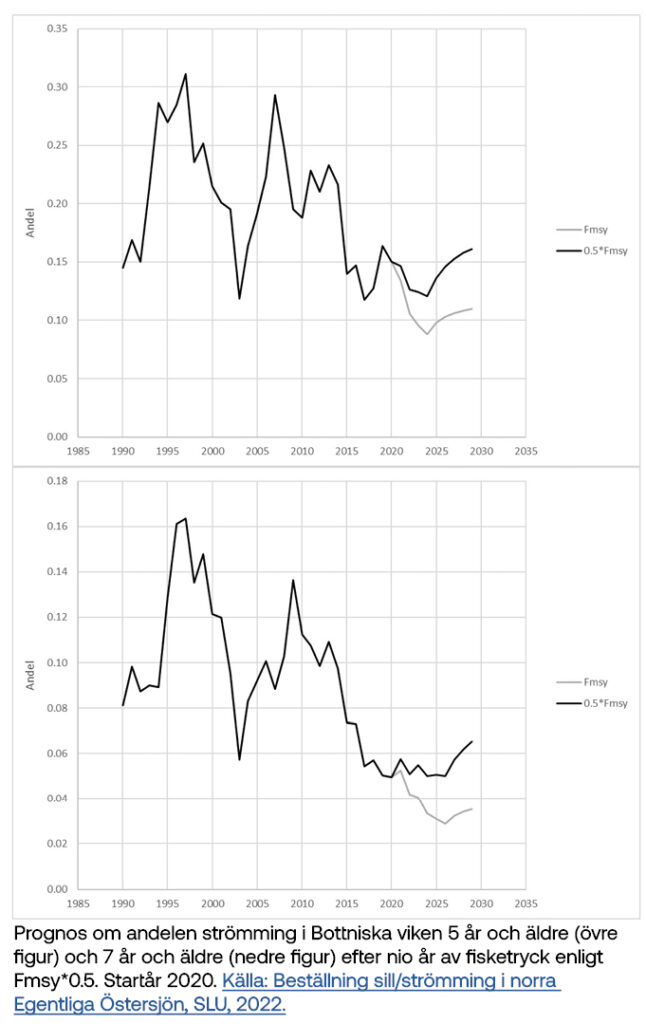

In the Gulf of Bothnia, halving fishing pressure will not help to quickly save coastal fisheries or secure the stock, according to a forecast from SLU Aqua.

The report shows that large herring, which are vital to both coastal fisheries and the ecosystem, will continue to decline rapidly if fishing pressure is maintained at current levels (grey line). A halving of fishing pressure (black line) would mean that the situation in the coming years would remain at the disastrous level we have seen this year. If the stock is to recover, fishing will probably have to stop completely.

However, the European Commission’s proposal for next year is much higher than a halved fishing pressure. Next year’s fishing is proposed at 80 000 tonnes, which is 30 000 tonnes above the level of a halved fishing pressure. This year’s surströmming shortage, closed factories and coastal fishermen closing down could be the beginning of the end for a long culturally important fishing tradition and for a fish that is crucial to the Baltic Sea ecosystem.

Figure: Forecast of the proportion of herring in the Gulf of Bothnia 5 years and older (upper figure) and 7 years and older (lower figure) after nine years of fishing pressure according to Fmsy*0.5. Starting year 2020. Source: SLU, 2022.

Quotas for next year’s fisheries are set – what is the government doing?

Today, a few fishmeal fishermen earn millions from continued fishing, while society loses hundreds of millions every year. Despite this, politicians’ high-risk approach to the Baltic Sea ecosystem continues, which the new government must change.

Parliament, scientists and organisations can raise the issue and ask for change, but the power lies with the government. Our new Minister for Agriculture, whoever he or she is, must take into account the scientific uncertainty surrounding the quotas and ensure that they are set with significant safety margins. This will require intensive work with our own authorities, the EU and other countries in the region. Read what the new government needs to do here (in swedish).

Many thanks to everyone who donated to the ReCod project – stocking of small cod in the Baltic Sea!

In total, ReCod has received SEK 130,000, which has enabled another release of cod larvae in Tvären. Want to know what happened in the project this season? Read the article An intense and successful year for ReCod here.

The Baltic Sea Brief is published by BalticWaters and sent to politicians, journalists, opinion leaders and the interested public.

For further information visit balticwaters.org.