Politicians in parliament and government are helpless in the face of the Baltic Sea’s declining fish stocks, a crisis that means, among other things, that no environmental objectives for the sea can be achieved. With Swedish respect for authorities, the politicians put their trust in a management system that contains risks and uncertainties at many different levels. We wonder if the same reckless risk assessments would be allowed in other sectors?

The overarching problem is how fishing quotas are set today – the so-called “quota process”. Every step in the quota process is associated with uncertainties. If the risks are incorrectly estimated, and thus the safety margin is too small, the consequences can be disastrous – for example, overfishing that causes stocks to decline and eventually collapse. The price of mismanaged risks is paid by the Baltic Sea environment and ecology.

Risks of the quota process

The scientific models are flawed

The International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) makes recommendations to the Commission and the Council of Ministers, based on models where estimates are uncertain and important data are not always taken into account:

- Fish stocks are part of a complex food web, but quotas are set separately – species by species – without taking interactions into account.

- Nor do the recommendations take into account that a stock may consist of several different populations, such as herring, where each population has its own unique genetic variations.

- Another major problem is that the only criteria considered in the recommendations are the amount of spawning fish and fish mortality. The recommendations do not include size and age composition. In the Baltic Sea, changes have been observed for both cod and herring where the large, older fish are disappearing and the stocks consist of younger and smaller individuals that have a slower growth rate and that reach spawning maturity earlier.

Scientific modelling needs to be developed to better describe the different fish populations in the Baltic Sea.

Misreporting of catches has far-reaching consequences

In the data used in the scientific models the reported catches of fishermen play a major role. It has proved difficult to estimate the different species if they consist of herring or sprat, which can create an incentive for fishermen to over-report species for which they have an available quota. In her 2007 book “Silent Sea”, Isabella Lövin describes how data is processed and modified by forces that she describes as industrial, socio-economic and political, in order to enable increased quotas.

While misreporting and fraudulent landings are well documented, there is a lack of control and the fines are very low, as we showed in our report “Errors and fraud in fishing – a threat to the Baltic Sea”.

Misreporting, cheating, and modified data create uncertainty that can lead to inaccurate stock estimates.

Sustainable fisheries are a small part of policy makers’ focus

For the ministers who meet in Brussels for annual negotiations, fisheries are only a small part of their responsibilities, and they are often seen as not being sufficiently familiar with the issue of quota process. In addition to safeguarding environmentally sustainable fisheries, they also have to balance business and social objectives. Furthermore, politicians might be subject to other pressures, in Sweden primarily from large-scale fishermen who own individual fishing rights, known as individual transferable fishing rights (ITQs).

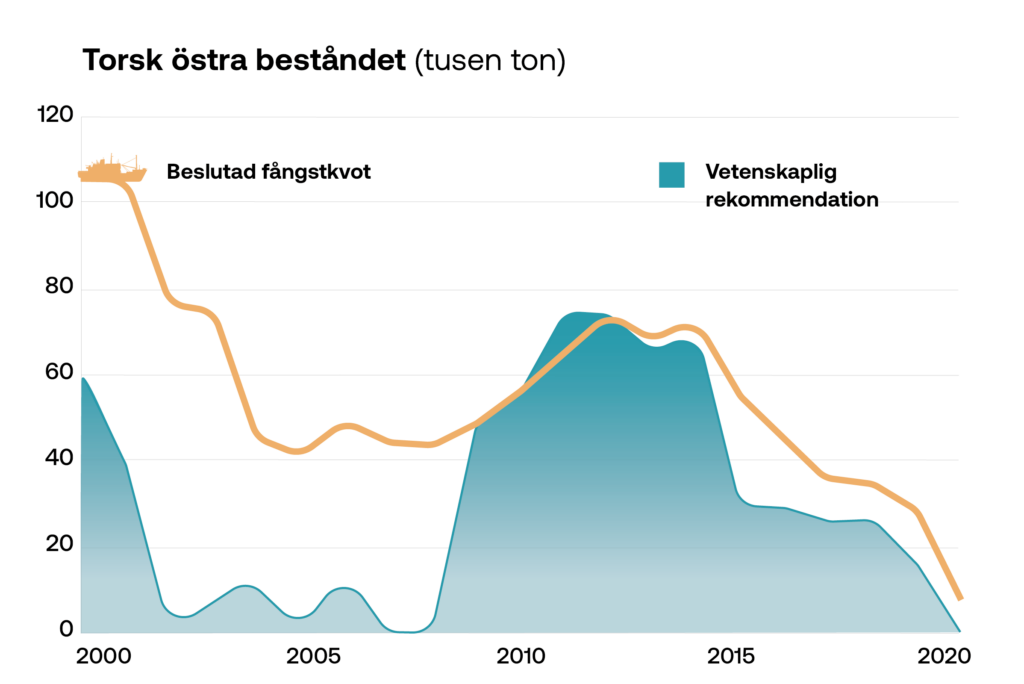

Decision-makers focusing on objectives other than environmental ones, combined with pressure from fisheries, create a risk that quotas might be set above the scientific recommendations. This is usually the outcome of the quota negotiations for the Baltic Sea, where a majority of the fishing quotas, for example for cod in the Baltic Sea, have been set above ICES’ already risky recommendations over the past 20 years.

“Torsk östra beståndet (tusen ton)” = “Eastern cod stock (thousand tonnes)”, ”Beslutad fångstkvot” = ”Decided catch quota”, ”Vetenskaplig rekommendation” = Scientific recommendation”

Ministers are pushed to ignore science and prioritize the profits of the fishing industry over the environment.

Management model depletes fish stocks in the Baltic Sea

Maximum sustainable yield (MSY) is the principle on which the quota process is based. The European Fisheries Policy describes MSY as “the theoretically highest balanced average yield that can be continuously taken from a stock under average environmental conditions without significantly affecting the reproductive process”. In practice, MSY means that fishing is conducted at the level at which the stock yields the highest possible return, as close to the maximum limit as possible, before science judges that the stock is at risk of collapse.

MSY is criticised by the scientific community, including, remarkably, by one of its authors, Sidney Holt, who dismisses MSY as a good management target. He described fishing under MSY as “irrational folly” and argued that limiting fishing to below maximum sustainable yield would increase both the profitability of the fishing industry and the resilience of fish stocks and ecosystems.

MSY is not working as a principle for Baltic Sea fish stocks – the system needs to be reformed.

A more detailed summary of the risks surrounding the quota process can be found here.

Management must change

The quota process is thus filled with such great uncertainties that the risks of making decisions that permanently threaten the fish stocks of the Baltic Sea are very high. The Baltic cod is a telling example. There is a precautionary principle in the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP), but this is only used when ICES considers the data to be highly uncertain, and only to adjust quotas marginally.

With such large risks at several levels in the quota process, a radically different approach to how quotas should be set is required, and this has been expressed by both researchers and authorities:

SwAM proposes that the lack of knowledge about age distribution means that the quota for herring should be set at about 70 per cent of MSY. For a detailed explanation, see HaV 2022-03-31 Dnr 1:2021.

The Baltic Sea Centre at Stockholm University proposes to set the quotas at 50% of MSY. Given all the risks associated with the current quota process, which are not taken into account in the decisions on how much can be fished, it is highly likely that the quotas have been set much higher than everyone intended. This is clearly reflected in the size of the Baltic Sea’s most valuable fish populations and in the development of the number of spawning fish.

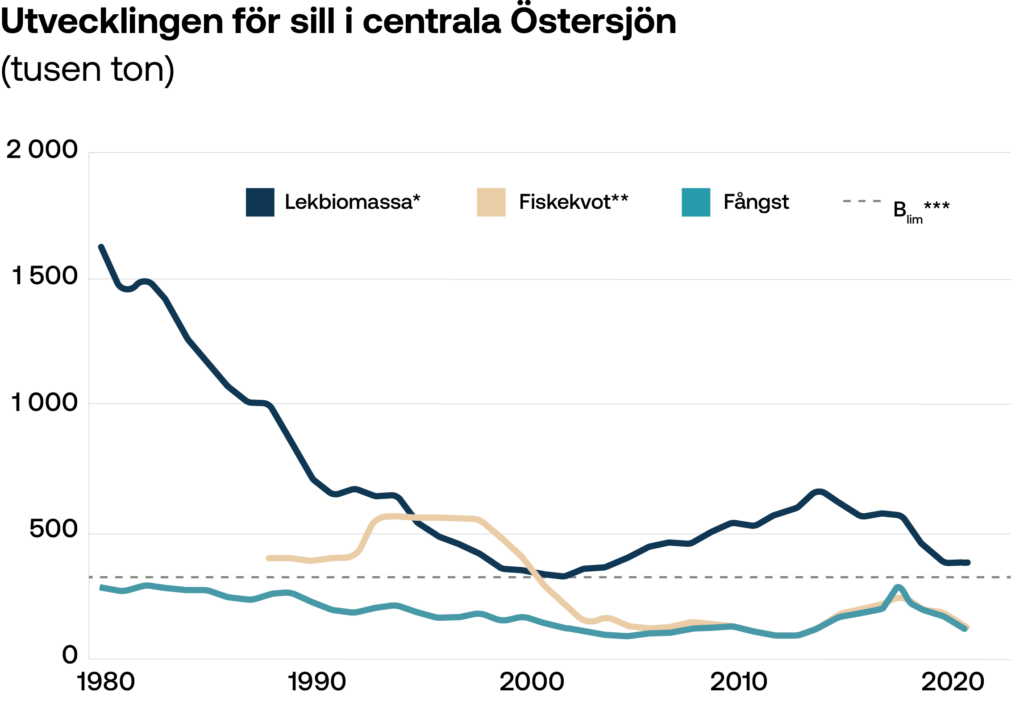

“Utveckling för sill i centrala Östersjön (tusen ton)” = “Development of the central Baltic Sea herring (thousand tonnes)”, “Lekbiomassa*” = “Spawning biomass*”, “Fiskekvot**” = “Fishing quota**”, “Fångst” = “Catch”

* The part of the stock that has reached sexual maturity.

** ICES reports historical quotas (TACs) from the late 1980s.

*** Reference value when spawning biomass is so low that reproduction is threatened, which should lead to further reductions in quotas or closures (ICES).

In the central Baltic Sea, herring stocks have declined by more than 80 per cent compared to the 1970s. In the last four years, the stock has declined by 40 per cent and is now at a critical level. Scientists and coastal fishermen report that there is a shortage of large herring for human consumption. Today, industrial fishing accounts for more than 90 per cent of the Swedish catch of herring – catches that are processed into fishmeal for salmon farms, mink and chicken feed.

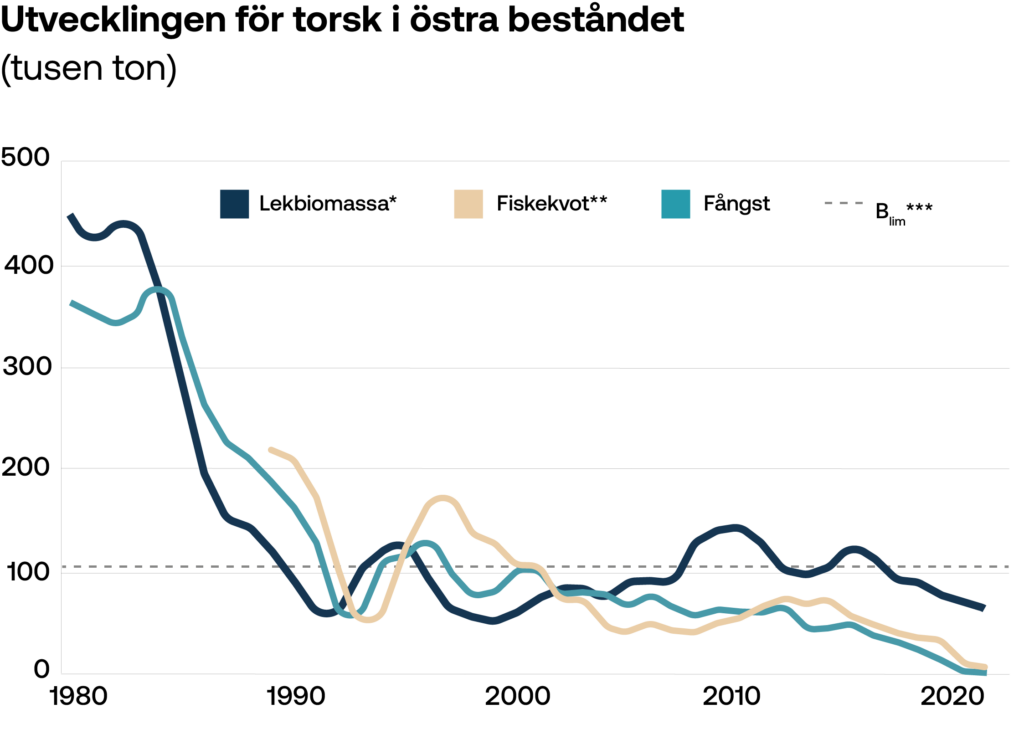

“Utvecklingen för torsk i östra beståndet (tusen ton)” = Development of the eastern cod stock (thousand tonnes), “Lekbiomassa*” = “Spawning biomass*”, “Fiskekvot**” = “Fishing quota**”, “Fångst” = “Catch“

* The part of the stock that has reached sexual maturity.

** ICES reports historical quotas (TACs) from the late 1980s.

*** Reference value when spawning biomass is so low that reproduction is threatened, which should lead to further reductions in quotas or closures (ICES).

Since 2019, there has been a ban on cod fishing in the large eastern stock of the Baltic Sea. In the smaller western stock, cod fishing continues, even though the stock is very weak.

At the end of May, ICES will issue recommendations for the 2024 fishery. Swedish politicians and officials must already signal that the starting point for next year’s quotas must be to take the risks into account and set quotas that are considerably lower than before. Peter Kullgren is the first rural affairs minister in many decades who does not come from the Social Democrats or the Centre Party. Will he be the first to make a difference for the endangered fish populations of the Baltic Sea?