Coastal fishermen and managers have long argued that the large-scale exploitation of Baltic herring by industrial trawlers may force species such as grey seals and cormorants to move closer to the coast in search of food. Yet the issue has not been scientifically investigated. Now, in a project funded by BalticWaters, Agnes Olin will investigate the link between large-scale fishing and the hunting behaviour of grey seals and how it affects the Baltic Sea’s coastal ecosystem.

In recent years, fishermen have reported that more and more grey seals and cormorants have moved further into the archipelago. There are many stories of fishing nets being gutted by seals and this development has caused great despair among coastal fishermen. If seals and cormorants eat more of the coast’s predatory fish, there is a risk that the entire coastal ecosystem will be affected – for example, the amount of filamentous algae may increase, which will exacerbate the symptoms of eutrophication.

Coastal fishermen, managers and scientists have long argued that it is the large-scale industrial trawling for herring that has driven seals, and perhaps even cormorants, further into the archipelago. Herring is an important food, especially for seals, and there are no longer enough large herring in the open sea. Despite the topicality of the issue, the link has not yet been scientifically investigated.

– Much of what we know is based on anecdotal observations along the coast. While these observations are incredibly valuable, it is important to also investigate the issue scientifically, says Agnes Olin, researcher at the Department of Aquatic Resources at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences.

Agnes is leading a project funded by BalticWaters to investigate whether the increased presence of grey seals and cormorants in the inner archipelago is due to the lack of large herring – but also how the coastal ecosystem is affected by such a possible change.

Large-scale herring fishing can have long-range effects on coastal ecosystems

The first part of the project involves mapping the movement patterns of grey seals and cormorants, and then investigating whether they can be linked to changes in herring stocks, or whether other factors such as hunting could be behind the shift towards the coast.

– It will be difficult to arrive at a definitive answer, but we will be able to see which explanatory models are supported by the data and possibly rule out some explanations, Agnes explains.

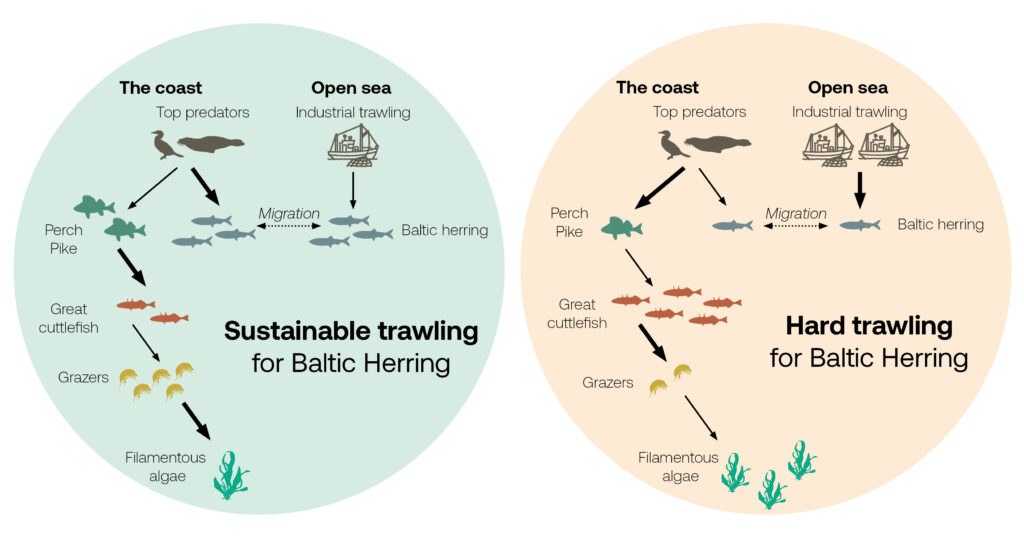

In the next step, Agnes will investigate how these changes affect coastal ecosystems and the marine environment. The project hypothesises that large-scale trawling for herring triggers a so-called trophic cascade – an ecological chain effect that occurs when changes at one level of the food web cause changes at other levels, meaning that the heavy herring fishing at sea could have long-lasting effects on the entire coastal ecosystem.

– We suspect that the lack of large herring leads to coastal predatory fish such as perch and pike decreasing in numbers as they become food for seals and cormorants. This in turn leads to an increase in prey for the predatory fish, especially big spadefish, resulting in a decrease in their prey – small grazers such as marbled crayfish, Agnes explains.

The grazers play an important role in the coastal ecosystem by keeping down the amount of filamentous algae that otherwise degrades habitat and water quality and contributes to exacerbating the symptoms of eutrophication.

Illustration of the project’s hypotheses on the effects of large-scale and sustainable trawling for Baltic herring on the Baltic Sea ecosystem. Solid lines show extraction or consumption, while dashed lines show migration. The thicker the line, the greater the extent.

There is research showing such a trophic cascade in the Baltic coastal ecosystem, but no one has previously linked the whole chain and investigated the connection with trawling, says Agnes.

– Using the same logic, it is assumed that sustainable trawling for Baltic herring would have the opposite effect. More Baltic herring in the Baltic Sea’s offshore would mean that top predators that have herring as their main food do not have to seek out coastal areas. A reduced pressure on coastal predatory fish will ultimately lead to stocks of large spike and thread algae being kept down.

A broader perspective can pave the way for new management measures

Previous research has primarily looked at the impact of grey seals and cormorants on fisheries and their income. This project turns that around and instead looks at how fishing affects the Baltic Sea ecosystem. By putting seals and cormorants into a wider ecosystem perspective, Agnes hopes that the study can help broaden the view of what types of management measures are needed.

– Many people are already thinking along these lines, but the debate is often too narrow and misses the entire chain of causes. Seals and cormorants are a real problem for many coastal fishermen, but the risk is that it becomes something that is easy to blame, says Agnes.

The fact that coastal fishermen experience major problems with seals and cormorants has made the management of these species a subject of intense and often emotional debate. Agnes believes that the strong reactions to the subject could be one reason why the issues have not been studied before and why some researchers have avoided the issue.

Grey seals and cormorants.

– I think there is a risk of being perceived as downplaying the impact of seals and cormorants on coastal fisheries when other causes are emphasised. That’s a misunderstanding, because what you’re doing is trying to understand the root causes, she says.

For management measures to have the desired effect, it is crucial that they are based on science – this study fills an important gap.

The project is expected to provide valuable information on how the management of Baltic herring fisheries should be designed to minimise negative impacts not only on the herring stock but also on the rest of the ecosystem, including eutrophication symptoms in the coastal zone.

– Among other things, the results may provide guidance on how much can be fished, where it can be fished and what size regulations are required, Agnes explains.

More about the project

The project will be carried out at the Department of Aquatic Resources, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences and will run until 2026. Through BalticWater’s Program to fund research projects and pre-studies, the project has been granted funding of SEK 974,899 to support the implementation of the scientific study. You can read more about the five other projects that have received funding in the article Six new research projects for a living Baltic Sea.