The capacity of forests to store carbon is well recognised. However, it’s less known that sedimentary seabeds in the Baltic Sea can serve as significant carbon sinks. At the same time, bottom trawling – a fishing method that has been compared to clear-cutting – can reduce carbon storage by stirring up and displacing sediment. In a new project funded by BalticWaters, Clare Bradshaw and her colleagues at Stockholm University will investigate the effects of bottom trawling on carbon storage in the Baltic Sea.

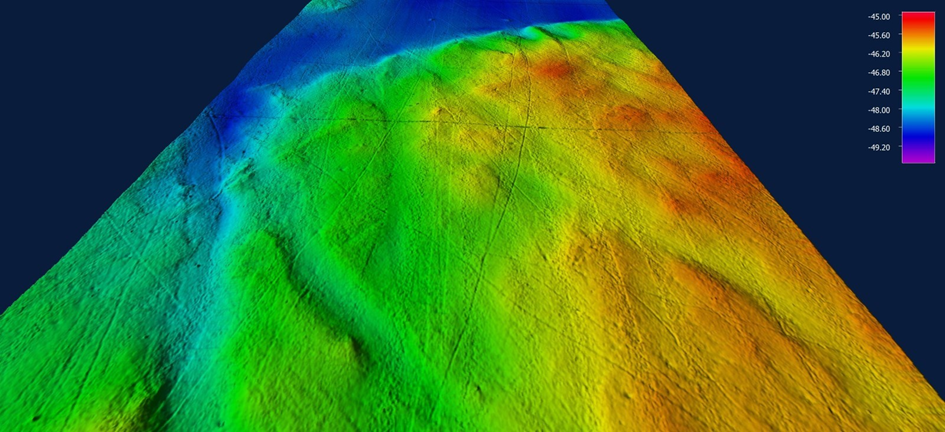

Trawl tracks on the seabed in the southern Baltic Sea. Image taken with multibeam technology. Each track is about two metres wide. Photo: Martin Jakobsson

On parts of the Baltic Sea seabed, clear furrows are visible. These are the permanent tracks of heavy trawl doors that have been dragged back and forth over the sediments for years. It is not a secret that bottom trawling imposes considerable disturbances on the marine environment, both through large catches of fish and physical damage to the seabed.

– Many people only see a muddy seabed, but these sediments are full of life. Here, a myriad of crucial chemical processes unfold, that are crucial to the ecosystem and its functions, says Clare Bradshaw.

Clare, Professor at the Department of Ecology, Environment and Plant Sciences at Stockholm University, has devoted much of her research to studying disturbances on the seabed. This autumn she will lead a new project to investigate how bottom trawling affects carbon cycling in the Baltic Sea.

– We need to understand how bottom trawling affects the carbon stored in the sediments. Models and calculations suggest significant effects, but there are currently no measurements of how much carbon is released and where it actually goes, says Clare.

Clare Bradshaw. Photo: Private

Experimental trawling outside of Askö

Clare and her research team will conduct a field experiment near the Askö laboratory field station in the Trosa archipelago. An industrial trawler will be hired to lay a 1 km long track at a depth of 25-30 metres. The researchers will measure both the spatial and temporal distribution of carbon, especially in the form of methane. They will also carry out measurements to monitor how the sediment is dispersed and how this affects the level of carbon in the water.

– During the actual trawling, there is a lot to be done at once. We will immediately conduct an acoustic assessment to measure both the dimensions of the track and the movement of sediment. At the same time, we will also measure the methane concentrations all the way from the bottom to the surface, Clare explains.

Once the first measurements are completed, the researchers will be able to rest, at least fora while. During the following week, the measurements will be repeated a number of times at different intervals – which also brings its own challenges.

– The sediment cloud, which contains both suspended particles and dissolved substances, starts off tall and narrow, gradually settling and expanding over time. The cloud will drift with the ocean currents, which can make it difficult to find again after a few days, she says.

What is blue carbon?

Blue carbon refers to the carbon sequestered from the atmosphere and water and stored within coastal and marine ecosystems. . In the Baltic Sea, carbon uptake occurs predominantly within vegetation like eelgrass and bladderwrack. However, the most significant carbon reservoir lies within the seabed, where organic matter can be buried for thousands of years through continous sedimentation. The Baltic Sea’s capacity for carbon sequestration is decreasing due to factors such as eutrophication, overfishing and other human disturbances. Beyond diminishing carbon storage, the sea’s deteriorating environmental condition also raises concerns about heightened methane emissions.

More information on blue carbon in coastal areas and practical recommendations for action can be found in BalticWater’s policy document: Help the Baltic Sea to mitigate climate change.

A day in the field on the research vessel R/V Electra during a previous project. The researchers take sediment samples in a trawled area. In the picture: Martin Jakobsson (Stockholm University), Thomas Strömsnäs (captain of Electra), Benedetta Esposito (research assistant). Photo: Clare Bradshaw

Bottom trawling in the Baltic Sea

The project will be the first of its kind in the Baltic Sea. Previous studies have used modelling and are based on several uncertain assumptions. To understand carbon storage in the Baltic Sea, the effect needs to be studied on-site.

– The Baltic Sea is very different from other seas. The bottom sediments contain a unique set of animals and organisms, which have a major impact on how carbon is sequestered. It is also a particularly cold and shallow sea, which also affects both biological and chemical processes relevant to carbon cycling, Clare explains.

Currently, bottom trawling is not a problem in the Baltic Sea. In the largest fishing area in the southern Baltic Sea, the fishing method has not been allowed since 2019 when the cod stocks collapsed.

Despite this, Clare says the study is important for the future management of the Baltic Sea. The decision to authorise or ban trawling is taken year by year and it is likely that the issue of reintroducing the fishing method will be raised again.

– Perhaps the cod will rebound or there will be a wish to trawl for other species. When that happens, it’s important that we can say more about how bottom trawling affects carbon cycling, she continues.

Bottom trawling in the vulnerable environment of the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea, a shallow, species-poor sea with slow water exchange, is considered particularly vulnerable to human disturbance. Decades of overfishing, coupled with other disturbances such as eutrophication and pollution, have resulted in the depletion of numerous fish stocks and pose a threat to many more. Trawling activities in the Baltic Sea not only contribute to continued overfishing, but also cause substantial physical damage by stirring up sediments and destroying habitats – which can affect the entire marine ecosystem and its functions.

A picture of a trawl door on a trawler in Simrishamn – a solid metal frame used to keep the trawl net open and close to the seabed as it is pulled forward. The door is 3 metres wide and 2 metres high. Photo: Clare Bradshaw

Climate mitigation requires more accurate estimates of blue carbon

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in protecting and restoring ecosystems that naturally sequester a lot of carbon, as a climate measure. The focus has mainly been on carbon storage in forests and soils. At present, the ocean is not included in the reporting of Sweden’s greenhouse gas emissions and uptake, which may explain the lack of measures targeting blue carbon ecosystems.

Clare on board the research vessel with a sediment sampler – a so-called “Gemini corer”. *Photo: Clare Bradshaw

– It is obvious that we need to look everywhere and not just at what is happening on land. The ocean covers roughly 70% of the Earth’s surface and plays a crucial role in natural carbon storage, says Clare.

Despite the need to account for blue carbon, Clare says that we currently need more knowledge to make reliable calculations. For this to be possible, more research is needed in the first place.

– If we would base climate measures on current knowledge of blue carbon, there’s a considerable risk of inaccuracies. The carbon storage might be either underestimated or overestimated, which could lead to ineffective measures, she concludes.

More about the project

The project “Does bottom trawling affect blue carbon storage in the Baltic Sea?” will be carried out by the Department of Ecology, Environment and Plant Sciences, Stockholm University, and will run until 2025. Through BalticWater’s Program for smaller research projects and pre-studies, the project has been granted funding of SEK 578 880 to support the implementation of the scientific study. You can read more about the five other projects that have received funding in the article Six new research projects for a living Baltic Sea.