In what types of environments does zooplankton thrive? This is what Amanda Jansson, who has just completed a bachelor’s degree in microbiology at Uppsala University, has taken a closer look at in their thesis conducted within the framework of the project ReCod – release of small cod in the Baltic Sea. Amanda hopes that their work will contribute with information on the most optimal locations for releasing, for example, cod larvae.

– Looking through the microscope is like peering into another world. It’s incredibly fascinating, says Amanda, who hopes to continue researching zooplankton, a crucial component of the marine food web.

The bays that Amanda has included in her research are Baggenfjärden in the inner archipelago of Stockholm, Tvären off the coast of Södermanland, and Kappelshamnsvik on the northwest coast of Gotland – the same bays where the ReCod project releases cod larvae.

– It feels relevant to know which waters you are releasing larvae into. Bays and coastal areas are also places where many fish have their spawning, egg-laying, and mating grounds. The characteristics of the bays and the condition of the water in the bay have a significant impact on the fish, says Amanda.

Amanda Jansson. Private photo.

The purpose of Amanda’s thesis was to determine how the three bays differ in terms of zooplankton composition.

“Coastal areas are regions with high variation in inflow, runoff, depth, and wind impact. This results in significant structural differences between two locations close to each other. Despite this, coastal areas are not closely examined, and homogeneity in plankton composition is assumed, even though it may not be accurate,” writes Amanda in the popular science summary.

Why is it assumed that there is homogeneity in plankton composition in different bays?

– Partly, I think within large-scale plankton research, there is not a strong focus on what is happening in each bay. Researchers are more interested in the overall picture, but this approach carries the risk of being misleading. Additionally, I believe that this type of research, and Baltic Sea research in general, is not very popular, and there is a lack of funding – you can’t go around taking samples everywhere.

Why did you become interested in zooplankton?

– I’ve always found the ocean fascinating, and as I studied biology and marine biology, the role of zooplankton and phytoplankton became clearer and more significant to me. I realized how crucial they are.

Amanda’s results show a clear difference in zooplankton composition and quantity among the three bays. There are also minor differences between individual samples from the same bay. Tvären and Baggenfjärden were dominated by the zooplankton species rotifers, while Kappelshamnsviken was dominated by copepods.

– Baggenfjärden and Tvären are somewhat more similar to each other.

The most favorable bay for zooplankton life is Kappelshamnsviken.

– They prefer deeper waters with higher salinity. Ideally, there should also not be much eutrophication, says Amanda.

Kappelshamnsviken has the most marine environment among the examined bays. It also exhibits the greatest variations in depth and temperature, and it has an abundance of zooplankton, which benefits several different species.

– What we see in the Baltic Sea right now is a kind of shift in structure from having large quantities of zooplankton to more cyanobacteria. Cyanobacteria, and rotifers that eat cyanobacteria, dominate. It is often described as a problem because zooplankton eat what is available and what they can catch, but they can harm their mouthparts if they consume cyanobacteria. The eutrophication issues we have in the Baltic Sea threaten all these species.

Amanda used samples taken last year on Gotland and samples from this summer from the other two bays. The samples are taken as “whole column drags,” meaning a sample is taken from the sea floor to the water surface to represent the entire water column. The samples are then analyzed’

– I spent a month trying not to get a stiff neck while looking at these tiny creatures, laughs Amanda.

Analysis of samples is time-consuming, meticulous work.

– Analyzing one sample takes about 8–10 hours. There is a lot of plankton in one sample. I only looked at a fraction of the sample, but there is still a hundred zooplankton in a small bowl. These are then counted, identified by species and age, and preferably also sexed.

How representative is your thesis for bays in the Baltic Sea?

– It is representative for these three bays during this period. Plankton, like many other things in nature, exists in larger or smaller quantities depending on the season and how the year has been. But my results should give a small indication of what it looks like in bays during the summer.

Above all, Amanda’s work will be highly relevant for the release of cod larvae done within the ReCod project, as it is important to ensure that there is food for the cod larvae in the bays where they are released.

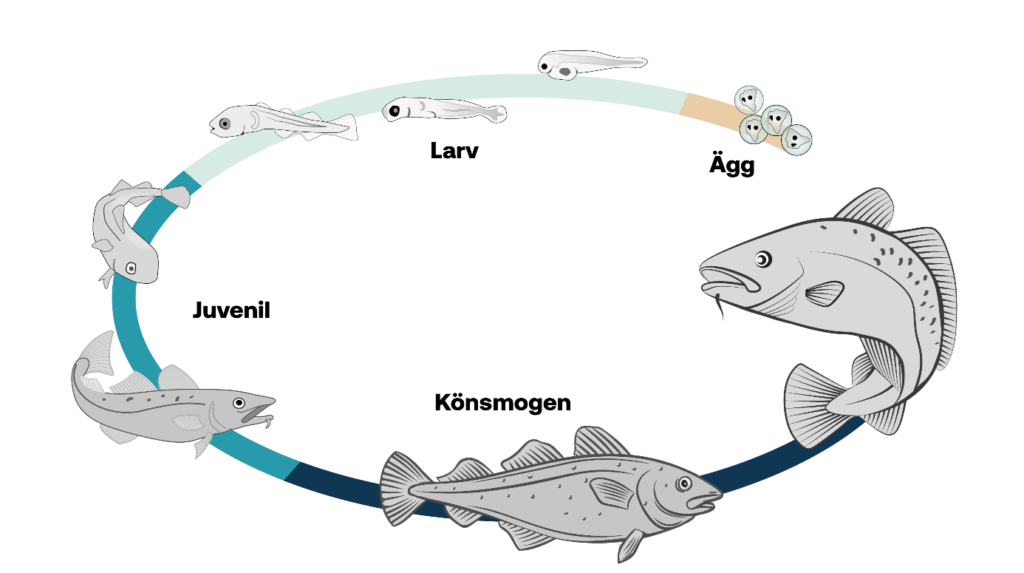

– Cod larvae have a yolk sac filled with nutrients at their stomach when they hatch from their egg. The larva lives its first days on the nutrients from the yolk sac as it does not yet have a fully developed jaw and limited swimming ability. 4-6 days after hatching, the larva has a functional jaw and can move better in the water – the larva is ready to start hunting and eating plankton. That’s exactly when we release the larva into the bay so it can have its first meal in the Baltic Sea, says Johanna Fröjd, project manager for ReCod.

Life stages of cod. Illustration: Sofie Handberg

To scientifically evaluate the ReCod project, it is important to understand what happens to the larvae after their release.

– We evaluate the project using test fishing, and if, for example, we fail to recapture any small cod that can be traced back to the project, we need to understand why. With Amanda’s study, we can determine if there was food available for the larvae during the time of the releases and what kind of food it was. In other words, we can assess if the bay’s environment was favorable for the larvae to survive and develop into fish.

Amanda Jansson, what should be done for future research?

– Personally, I would find it very interesting to test and see what happens if the same study is conducted in northern Sweden, Finland, and Estonia. Would we get similar results? It would also be exciting to explore the interactions between cyanobacteria and zooplankton.

What has fascinated you during your work?

– How challenging it can be to identify the species – it can be very difficult. There is individual variation within species as well. They have slightly different colorations, different patterns, says Amanda.

Amanda has now started a master’s degree in aquatic ecology at Uppsala University.

– It feels super exciting to dive even deeper into this and immerse myself in all of this, concludes Amanda.

About ReCod

The project is carried out at the research station Ar on Gotland – in the middle of the Baltic Sea. The goal of ReCod is to conduct experiments with the release of 4–6-day-old cod larvae at several locations along the east coast to investigate whether the larvae survive and successfully establish themselves. If the experiments are successful, there is the possibility of reintroducing cod in the Baltic Sea at more locations, thereby increasing the chances of preserving and protecting the unique eastern stock. ReCod is implemented and financed by BalticWaters and Uppsala University. In addition, several partners contribute to the project in various ways: Leader Gute, Region Gotland, the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, and the Ulla and Curt Nicolin Foundation. A total of over 50 million SEK is invested in the project.

Would you like to know more? Visit the project’s website.