Herring fishing should have been cut by over 60 per cent – yet quotas were set high

In mid-October, the 2023 fishing quotas for the Baltic Sea were set. The decision was a disappointment for those who had hoped for an improvement in fish stocks and a turnaround in the disastrous situation for herring in the Baltic Sea. On the positive side is the big difference in the debate leading up to the decision. Finally, the right issues are being discussed – and now there are hard facts about how management must change.

Photo: Tobias Dahlin/azotelibrary.com

Recently, the media has reported extensively on the risks of intensive industrial fishing and the need to reduce quotas. The effects on the Baltic Sea’s ecosystem and coastal fishing have had a major impact and knowledge has increased significantly among the public, journalists, and politicians. While the quotas were barely mentioned in previous years, the reporting for this year’s decision has clearly highlighted the shortcomings in the scientific data and the lack of larger and older individuals in the various herring populations.

In the central Baltic Sea, the ministers decided on a quota increase of 32 per cent for herring – despite the catastrophic situation we have seen along the entire Swedish coast. The quota increase was based on the estimate of a single strong year class – an estimate that the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) itself says is uncertain. In 2020, the year class appeared to be strong, which was not the case in the 2021 analysis. Despite the risk of ecosystem effects, the suffering of coastal fisheries and uncertain scientific data, a unanimous group of ministers decided on a substantial quota increase next year.

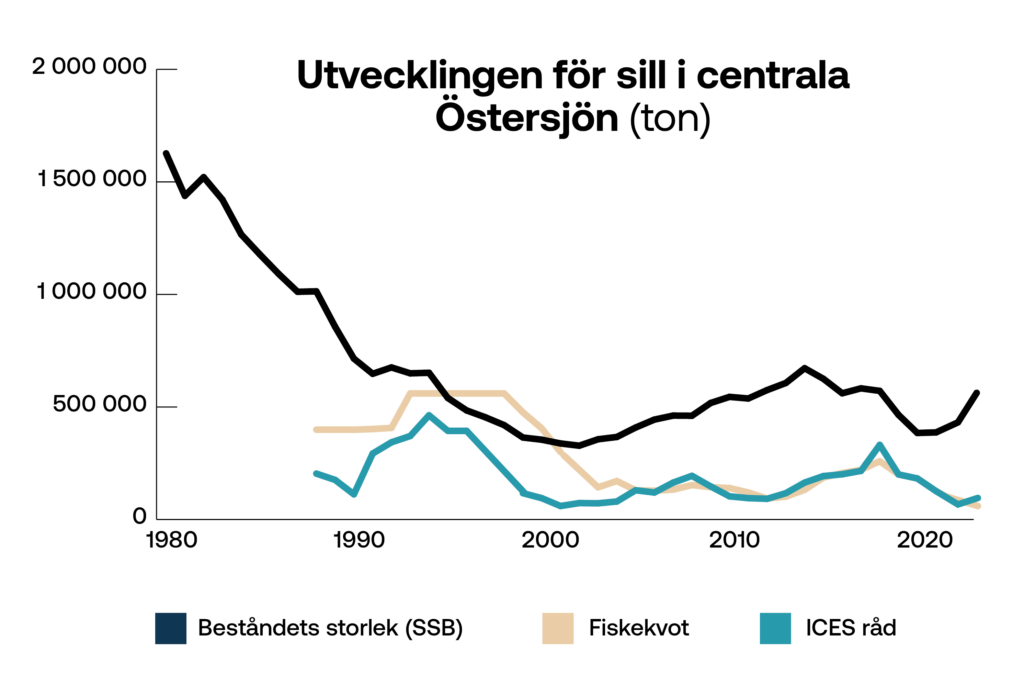

Graph: Historically, ministers have often set quotas above scientific advice, and sometimes above the size of the stock. Ministers’ decisions have been close to ICES advice since the mid-2000s, yet the stock is in crisis. These developments have put the spotlight on the political governance of the scientific councils, but also on the uncertainties of the scientific evidence. The increase in the stock seen in 2023 is based on data from a single strong year class – an assessment that ICES itself says is uncertain.

Utvecklingen för sill i centrala Östersjön = Development of herring in the central Baltic Sea, Beståndets storlet (SSB) = Size of the stock (SSB), Fiskekvot = Fishing quota, ICES råd = ICES advice

What should the quotas be?

Recently, important knowledge from scientists has emerged, with concrete figures on what a more sustainable fishery would mean. SLU Aqua has shown that catches must be reduced by at least 60-80 per cent in the Gulf of Bothnia over decades to maintain a good age and size structure in the herring stock. The data was delivered to the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management one month before the quota decisions were made, yet the ministers decided on a fishery of 80,000 tonnes for 2023 – ten thousand tonnes more than what was fished in the area last year.

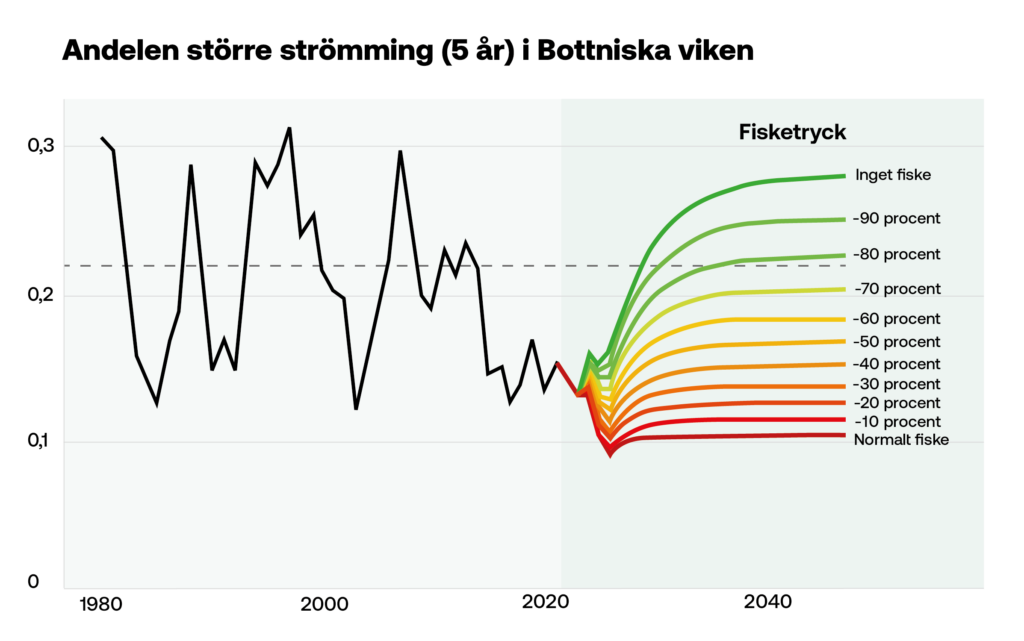

According to SLU Aqua, a 20 per cent reduction in fish withdrawals, known as fishing pressure, would mean a continued strong decline for the larger herring. A lower fishing pressure is needed to bring back the important larger herring – illustrated by the green lines in the graph below.

Graph: The figure shows the proportion of larger herring (5 years and older) in the Gulf of Bothnia depending on fishing pressure. For 2023, a “normal” fishing pressure is 100,000 tonnes, which means that it is in line with the current scientific advice and what politicians usually decide (FMSY).According to SLU Aqua, the fishing pressure should be a maximum of 20,000 – 40,000 tonnes in 2023 (corresponding to -60 to -80 percent, yellow and green lines). The dotted line in the graph is the average size for the period until now.

Although not modelled for sprat or herring in the central Baltic Sea, a similar scenario can be assumed there, as the stock structure is similar to that of the Gulf of Bothnia.

The new knowledge seems to have penetrated everywhere, except where it matters – with the decision-making politicians. In a press release, the outgoing government claimed that the quota decision means that “vigorous measures are taken and the precautionary approach is applied to recover the stocks that currently do not have a good stock status” – a conclusion that is at odds with the state of knowledge presented by the researchers. Nevertheless, the outgoing government went to the negotiating table with an improved position after Sweden’s position was raised in the Parliament’s EU Committee and the Environment and Agriculture Committee. The input from knowledgeable MPs led to Sweden asking the European Commission to improve the knowledge situation regarding the age and size structure of herring. This is crucial knowledge for future quota decisions and something that BalticWaters believes should be included in ICES’s advice for all species next year.

It is very positive that the members of the swedish parliament are pushing the issue and it is important for herring that the issue is pushed before next year’s negotiations and decisions.

New governance for fish

The situation for the Baltic Sea is acute. Sweden, together with the other Baltic Sea countries, has for a long time prioritised large-scale fishing over ecosystems and coastal fishing, thereby degrading the coastal environment and reducing the opportunities to fish for food. Instead of maximising the extraction of fish (regardless of the purpose of the catches), the countries need to think more long-term and protect the stocks to ensure the conditions for future fishing for food.

A new government is now in place, and in the government declaration it is pleasing to note that industrial fishing will be moved away from the Swedish coast. We don’t know exactly what this means yet, but a prerequisite for this to happen is that the ongoing scientific project to move the trawl limit is changed to move the trawl limit along the entire coast.

We don’t know if the new government will do what is required, but with the general increase in knowledge among both the public and decision-makers, it will at least be more difficult to continue overfishing in the Baltic Sea – under the radar.

Find out more about what the government needs to do in our memo “Necessary measures for the Baltic Sea fisheries policy 2022-2026“.

See also our press release “Quotas a major blow to the Baltic Sea“.

| 2023 quota | The Commission’s proposal | 2022 quota | |

| Herring | |||

| Central Baltic | 70 822 tons | 61 051 tons | 53 635 tons |

| Gulf of Bothnia | 80 074 tons | 80 074 tons | 111 345 tons |

| Western Baltic | 788 tons* | 788 tons* | 788 tons* |

| Gulf of Riga | 45 643 tons | 45 643 tons | 47 697 tons |

| Herring total | 197 327 tons | 187 556 tons | 213 465 tons |

| Sprat | 224 114 tons | 201 554 tons | 251 943 tons |

| Herring and sprat total | 421 441 tons | 389 110 tons | 465 408 tons |

| Western cod stock | 489 tons* | 489 tons* | 489 tons* |

| Eastern cod stock | 595 tons* | 595 tons* | 595 tons* |

| Plaice | 11 313 tons | 11 313 tons | 9 050 tons |

| Salmon | 63 811 pcs | 63 811 pcs | 63 811 pcs |

| Salmon Gulf of Finland | 9 455 pcs | 9 455 pcs | 9 455 pcs |

Table: The quota process starts with the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) proposing quotas. These proposals are based on policy frameworks that scientists need to adhere to. The Commission then makes a proposal that ministers use as a basis for their negotiations. Read more about the Commission’s proposal here.

* No directed fishing allowed. May only be caught as by-catch in other fisheries.

The new minister

Peter Kullgren (KD), minister for Rural Affairs and head of department at the ministry of Rural Affairs and Infrastructure, is the new minister responsible for fisheries. He was born in 1981 and has until now been the secretary of the Christian Democrats’ party.

He was previously a municipal councilor and chairman of Karlstad’s urban planning committee. As far as we have been able to find, he has never commented on fishing issues.

Photo: Ninni Andersson/Government Offices

Read our previous briefings here.