Council of Ministers ignores Commission proposal

The decision taken by the Council of Ministers earlier this week on the 2024 fishing quotas in the Baltic Sea is in many ways unique. It shows a remarkable historical short-sightedness, ignorance of the fish and fishing in the inland sea, inability to understand the scientific advice of the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) and – perhaps most of all: the ministers are bending the laws that regulate fishing, ecosystems and the marine environment to the limit.

As a result, the majority of all herring fishing will continue to be carried out by large-scale industrial fishing – a fishery where the catch becomes fishmeal for salmon farms, mink farms and chicken production, and where the catches are mainly landed in Denmark. The decision also makes it more difficult for herring, as it is known north of the Kalmar Strait, to grow back and will most likely lead to a continued decline in stocks in the Baltic Sea.

The Minister for Rural Affairs, Peter Kullgren, is thus contributing to the continued depletion of the Baltic Sea ecosystem – a development that in no way favours the small-scale fishing that he says he wants to protect.

Below we discuss the background to, and effects of, next year’s herring quotas and suggest three decisions that the Swedish Minister for Rural Affairs must take this year to minimise the damage to the marine ecosystem.

Cod déja vu?

Despite all the signs that Baltic cod was in crisis, the Council of Ministers continued to allocate quotas, which the then Swedish Minister for Rural Affairs was happy with. Cod fishing had to be allowed in order to prevent the disappearance of an entire industry, they argued. Just like today, the small-scale fisheries were used as an argument to continue fishing, while the majority of fishing was carried out by large-scale trawlers.

The result was a collapsed cod stock that has still not recovered. And now, just 4 years later, we are about to repeat the same mistake.

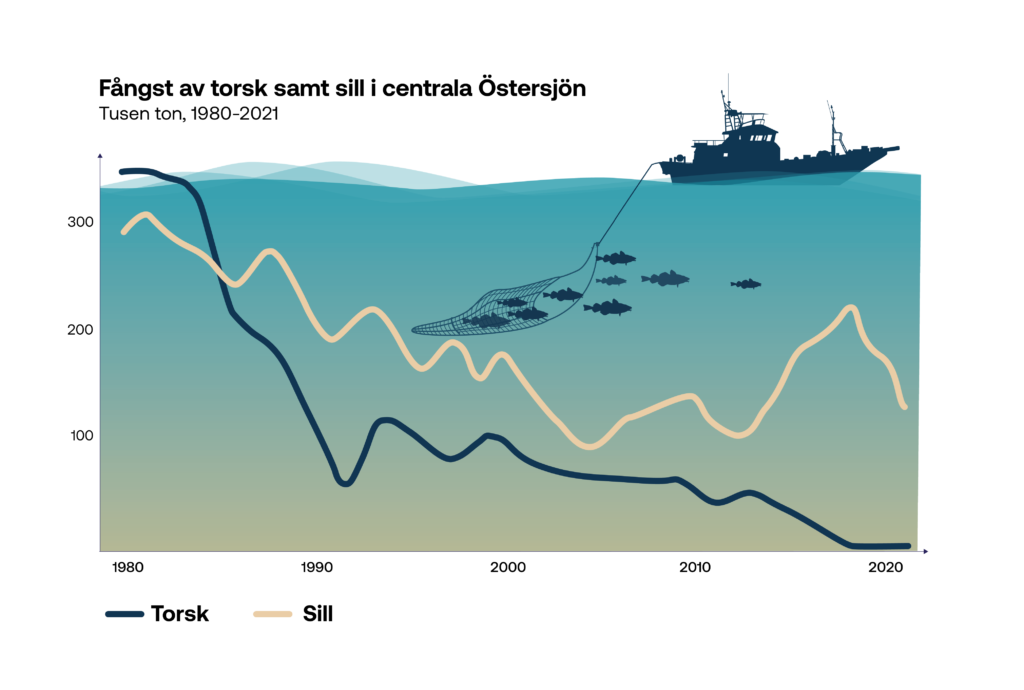

Graph: Fångst av torsk samt sill i centrala Östersjön, Tusen ton, 2980-2021 = Catch of cod and herring in the central Baltic Sea, Thousand tonnes, 1980-2021; Torsk = Cod; Sill = Herring.

Herring stocks and catches in the central Baltic Sea have declined by 80% since the 1990s. Scientists and coastal fishermen report that it is increasingly difficult to catch large herring for human consumption. Since 2019, there has been a ban on cod fishing in the once vast eastern stock of the Baltic Sea.

Does Minister Kullgren understand the fishery?

The Minister for Rural Affairs, Mr Kullgren, finds it difficult to distinguish between different parts of Swedish fishing. Industrial fishing and small-scale fishing have very little in common, even though the representatives of industrial fishing have skilfully made it appear so. On the contrary, it is probably the effects of industrial fishing that have caused the disappearance of the larger herring from the coast and that have essentially contributed to depletion. The contribution of industrial fishing to Swedish fisheries is the transhipment of catches to lorries that are driven to Denmark to become feed. Small-scale fishing provides us with sour herring, fish in local shops and restaurants.

At the same time, several small-scale fishermen have spoken out in the media in favour of lower quotas, or even a ban on herring fishing, to help stocks recover. Industrial fishing in the Baltic Sea lasts a few months a year and then continues elsewhere in the world. Small-scale fishing takes place in the same waters, all year round. Mr Kullgren needs to stop talking about a fishing industry and focus on what the government can do to save and protect fish and small-scale fishing.

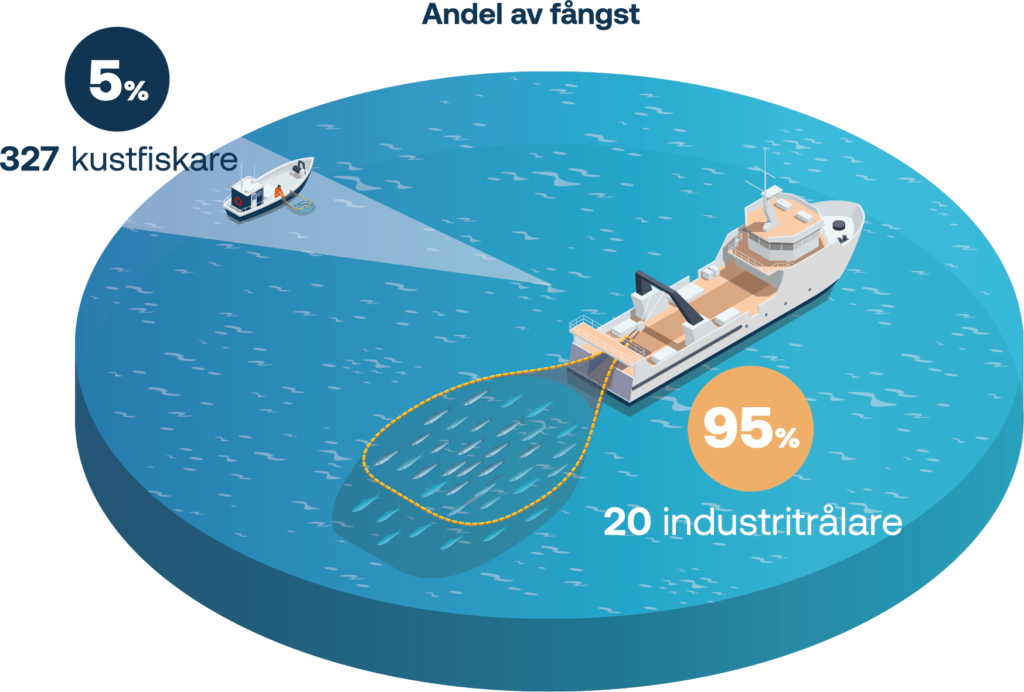

Illustration: Andel av fångst = Share of catch; Kustfiskare = Coastal fishermen; Industritrålare = Industrial trawlers.

Between 2021 and 2022, over 100 Swedish small-scale boats stopped fishing in the Baltic Sea, a loss of a quarter in just one year. Yet almost as many fish were caught. This is due to continued high quotas and the increasing efficiency and size of the largest vessels. In total, the 20 largest vessels catch 95 per cent of the fish in the Baltic Sea. The majority of the fish caught is used as feed.

Sprat and by-catches

The Council of Ministers granted a sprat quota of 201,000 tonnes for next year. A modest 10% reduction, despite the fact that the sprat stock is also showing early signs of trouble. Recruitment, i.e. the new age classes, is the worst ever. With the exception of a very small proportion landed for human consumption in the Baltic countries and Poland, sprat is fished by industrial trawlers for fishmeal production.

Industrial trawling for sprat also has an impact on herring, as sprat fishing leads to significant by-catches of herring. The Commission proposal included a by-catch quota of approximately 28,000 tonnes of herring for the central Baltic Sea. The Council of Ministers’ quota decision does not mention a specific by-catch quota. Given the non-existent control of industrial sprat fishing, there is a high risk that herring will be caught and reported as sprat. If by-catches are as high as 28,000 tonnes, or even more if you look at previous by-catch figures, the total catch will hit the Baltic herring very hard.

Could the Council of Ministers have broken the law?

The Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) is a specific policy area within the European Union framework, operating within the legal framework established by the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). The TFEU is the overarching treaty that establishes the EU’s competence and legal basis for various policies, including the CFP.

In other words, the CFP derives from, and operates within, the framework established by the TFEU. In essence, the TFEU is the basic legal document governing EU decision-making, but it is through subsequent legislation and policies that detailed measures and rules are established in different areas.

The Council of Ministers‘ decisions may therefore violate a number of laws and directives that specifically regulate fisheries, ecosystems and the marine environment, contrary to what fisheries ministers claim in the press release from the meeting. However, from an overall perspective, and by relying on the EDF, the decision can be considered legal.

How does this decision relate to the more specific laws?

- The decision may violate the EU’s Common Fisheries Policy (CFP), which states that ‘fishing activities shall be conducted with due regard for the ecosystem and shall ensure that adverse impacts of fishing activities on ecosystems are minimised’.

- The decision is also likely to be in breach of the multi-annual management plan for the Baltic Sea, which is an important tool for achieving the requirements of the CFP, §4:6 of which states that ‘Fishing opportunities shall be set in such a way that there is less than 5% probability that the spawning stock biomass will fall below the Blim’ See box for further information on the Blim.

- Finally, the decision may violate the Marine Strategy Framework Directive which states that the sea and its biological life should be in ‘Good Environmental Status’, and that the populations of all commercially exploited fish should be kept within safe biological limits.

What is right or wrong is for the courts to decide. What we do know is that the Baltic herring is the food base of the ecosystem and is therefore a species that feeds everything from marine mammals to birds and other fish. If the herring disappears, we could be facing one of the greatest environmental disasters in the history of the Baltic Sea.

Fact box

The International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) states in its assessment that even at 0 quota, the assessment is that the herring in the central Baltic Sea has a 22 per cent risk of falling below Blim, which is a critical point for the stock as the survival of the stock is threatened. In the EU, the biomass of a spawning stock, Blim, is defined as the stock size below which recruitment – i.e. the addition of young fish to a population, has a high probability of being ‘impaired’. If the stock biomass falls below Blim, ICES recommends measures to rebuild the biomass, such as further reduction or cessation of directed fishing.

How do we move forward?

Despite the difficult situation, there are still some decisions that Minister Kullgren can implement to minimise the damage, but he will have to push ahead with previously decided processes and be quick to write new directives to the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management and the Coast Guard:

Effective control of industrial fishing must be introduced immediately. The Coast Guard must be given a mandate and tools to carry out controls of fishing at sea so that illegal catches are reported and cheating fishermen fined – order and accountability must be established in fishing.

Extend the trawl limit along the entire east coast. As early as 2021, a majority of the parliamentary parties decided that they wanted to see the trawl limit moved along the entire east coast. The Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management is working on a trial in some areas. It is insufficient and it is moving too slowly. The Minister has the opportunity to act and ensure that the entire east coast is protected from industrial trawling.

Instruct the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management to formulate measures that lead to the majority of the Swedish herring quota being landed by small-scale fishermen who fish for human consumption, and where the quota is landed in Sweden.