One day in October 2023, EU fisheries ministers decided to continue the targeted herring fishing in 2024, despite the recommendations of the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) and the European Commission’s (the Commission) original proposal for a stop. The quota decision has been widely criticised, both for its appropriateness and legality. Was the EU Council of Ministers (the Council) legally entitled to take such a decision, which seems to go against several of the laws and rules that, according to EU law, should guide the management of fisheries in the Baltic Sea?

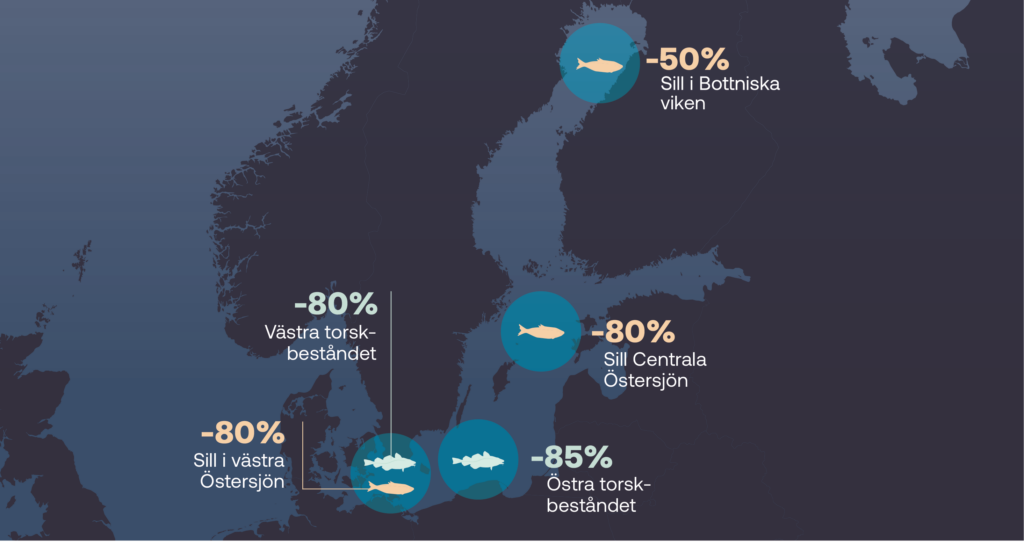

The development of herring compared to peak levels. In the Central Baltic Sea, herring stocks have declined by over 80 per cent compared to the 1970s. In the last four years, the stock has declined by 40% and is now at a critical level. In the Gulf of Bothnia, the herring stock has declined by over 50% since the early 1990s. In the western Baltic Sea, herring stocks have declined by over 80 per cent since the early 1990s. Source: ICES Advice 2022, Illustration: Sofie Handberg. Sill i Bottniska viken = Herring in the Gulf of Bothnia, Sill i Centrala Östersjön = Herring in the Central Baltic, Sill i västra Östersjön = Herring in the Western Baltic.

EU fisheries ministers sit behind closed doors as they decide on tomorrow’s fisheries – a decision that affects not only the future of the sea and fisheries, but also your, my and future generations. At first, things seemed to be going in the right direction for herring – both ICES and the Commission took the weak development into account and followed the law. But when the issue came to the table of the fisheries ministers, something happened – they did not listen to the Commission’s proposal to stop targeted herring fishing and ignored the core of ICES’s scientific data. When the criticism came, they tried to circumvent democratic processes to legitimise their actions.

The quota process

Prior to the annual meeting of EU fisheries ministers and the final decision, several processes take place. The quota process, as it is often called, starts with ICES providing scientific advice on fish stocks. The scientific information then forms the basis for the proposal prepared by the Commission. This proposal is submitted to the EU fisheries ministers (The Council). The ministers finally meet in Brussels in October each year and decide on fishing quotas, based on the commission’s proposal.

You can read more about what went wrong during the 2023 quota process here (in Swedish).

The Council’s decision cannot go unnoticed. There are simply too many legal questions and obvious missteps. To analyse what happened and to better understand the ministers’ actions, we asked David Langlet, Professor of Environmental Law at Uppsala University, to review the legal sources surrounding the EU fisheries policy and assess whether the Council acted within the limits of its mandate. This Baltic Sea Brief summarises Langlet’s report and his and our conclusions. Read the full report “Are EU fisheries ministers breaking the law? a legal review of political decisions concerning fisheries in the Baltic Sea” here.

Background to the decision on the 2024 herring fishery in the central and northern Baltic Sea

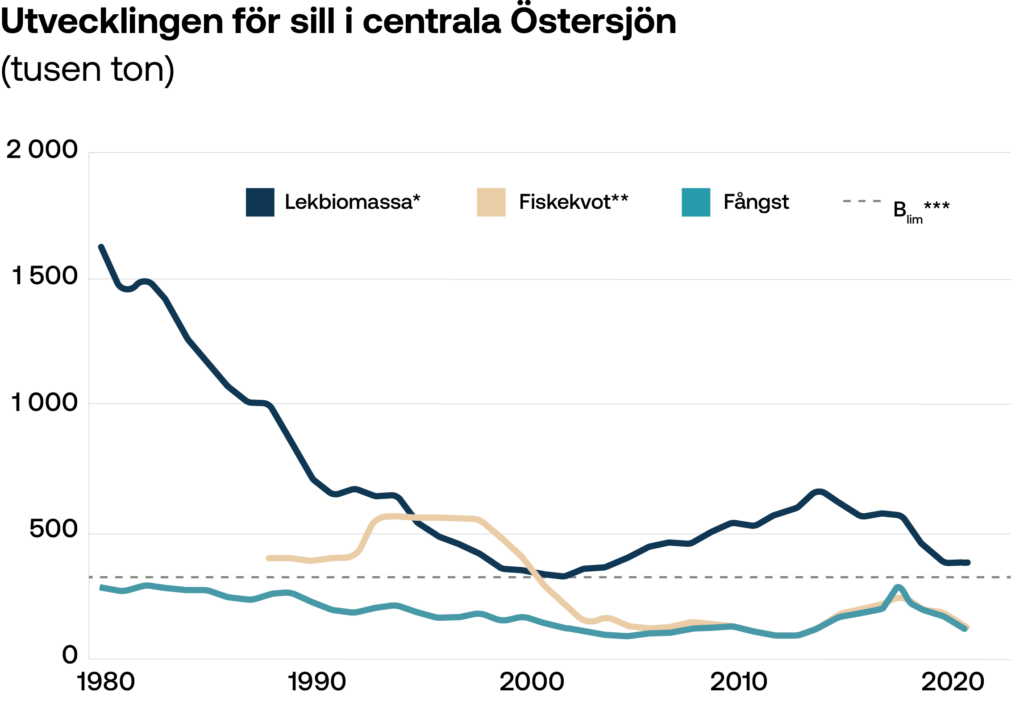

For the central herring stock, ICES estimates that spawning biomass has been just below or just above the critical limit known as Blim for most of the last 30 years, including the most recent years. If a fish population is at or below Blim, there is a high probability that the stock can no longer recover. Even if all fishing for herring were to cease in 2024, there is a 22% probability that stocks will remain below Blim in 2025, i.e. that they will not recover – despite the cessation of fishing. We are now seeing the results of decades of intensive fishing at the limit of what the herring stock can sustain. In light of the ICES advice, the Commission proposed that no directed fishing be allowed and only low levels of “unavoidable by-catch”. Although both ICES and the commission advised against directed fishing, the Council decided on a targeted catch quota (TAC) of 40 368 tonnes for 2024.

Utvecklingen för sill i centrala Östersjön (tusen ton) = Development of herring in the central Baltic Sea (thousand tons), Lekbiomassa* = Spawning biomass, Fiskekvot* = Fishing quota**, Fångst = Catch.

The part of the stock that has reached sexual maturity. ** ICES reports historical quotas (TACs) from the late 1980s. *** Reference value when the spawning biomass is so low that reproduction is threatened, which should lead to further reductions in quotas or closures (ICES). Source: ICES Advice on fishing opportunities, catch, and effort, ICES2022.

For the herring stock in the Gulf of Bothnia, the spawning stock biomass is below Btrigger (a kind of warning signal, see glossary) and ICES assesses that there is a 9% probability that the stock will decline to below Blim in 2025 – even with no fishing. The Commission proposed that no directed fishing be allowed and only low levels of “unavoidable by-catch” to avoid stopping fishing on other species in the mixed fishery in the Bothnian Sea. The Council decided on a TAC of 55 000 tonnes.

“Unavoidable by-catch”

In the Baltic Sea, fisheries are managed species by species, although in practice there is what is known as a mixed fisheries – i.e. where other species are caught in a targeted fishery. For example, when fishing for flatfish, the by-catch is cod and when fishing for sprat, herring is also caught. Under current management and legislation, herring in the Baltic Sea is not regarded as a by-catch.

If different catches of herring are summed up for the central Baltic Sea – i.e. a decided targeted quota of 40,000 tonnes, an estimated by-catch of herring, mainly in the sprat fishery, of more than 40,000 tonnes and the Russian quota – which has historically fluctuated around 25,000 tonnes, the herring harvest in 2024 is summed up to at least 105,000 tonnes. This is despite the fact that both ICES and the Commission have advised against targeted fishing for herring in the central Baltic Sea because the stocks are below the level where they can reproduce.

Laws and frameworks regulating EU fisheries

There are two basic treaties that govern the EU’s activities and institutional framework and are considered hierarchical within the EU’s legal structure. The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) is one of the treaties. It contains provisions on the EU institutions, their powers, and functions, as well as rules for EU policies – such as fisheries. Article 43 TFEU contains two different legal bases related to fisheries. Article 43(2) TFEU enables the European Parliament and the Council to adopt laws and plans relating to fisheries. Article 43(3) TFEU gives the Council the sole right to decide on the fixing and allocation of fishing opportunities, but these decisions must comply with the legal framework established under Article 43(2).

The first more comprehensive EU legislation setting out principles for fisheries came in 1983 in the form of the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP). The main purpose of the CFP was to allocate resources between Member States. Over the years, laws have been reformed and plans put in place to ensure that fisheries and aquaculture activities are environmentally, economically and socially sustainable. However, the principle of ‘sharing the resource at all costs’ remains and permeates quota decisions year after year, despite clear regulations and requirements that fishing should only be carried out if it does not jeopardise the long-term survival of fish populations.

In addition to the TFEU and the CFP, there are two other legal sources that the Council has to consider, the Multiannual Management Plan for the Baltic Sea (MAP) and the EU Marine Strategy Directive (MSFD). MAP and the MSFD have been in place since 1983 to ensure the long-term sustainability of fisheries. For a more thorough introduction to all sources of law, read the full report here.

Legal violations by fisheries ministers

The Council based its decision on fishing quotas for 2024 on the TFEU, more specifically Article 43(3). Although the Council has a margin of discretion under this article, their decision must be in line with the legal framework established under Article 43(2), i.e. the CFP and MAP – but also the MSFD. Already here the Council has committed a violation – they cannot legally take decisions under 43(3) TFEU without considering 43(2). But it does not end there.

Violation in relation to the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) and the Baltic Sea Multiannual Management Plan (MAP)

The objective of restoring and maintaining stocks above levels that ensure Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY, a management principle for calculating the maximum sustainable yield that can be taken from a species’ stock), was, according to the CFP, to be achieved progressively over the period 2015 to 2020. After 2020, there is a requirement for exploitation to be consistent with MSY. It is now 2024 and neither the herring in the Central Baltic Sea nor in the Gulf of Bothnia have reached the prescribed levels at which sustainable fishing can be conducted. The law states that “all appropriate remedial measures” should be taken to ensure that stocks return rapidly to levels that ensure MSY. These clear objectives have not been met.

The EU’s attempt to change legislation

Shortly after the decision on the 2024 catch levels for the Baltic Sea, and the criticism it received, the Commission made a proposal to remove the 5% rule from the regulation establishing the multiannual plan for the Baltic Sea. The proposal, and its timing, can be interpreted as an indication that the Council and the commission recognise that the 5% rule in the MAP is in fact an obstacle to the decisions the Council took in October 2023.

It is also evident that the Council’s decision, for herring in both the Central Baltic Sea and the Gulf of Bothnia, is not compatible with the requirement in the MAP that fishing opportunities should be set in a way that ensures that the probability is less than 5% that the spawning stock biomass is below the critical limit B lim (the five per cent rule). For the stock in the central Baltic Sea, ICES has assessed that there is a 22% probability that it will remain below Blim 2025 even if no catches are made in 2024, and for the Gulf of Bothnia the corresponding probability has been assessed at 9%. MAP thus says that under current conditions no directed fishing can be carried out.

It is difficult to see how the Court of Justice of the European Union, if the matter came under the Court’s scrutiny, could reach any other conclusion than that the Council has acted outside the limits of its mandate by not respecting the so-called five per cent rule in the MAP when deciding on quotas for herring stocks in the Baltic Sea. In addition, the Council has not followed the principle that fishing should be conducted at MSY as current utilisation does not enable sustainable reproduction of fish.

Violation in relation to the EU Marine Strategy Framework Directive

The Council’s decision on catch levels can also be questioned in terms of compatibility with other EU legislation. The CFP must be compatible with the Union’s environmental legislation, in particular with the objective of achieving good environmental status under the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD), which should have been achieved by 2020. For this to be considered achieved, the populations of all commercially exploited fish species must, among other things, remain within safe biological limits and show an age and size distribution that indicates a healthy stock. According to scientific advice, the high exploitation of herring is not within safe limits, at least not to the extent that the spawning biomass is or risks falling below the critical limit Blim. It is also well documented that fishing has a major impact on the size and age structure of stocks.

A decision that goes against several laws and should be reversed

BalticWater’s assessment is that the Council has acted outside the limits of its mandate when deciding on the 2024 fishing quotas.

- The Council violates the TFEU by basing the quota decision on Article 43(3). The Council’s decision must be aimed at implementing the CFP and remain within the framework set by the legislation. Even if the Council has a margin of discretion, it cannot legally take decisions that go against the requirements formulated in the CFP and MAP, among others.

- The Council violates the CFP by ignoring MSY targets and the requirement to take action if fish stocks show signs of decline.

- The Council violates the MAP by ignoring the 5% rule when setting fishing opportunities (in addition, the process of the legislative amendment to remove the 5% rule is legally and democratically questionable).

- The Council violates the Marine Strategy Framework Directive and the objective of achieving good environmental status, which should have been achieved by 2020.

The legal review shows that the Council has acted in contravention of existing laws, and that if the issue had been subject to judicial review, it is difficult to see how the European Court of Justice could come to any other conclusion than that the Council has acted outside the limits of its mandate. The Council has also failed to deal with the issue of the 5% rule when trying to push through a change in the law outside of established democratic processes.

This shows that politicians are not taking the situation seriously, the sea will not be saved by decision-makers removing or rewriting laws that exist to protect our shared natural resources, natural values, and the marine environment. If the trend is to be reversed, lawlessness and empty words must be replaced by courage and environmental concern. Scientific advice must be followed, quotas must be zero if the survival of fish populations is at stake, and there must be monitoring to ensure that everything is done correctly – apparently not only at sea, but also in the meeting rooms of the Council.

Glossary

Blim If a stocks biomass is at or below the Blim limit, there is a high risk that the stock no longer recovers.

Btrigger If a stock’s biomass reaches the Btrigger limit, ICES must recommend management measures to restore it to a level that achieves MSY in the long term.

TFEU The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

CFP The EU’s common fisheries policy.

Spawning biomass Spawning biomass is the part of a fish stock that has reached sexual maturity and can contribute to the survival of the stock.

MAP Multiannual Action Plan – den fleråriga förvaltningsplanen för Östersjön.

MSY Maximum Sustainable Yield – the largest average catch or yield that can continuously be taken from a stock under existing environmental conditions.