– Circular fertiliser also a preparedness issue for Sweden

22 million tonnes of animal manure are produced every year in Sweden. All of it is used on our fields, but not in a sufficiently resource-efficient way and access to animal manure is unevenly distributed in our country. As part of the Circular NP project, researchers are trying to optimise animal manure so that it is both efficient and easy to transport. But economic incentives are needed to promote the circular use of fertiliser on a larger scale, the industry says.

– “If we want more healthy nature and less algal blooms in the sea, then we must also pay a little more for food,” says Markus Hoffman of The Federation of Swedish Farmers, who also points out that it is a matter of preparedness for Sweden to have access to its own fertiliser.

In 1909, artificial ammonia was produced for the first time. This was the start of a revolution in agriculture: ammonia, a compound of nitrogen and hydrogen, could be used to produce mineral fertiliser. Until then, we had had to rely on animal manure. But with the availability of artificial fertilisers, known as mineral or chemical fertilisers, our food production changed fundamentally.

– “Mineral fertiliser was less labour-intensive and easier to handle than animal manure. There was a fairly rapid change in agriculture between the 1950s and 1980s,” says Markus Hoffman of The Federation of Swedish Farmers.

The change allowed for larger harvests and higher yields. Global food production quadrupled as a result of mineral fertilisers, and today provides nutrients for half of the world’s agricultural crops.

Markus Hoffman. Photo: The Federation of Swedish Farmers

With the introduction of mineral fertiliser into Swedish agriculture, it was suddenly possible to grow crops without keeping animals. This led to extensive regional specialisation, with farms mainly either producing crops or raising animals. This development has created an imbalance in the availability of nutrients in different parts of the country.

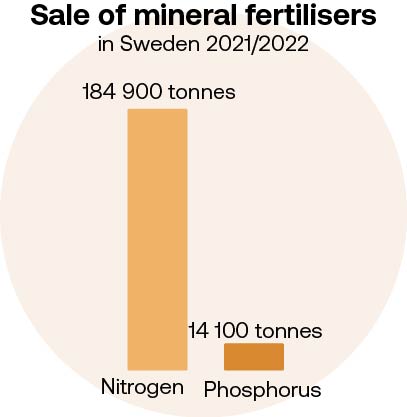

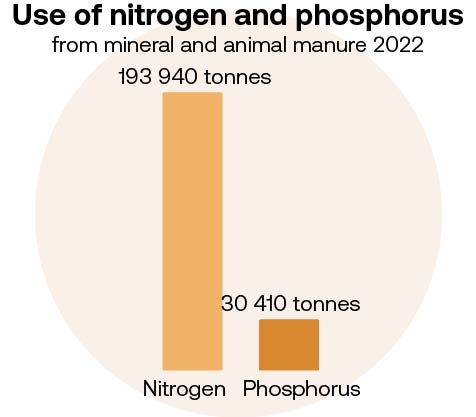

Source: Swedish Board of Argriculture

– “Farms with their own animals are largely self-sufficient in terms of nutrition, but many also supplement with mineral fertiliser,” explains Markus Hoffman.

There is a high risk of nutrient overload on large animal farms, despite legislation regulating the use and application of fertilisers. This can cause nutrients to run off and eutrophy waters. Globally, the efficiency of fertiliser use is reported to be as low as 42 per cent.

Helena Aronsson. Photo: Heidi Hendersson

– “The nutrients are not being used efficiently,” says Helena Aronsson of SLU, who in the collaborative project Circular NP – Better nutrient cycle for animal manure with BalticWaters and Research Institutes of Sweden (RISE) is looking at how to develop a better cycle for animal manure that also includes transport between fertiliser-rich and fertiliser-poor areas.

There is a need to use fertiliser more efficiently – because there is no shortage of nutrients. Animal husbandry in Sweden produces about 22 million tonnes of manure annually and could replace some of the mineral fertiliser used in crop production. But animal manure is mostly water, which makes the volumes large and expensive to transport.

– “We have these huge amounts of animal excrement and one of the big problems with both use and transport is that it is very watery,” explains Helena’s colleague and researcher Athanasios Pantelopoulos, who is experimenting with ways to optimise the fertiliser value.

From 200 grams to 80 grams

The first step in the project process was to separate the liquid from the animal manure into a lighter, dry fraction that is rich in phosphorus and contains a lot of organic material. But even the dry fraction still contains a lot of water, as much as 60-70 per cent.

– “It is both heavy to transport and bulky to store in anticipation of spring fertilisation. The dry content therefore needs to be further increased to create a product that is cost-effective to transport. A high moisture content can also cause the product to compost, which can lead to a loss of nutrients,” says Athanasios.

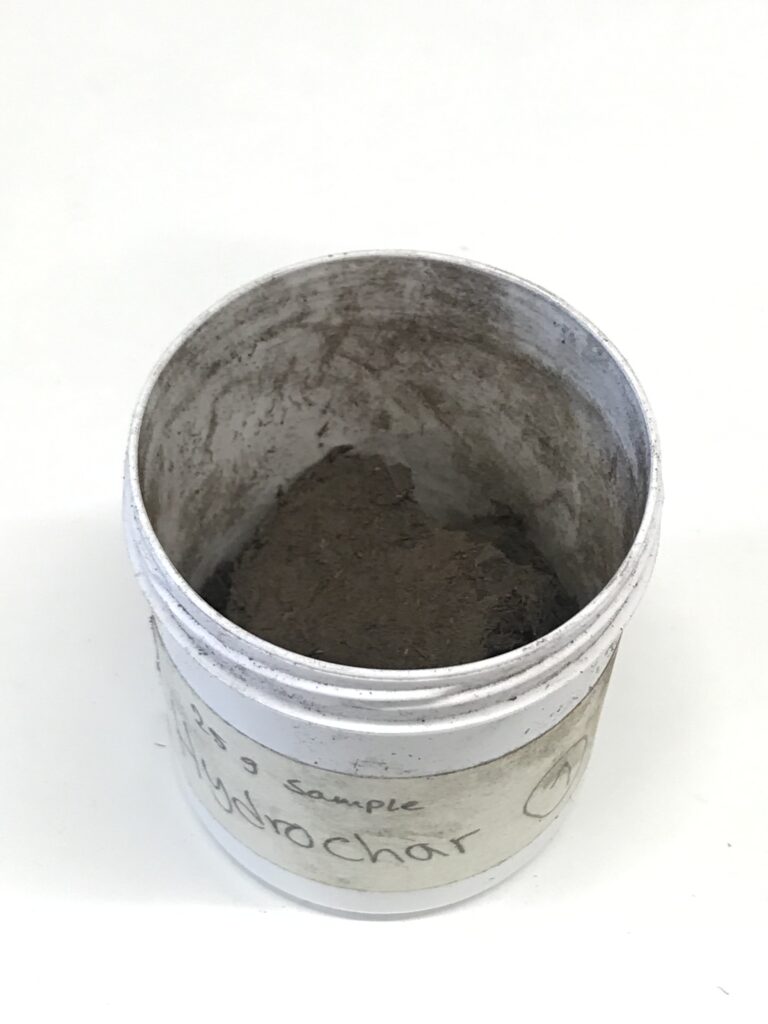

He shows us into one of the labs in the SLU building. There are transparent plastic boxes containing the experiments being carried out as part of the project. He lifts the lid of two boxes, one that appears to be filled with a black carbon-like material and one with small soil pellets. The latter is called biochar and is produced by heating in an oxygen-free environment up to 800 degrees.

– “We fill a metal container with 200 grams of fertiliser and take out 80 grams of biochar after heating it for a few hours,” explains Athanasios.

– “We will now conduct a six-month experiment with the carbon in soil conditions similar to those in the field,” says Athanasios.

Before closing the boxes, he pauses.

– “Do you smell anything?” he asks.

I sniff the air. Nothing.

– “You should smell the animal manure before it is treated,” says Helena.

Athanasios Pantelopoulos. Photo: Heidi Hendersson

The strong odour from untreated animal manure Helena refers to is ammonia, which forms particles that are harmful to health and contributes to acidification and eutrophication of the Baltic Sea and other water bodies. 90 per cent of ammonia emissions to the air in Sweden in 2022 came from agriculture, of which 78 per cent came from the storage and spreading of animal manure.

– “By having a closed process for treating the fertiliser, we also want to reduce emissions of both ammonia and greenhouse gases, such as methane,” Helena explains.

Biochar from digestate solids separated by centrifuge. Photo: Heidi Hendersson

Hydrochar from digestate. Photo: Heidi Hendersson

A link on the path to circular fertiliser use

Launched in 2021 and running until 2026, the Circular NP project aims to find solutions, disseminate knowledge and provide examples of how animal manure can be used in a smarter way.

“Our task is not to develop a finished product for the market. We are a link on the road to show possible methods to achieve sustainable and efficient fertilisers that are attractive to farmers,” says Helena.

Does it seem that the industry is interested?

“Yes, but when will it happen? Everyone can see the need and the benefits, but someone has to take the risk for something to happen,” she says.

– “The mineral fertiliser we use today is not circular. Farmers would rather buy and fertilise with circular fertiliser, which would also improve the sustainability profile. But it is ultimately about price. If the circular fertiliser is more expensive, farmers need to be compensated,” he says.

– “As the situation is now, farmers cannot pay more for a circular product. But maybe food producers could reward goods made with circular fertiliser? Helena asks.

We take this question to Åsa Domeij, Head of Sustainability at Axfood – would this be a winning concept?

Åsa Domeij. Photo: Elin Andersson

– “It sounds very interesting,” she says.

Where the extra cost for the customer comes in depends on whether you choose to incorporate the premium into the sale of the raw material, such as flour, or a more processed product, such as bread.

– “If you sell a loaf of bread, the extra cost is hardly noticeable, because the customer pays primarily for the bread,” says Åsa.

One challenge, however, is to get consumers to understand the added value of paying for goods where circular fertiliser has been included in the process. Consumers are now familiar with organic and Fairtrade, but different types of sustainable fertiliser are new to most people. However, it has already entered the market.

– “The food company Lantmännen has a farming concept called “Climate & Nature” where farmers who grow wheat with fossil-free mineral fertiliser are paid more. But you have to pay a little extra for that package of flour when you shop, and not everyone wants to do that. A flour package from Nature and Climate costs SEK 3 more,” says Markus Hoffman.

Circular fertiliser use is also a preparedness issue

It remains to be seen what the extra cost of increased and more efficient use of circular fertiliser would be in practice, but farmers are certainly on board. SLU has conducted a study in which they asked farmers how much animal manure they use today and how much they would like to use in the future, and more than half indicated that they want to increase their use.

– “It’s not just about wanting the nutrients, animal manure also helps to improve soil health,” explains Helena Aronsson.

Many farmers are also open to fertiliser from sludge and human urine. Studies show that if all these forms of fertiliser were combined, Sweden could meet 75 and 81 percent of the total nitrogen and phosphorus needs of agriculture.

Both Helena Aronsson and Markus Hoffman also emphasise that a circular cycle is important for Swedish preparedness. As things stand today, Sweden imports all its mineral fertiliser from abroad, which makes Sweden more vulnerable in the event of a crisis. But research projects like Circular NP show that there are great opportunities to increase self-sufficiency by making the circular fertiliser we have at home more efficient. What is missing are the economic incentives for further development and large-scale production of, for example, the biochar produced in the project.

– “There is a huge lack of money and this has been the case for quite a few years,” says Markus Hoffman, who has helped produce a report on the costs of the green transition of Swedish agriculture.

The report estimates that the transition will cost SEK 80-85 billion in investments on farms and a further SEK 10-11 billion in annual costs. Some of this could be covered by political support and subsidies, but in the long term, food prices need to be raised and the rate of investment increased. Within the Circular NP project, there have been some contacts with companies interested in biochar in particular, but so far these are small-scale players.

– “It’s difficult for these small companies to compete with large producers of commercial fertilisers. But we hope that we can show solutions and examples of optimising animal manure, and then we’ll just have to wait and see,” says Helena.

About Circular NP

The project Circular NP – Better nutrient cycle for animal manure is carried out by BalticWaters in close co-operation with the Swedish Univeristy of Agricultural Sciences and Research Institutes of Sweden (RISE).

The project aims to develop technologies to bind nitrogen and extract phosphorus from animal manure and produce new fertiliser products that can be more easily transported over longer distances, from areas with a phosphorus surplus to areas with a deficit.

More information on Circular NP can be found on the project page.