Sweden and Finland are two of the Baltic Sea nations that fish the most herring. They are also the two countries that fish the absolute majority of the fish in the Gulf of Bothnia. However, attitudes differ in politics, research, and public opinion in regards to the popular fish. In a series of articles, BalticWaters examines the reasons for the difference in views on herring in Finland and Sweden.

The research: Sweden focuses on fishing pressure, Finland on environmental factors

The researchers in Finland do not believe that a fishing ban on herring is necessary. Instead, they want to focus on combating eutrophication and improving coastal environments. Swedish researchers, on the other hand, are concerned about the high fishing pressure and advocate for a zero quota.

“I find it difficult to grasp how the discussion can be so completely different,” says SLU researcher Ulf Bergström, who has a foot in both countries.

Two years ago, the Finnish Natural Resources Institute published a report on malnourished larger herring in the Gulf of Bothnia, news that reached beyond the news threshold in a country where there has otherwise not been as much debate or concern about herring as in Sweden.

However, in recent times, the reseachopinion in Finland has been more positive regarding the health of herring – and this also influenced the discussion about fishing quotas for 2024. In the first part of BalticWaters’ in-depth exploration of the herring issue across borders, it became clear that criticism of continued large-scale industrial fishing has largely been absent in Finland.

The reason for the positive outlook, according to the Natural Resources Institute, is improved food conditions, especially the presence of mysis relicta (a shrimplike crustacean).

“Mysis relicta seem to have recovered, and it affects the herring. This year, I opened the stomachs of some herring, and there were mysis relicta,” says researcher Jari Raitaniemi, referring to this year’s joint research trip with Swedish researchers that has recently concluded.

According to him, the risk of a stock collapse is now much smaller, at least in the northern parts of the Baltic Sea. This was also information provided to the Finnish Parliament ahead of negotiations with the EU on fishing quotas.

“We already saw in the spring that the situation was improving and that the fish were fatter, but it’s not statistics that have been included in this year’s advice by ICES.

Joint Research Expedition

The annual research expeditions are conducted in collaboration between the Natural Resources Institute and the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SLU. The research is part of the Baltic International Acoustic Survey (BIAS), an commitment under the EU’s Common Fisheries Policy coordinated by the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES).

Based on research data from 2022, ICES announced in June that the spawning stock of herring in the Gulf of Bothnia was close to the critical threshold. The spawning stock for the herring population in the Baltic Sea Proper was estimated to be below the critical threshold. This knowledge influenced the European Commission when, in August, they proposed a 0 quota for all targeted herring fishing in the central and northern Baltic Sea.

“The proposed Total Allowable Catches (TAC) are based on the best available scientific advice from ICES and follow the multiannual management plan for the Baltic Sea adopted in 2016 by the European Parliament and the Council,” the Commission wrote in its decision

But Swedish researchers find it challenging to understand why their Finnish counterparts are so optimistic.

“What matters is still that the risk of the stock falling below Blim is considerably higher than what multi-year plans allow,” says Ulf Bergström, a Baltic Sea researcher at SLU, originally from Finland.

He does not find it reasonable to place such emphasis on food availability and the condition of the herring, as is done in Finland, since it is the stock size that should be the basis for quota decisions.

“Sure, food availability is important and is part of the problem, but those aspects are not considered in quota setting. It is solely the biomass on which the quota recommendations are based.”

The skinny herrings from 2021. Photo: Naturresursinstitutet.

It was last year that the real discussion regarding lost biomass and, in particular, a shortage of large herring in the Baltic Sea got started. In the Swedish debate, large-scale industrial fishing was pointed out as the culprit, while researchers in Finland believed that the problem was a lack of food.

“Some of the large herring have been so thin that they probably died of starvation in the sea,” wrote Jari Raitaniemi with his colleague Jukka Pönni in a op-ed in the Finland-Swedish newspaper Vasabladet in November last year.”

But the fishing pressure doesn’t completely escape the Natural Resources Institute’s descriptions of the situation. On their website, it is stated that the spawning biomass of herring in the Baltic Sea has decreased throughout the 2010s, and the cause is attributed to fishing quotas and the record-breaking catches, which exceeded 100,000 kilograms for six consecutive years. Jari Raitaniemi agrees that it was unsustainable and harmful.

“We should not, for the foreseeable future, or ever, return to such high levels of fish extraction.”

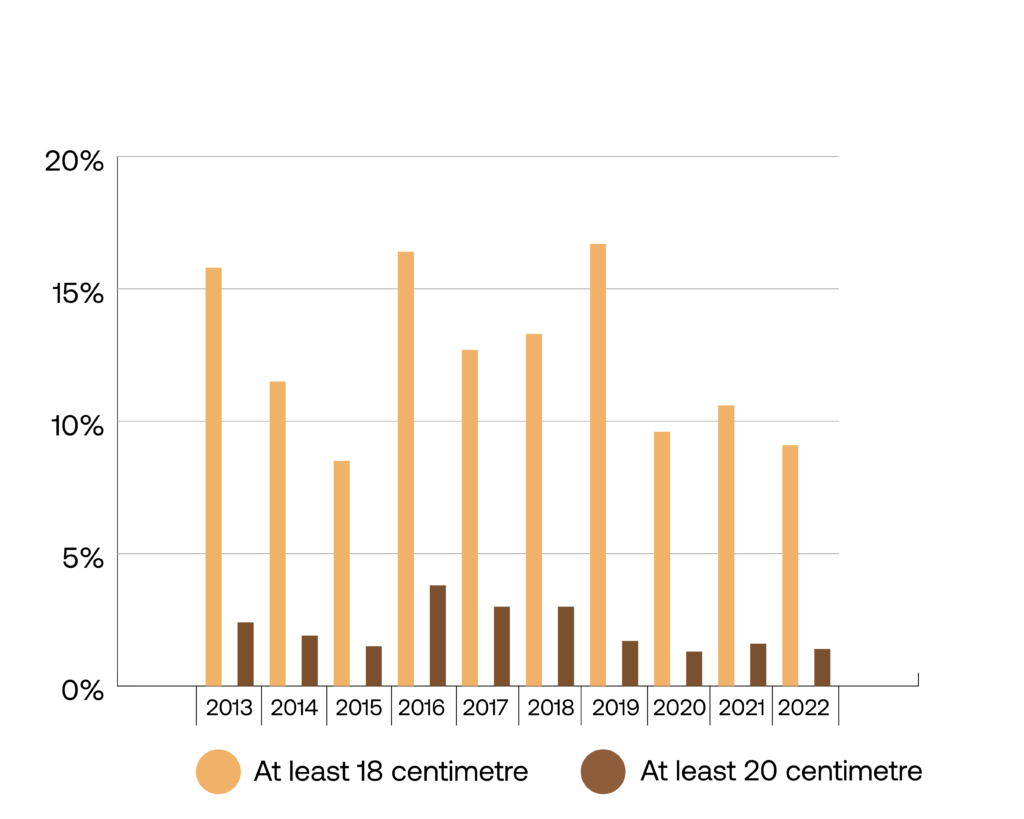

The proportion of catches for herring with a total length of at least 18 cm and at least 20 cm during trawl surveys from 2013 to 2022.

Source: Natural Resources Institute.

Swedish researchers advocate for wiser management

However, many Swedish researchers argue for a complete fishing ban on herring and sprat. One of them is Henrik Svedäng at Stockholm University. He states that the stocks have decreased over the past 10-15 years, primarily due to fishing.

“What the Finnish and Swedish data show is that the older fish are significantly fewer than before, and this is due to extensive fishing. A very large amount of fish has been taken, which ultimately affects the entire system. But, I can agree, there are also other factors that contribute to the decrease in productivity within the stocks.

He concludes that regardless of the perceived cause of the decline in the stock’s spawning biomass, the solution is to fish less. He also emphasizes the importance of herring for the Baltic Sea and the reason why many Swedish researchers view the situation critically.

“It is the most important species of fish; it carries energy and material from lower to higher trophic levels.”

Henrik notes that there are examples of wise management of other herring stocks that have been in a similar danger zone.

“But apparently, this does not apply to Sweden and Finland. I have been following this for 30 years now and saw in real time how the cod stock in the Kattegat was fished away despite our attempts to point out that this is going downhill. Two of the world’s most developed countries cannot take care of their common resource.”

Historical herring bans

“In the 1960s, there was a herring ban in Iceland, where fishing was more or less closed for about 30 years. It was so crucial to let the stock recover that they did not consider the fishing industry. Similarly, in the North Sea, fishing was closed in 1997. The British simply decided, ‘No, you cannot fish in the British zone.’ This led to the recovery of the North Sea herring.”

– Henrik Svedäng”

From the Finnish perspective, however, researchers seem satisfied with smaller quotas, not a fishing ban. In the parliamentary hearing, the Natural Resources Institute believed it was justified to set the total catch for herring in the Gulf of Bothnia according to ICES recommendations, in the range of 48,824 – 63,049 tons. The final quota set by the Council of Ministers was 55,000 tons.

“Since the current understanding of herring in the Gulf of Bothnia is limited, I believe the Council of Ministers’ decision was a sufficient compromise, as it now also aligns with the original recommendations from ICES,” says Katja Mäkinen at the Archipelago Research Institute at Åbo University, who has been researching herring in the Archipelago Sea and the Gulf of Bothnia for 40 years.”

Finnish researchers point to factors other than fishing

Both Katja and Jari point to other factors, such as climate change, eutrophication, and salinity, as more significant for the well-being and future of herring than the fishing industry.

“The best would be if we could reduce eutrophication and bring in more salt from the Atlantic,” says Jari.

“Herring has been noticeably affected by rising water temperatures and decreased salinity in recent decades. Temperature and salinity are the key environmental factors for biodiversity in the Baltic Sea, and they affect species indirectly through reduced food availability, for example, and directly through their impact on fish physiology,” says Katja.

She mentions that over the years in Finland, various factors have been discussed in relation to herring, ranging from pollutants and shipping to wastewater and industrial fishing.

“It is likely that all these factors have had an impact on the population, but larger trends and changes—such as the size of the herring—are more likely linked to issues affecting the entire sea, such as changes in temperature, salinity, and eutrophication.”

Ulf Bergström understands the concern for the general well-being of the Baltic Sea and the consequences it has for fish stocks but does not believe it is the right focus when it comes to herring.

“Of course, it affects, both eutrophication and climate change, but we can’t do anything about it in the short term. What we can do is manage the fishing take.”

Are they seeing the same fish?

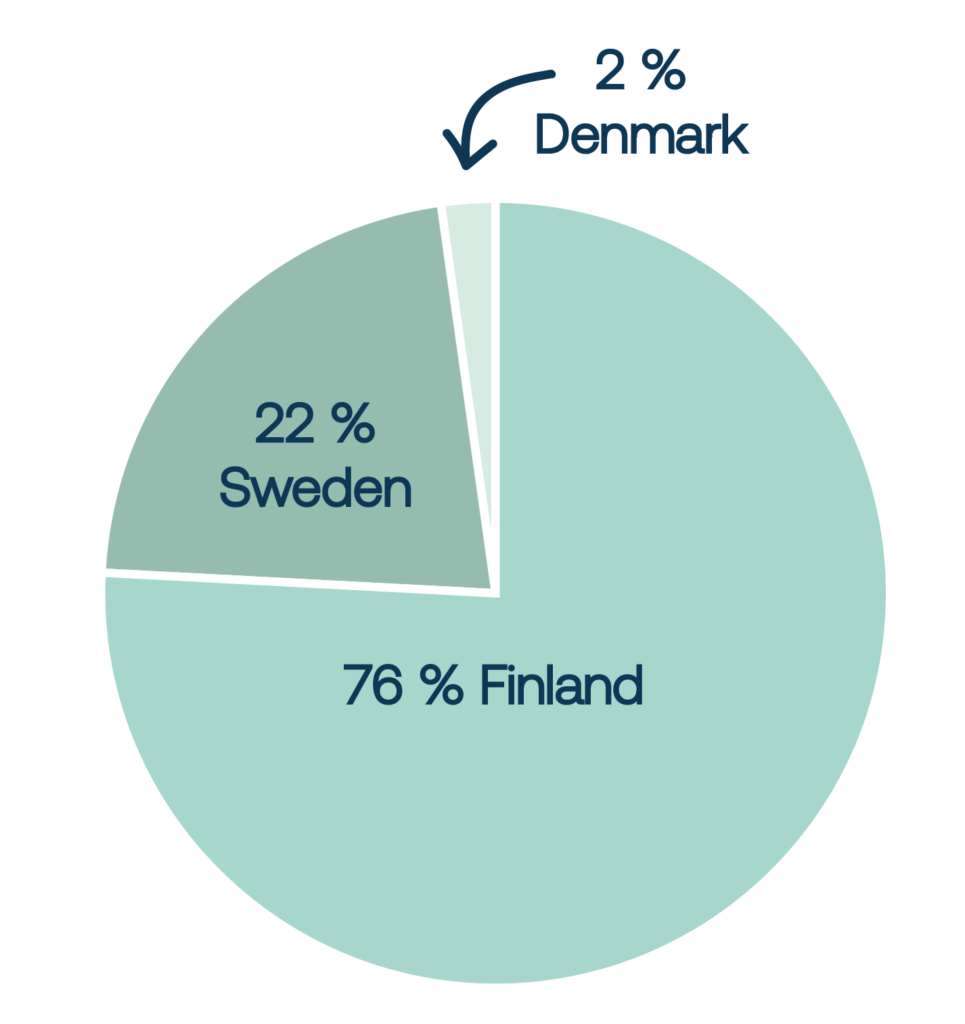

When it comes to extraction of fish, Finland actually has the greatest responsibility. The Finnish fishing industry accounts for the lion’s share of the catch in the Gulf of Bothnia. Despite utilizing only 60 percent of the allocated quota for the area last year, the catch was still substantial – about 60,000 tons. In Finland, the herring stock is perceived as healthy.

“Herring is abundant in Finnish coastal waters. Last spring, Finnish fishermen had good catches in the northern Archipelago Sea and along the coasts of the Gulf of Bothnia,” says Jari Raitaniemi.

In Sweden, on the other hand, herring is perceived as overfished.”

One theory that could explain the murky debate between the countries is that it may involve different subpopulations.

“It can be as simple as we are not looking at the same fish. The status of the stocks is perceived differently, and we may be observing different trends that may not be as clear along the Finnish coast. The different subpopulations may be different in terms of productivity and the extent to which they are exploited,” says Henrik Svedäng.

This reasoning is supported by research at Uppsala University, where they have mapped the entire genome of herring in the Atlantic and the Baltic Sea. Leif Andersson, with colleagues, has found that there are as many as 15 million genetic variants in the herring stock and that there are subpopulations that have adapted to local conditions.

“Yes, that is a possible explanation for why the fishing quantities are perceived differently in both countries. We know that we have many different subpopulations in the Baltic Sea, based on the analysis of spawning fish, but we have almost no knowledge of where the different populations are outside of spawning. So, it is possible that the populations spawning along the coasts of the Gulf of Bothnia have been particularly heavily exploited by industrial trawling.”

The reasoning of the working group

Regardless of the factors causing the lack of consensus, both Finland and Sweden are part of the working group that jointly contributes advice to ICES regarding fish stocks in the Baltic Sea. This means that every year, they must agree on what should be included in the joint document. Ahead of this year’s quota decision, the Baltic Fisheries Assessment Working Group (WGBFAS), including Jari Raitanen from Finland, recommended a fishing ban in both the Gulf of Bothnia and the central Baltic Sea. Mikaela Bergenius Nord, a Swedish member and former chair of the group, says they had discussions where they were not entirely in agreement, but she perceives that consensus was still reached regarding the report and its interpretation of the multiannual plan for the Baltic Sea – that if the biomass has a 5 percent probability of being below the critical limit (Blim), the advice for targeted fishing should be zero.

“Of course, individual researchers afterward can say, ‘Well, I didn’t quite agree,’ and they have the right to do so. Still, we must stand united in what we submitted to the review working group,” says Mikaela Bergenius Nord.

The working group also describes in the document what the Finnish researchers highlight; that the herring starvation noted in 2021 probably resulted from a lack of food and that the improved condition observed in the winter of 2022-23 suggests an improvement in food availability.

“But if you look at the stocks as a whole, they have gone from a very high level to a very low level, even though it looks better now regarding herring’s food supply.”

Decisionmaking process within the ICES

The annual stock assessment results in a draft catch advice for the following year. This advice from the working group, including all the methodology and calculations behind it, is then reviewed by independent experts in a so-called Advisory Drafting Group (ADG). The ADG’s opinion is then forwarded to ICES Advisory Committee (ACOM) for final quality review and approval. ACOM consists of a permanent group of senior experts from member countries and is led by a chairman employed by ICES. In addition to this annual advisory process, regular reviews (3-5 year intervals or more frequent if needed) of knowledge and data foundations and methods take place in specific benchmark meetings. These aim to continuously improve and quality-assure the advice and determine which methods and data should be used going forward. The benchmark process is also scrutinized by independent experts.

Source: SLU

Jari Raitaniemi at the Natural Resources Institute says that fall surveys indicate an improvement in the herring stock, and according to him, the biomass in the Gulf of Bothnia should be above the Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY) threshold, the fishing pressure that can provide maximum sustainable yield in the long term.

“The situation looks promising.”

However, the next official stock assessment will only be conducted in the spring of 2024, forming the basis for the stock status in 2024 and catch recommendations for 2025.

“Before we conduct a new stock assessment, incorporating all newly collected, quality-assured, and analyzed data from 2023, we cannot confidently comment on any changes. Neither positive nor negative. What we have to rely on today is the stock assessment conducted in the spring of 2023, with data up to 2022. I certainly hope that the trends Jari talks about will positively impact the stock, but ICES has not tested this yet,” says David Gilljam at SLU, who participates in research trips from Sweden and focuses on the Gulf of Bothnia.

Events in advance?

Mikaela Bergenius Nord says she “sincerely hopes” that the Finnish researchers are correct regarding the positive trend in food availability, leading to better condition and increased biomass. However, she cautions against jumping to conclusions.

“The question is what risks one is willing to take when the stock is at this low level. I think ICES is taking too high a risk.”

She agrees with the theory that different subpopulations may lead Swedish and Finnish researchers to see the issue differently, but ICES does not currently take this aspect into account in its analyses.

“Unfortunately, we do not have that aspect in our analyses today. The different herring populations are managed as one large stock.”

Until more clarity is gained about the stocks, the precautionary principle should apply, according to Mikaela, meaning a significant reduction in the fishing quota or setting a zero quota for 2024.

“We cannot let herring and sprat go the same way as cod.”

Jari Raitaniemi states that there are no genetic studies on herring in Finland, but it is an interesting area for further research.

“Based on what I’ve heard from the Atlantic and what we’ve seen in the Baltic Sea, it seems that different populations of herring cannot thrive equally in the same environment at the same time. It is often said that there are different populations of herring along the Swedish coast and the Finnish coast, that they return to their own coasts to spawn. But I don’t know if there is genetic knowledge about how similar or different they are.”

Big industry in Finland

In Sweden, there seems to be a greater diversity in research on herring and sprat, with several universities and researchers conducting studies on these fish. Representatives from the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU) participate in research expeditions and represent the country in the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) working group. In contrast, Finland is represented by the Natural Resources Institute, a research and expert organization under the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. Previously, the same task in Sweden was handled by the Swedish Board of Fisheries, which was dismantled in 2011, and SLU took over the responsibility for calculating fish stocks for Sweden.

Naturresursinstitutet, LUKE (Luke), is an organization focused on developing solutions for sustainable and profitable use of renewable natural resources.

Key facts about LUKE:

Approximately 1,300 employees and 22 locations in Finland.

Engages in about 700 research projects annually, including around a hundred EU projects. Research constitutes about 70 percent of LUKE’s activities.

LUKE’s total budget for 2020 was around 125 million euros. Of the funding, approximately 60 percent came from state budget financing allocated through the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (JSM), about 35 percent from project financing from other sources, and an additional approximately 7 million euros from joint projects with businesses.

“There is a history within fisheries management that it has been politically driven, and there are still remnants of that in some countries around the Baltic Sea. That was also one reason why Sweden closed down the Swedish Board of Fisheries – fish research was in the same place as the administration, and then it became too close, so to speak,” says Ulf Bergström.

Can you fish nutrients out of the water?

There is a perception that the fishing of herring and sprat can contribute to reducing eutrophication in the sea. These fish contain approximately 2.4 percent nitrogen and 0.4 percent phosphorus. The total fishing quotas for herring and sprat for 2024 would thus correspond to a maximum extraction of 1440 tons of phosphorus and 8042 tons of nitrogen. This represents 5.4 percent and 0.9 percent, respectively, of the annual phosphorus and nitrogen input to the Baltic Sea. For Sweden’s quotas, this would mean a maximum extraction of 266 tons of phosphorus and 1485 tons of nitrogen, equivalent to 1 percent and 0.2 percent, respectively, of the annual phosphorus and nitrogen input.

When comparing these quantities with the total nutrient load in the Baltic Sea, approximately 700,000 tons of phosphorus and 6 million tons of nitrogen, it appears that the total fishing from Baltic Sea countries extracts a marginal amount of phosphorus (0.2 percent) and nitrogen (0.1 percent). It is important to note that this perspective does not take into account other aspects of the impact of fishing and the complexity of the eutrophication problem.

There is also a difference between the countries regarding the significance of the fish processing industry. In Finland, the fish farming industry is substantial, and there is a lot of talk from the state about promoting domestic nutrient cycles through herring fishing. On the website of the Natural Resources Institute, it is mentioned, among other things, that “If feed made from Baltic herring were used in the farming of rainbow trout, a large amount of nutrients would be removed from the Baltic Sea in connection with the catch of feed ingredients.” However, the argument that one can “fish out eutrophication” from the sea is rejected by many Swedish researchers BalticWaters has spoken to as irrelevant.

Ulf Bergström generally feels that there is a lack of critical discussion about the negative effects of fishing in Finland. He also criticizes Finnish media.

“In Sweden, there have been many critical examinations of fishing; the equivalent has not been as extensive in Finland. To make informed decisions about fishing, there needs to be a public debate, and Sweden certainly has that. We have debated and scrutinized this much more in Sweden than has been done in Finland.”

Discussions and collaboration between the countries are something that Finnish researchers also welcome.

“I’m sure most researchers would agree that there could be more of that,” says Katja Mäkinen at the Archipelago Research Institute.