The former Director General of the Swedish National Board of Fisheries 14 years after the introduction of ITQs: “I failed”

– Today, the extension of individually transferable quotas for the bottom trawl fishery is being investigated

Fourteen years ago, the system of individually transferable quotas (ITQs) was introduced for the Swedish pelagic fishery (fishing in the open sea). The system has been criticised and debated, but now the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management (HaV) is investigating the possibilities of extending it to include demersal fishing (bottom trawling). BalticWaters spoke to the founder of the Swedish ITQ system, the former Director General of the National Board of Fisheries, who today regrets his decision and calls for fisheries policy reforms to ensure sustainable fishing.

‘We need, in a more systematic way, to adapt capacity to what is available to fish. At the same time, we need to get new, young people into the fishery.’

These were the words of the then Director General of the National Board of Fisheries, Axel Wenblad, in an interview with TT in the autumn of 2006 about the ideas behind a change in fisheries management in Sweden. At the time, the Swedish Board of Fisheries had presented a proposal for fisheries reform the year before. This resulted in the introduction of annual quotas in 2007 and individually transferable quotas (ITQ) in 2009. But the result, in retrospect, was not what Axel Wenblad had hoped for.

– I believe I failed. I should have introduced barriers in a completely different way. We should also have made completely different demands on the responsibility of the fishing industry.

Became a referee

The move to individual quota systems was well-intentioned, he believes. The previous system had its flaws and a change was needed.

– When I started in 2006, the pelagic fishery had a two-week ration.

The ration system was introduced in 1995 for cod and extended in 2002 to include herring and sprat in the Baltic Sea. The aim of the rations was to ensure a controlled and steady supply of fish, but instead it turned into a race to catch the fish.

Axel Wennström. Photo: Private

Vessels competed to be the first to go out and catch as much as they could during the period. This led to a waste of resources as some of the fish had to be thrown away at the end of the ration period and the system was also not adapted to the processing industry’s schedule.

– The views of the fishermen and the processing industry did not coincide and I sat there as a kind of referee. I spoke to the fishermen and said ‘you can’t have it this way, we have to find another way’.

“The destructive economic incentives associated with open fisheries, total allowable catch (TAC) systems and non-transferable fishing quotas are well known to fisheries scientists and increasingly to policy makers and fisheries managers. Overfishing, fishing during inappropriate parts of the fishing season, lobbying for increased fishing quotas, by-catch discards and overall overcapacity are some key problems that have been identified and are directly linked to the incentive structure faced by fishermen in such industries.”

“The economics of the Swedish individual transferable quota system: Experiences and policy implications”

This gave rise to the idea, developed in consultation with the industry, of having annual rations instead. Introduced in 2007, annual rations allowed fishermen to decide when they wanted to go out, made it easier to adapt to demand and made fishing more profitable. Since 1995, fishermen had been struggling with poor economics, with a real low point in 2004.

– There was overcapacity in the pelagic fishery, which was quite large. So moving from two-week rations to annual rations would allow for a better distribution over the year and also reduce capacity and increase profitability – at least that was my idea.

But the industry pushed for more reforms.

– The quotas were tied to the vessels and then came the idea of making them transferable, says Axel Wenblad.

Rights-based system

Transferable, tradable fishing quotas, known as ITQs, have been used around the world since the 1970s, starting in New Zealand. The system is a type of rights-based management whereby a particular individual or group of individuals, in this case fishermen, are given exclusive rights to exploit a resource. RBM aims to address the ‘tragedy of the commons’, whereby a resource or stock is freely exploited by people who do not feel responsible for its long-term sustainability.

‘Rights-based management changes the economic incentives to make it worthwhile for individual fishermen to think more long-term,’ write Mark Brady and Staffan Waldo in their 2008 report ‘How to solve the fisheries crisis’. ITQs as a system give fishermen both the freedom and responsibility to manage the quota they have been allocated and to plan for the long term. It also allows for quota trading, which would make the fleet more cost-effective and reduce the problem of overcapacity.

– Overcapacity is something that has always been a problem in industrialised fisheries all over the world, says economist Staffan Waldo.

This was the reason why so many countries had already moved to the transferable fishing quota system by this stage. Sweden was inspired by Norway and Iceland, among other countries, and several studies had shown the socio-economic benefits of the system. However, it should be remembered that countries such as Iceland and New Zealand are in principle the sole quota holders in their waters – so there are also incentives for their fishermen to fish sustainably and carefully.

Iceland as a role model?

Many studies have been carried out on the advantages and disadvantages of ITQs. Sweden often points to Iceland as a model, where the ITQ system covers both pelagic and demersal fisheries and has made the industry more profitable. Iceland had problems with overfishing in the beginning, but an evaluation from 2022 shows that most stocks are now sustainably fished. However, ITQs are not popular with the Icelandic people, with opinion polls between 2003 and 2007 showing that between 70 and 80 per cent of the population were critical of the system.

Criticism on Swedish adaptation

Sweden’s departure from the classical model has been criticised by some researchers. They argue that it has reduced the socio-economic benefits of the ITQ system and removed some incentives for structural changes in fisheries management.

Source

In a statement of opinion sent to the Council on Legislation on 12 February 2009, the Government argues that a system of transferability based on voluntary participation would be a positive step in the development of Swedish fisheries policy. The draft law states that the purpose of introducing ITQ systems is to ‘promote a balanced vessel structure in the Swedish fishing fleet in commercial pelagic fishing so that it contributes to the conservation of fish resources and otherwise sustainable fishing’. However, Sweden departed from the classical model on a number of points, including the fact that fishing rights had a time limit of 10 years.

Should have put on the brakes

After the law was passed in spring 2009, negotiations between the Swedish Board of Fisheries and the fishing industry remained on the practicalities before the new system became a reality in autumn 2009.

– Above all, we discussed how we would base the quotas we would receive, says Axel Wenblad.

He was not physically involved in the discussions himself, but they were handled by representatives from the National Board of Fisheries.

– The fishermen were represented by Reine Johansson, explains Axel.

Reine Johansson…

… was a Social Democrat and a skilful lobbyist who, among other things, was head of the Swedish Fishermen’s Association. He played an important role in fisheries policy for many decades. His importance in the development of the fisheries we have today is colourfully described in a report in Icon magazine: ‘There has been a rumour going around for many years that I have only recently had confirmed to me, namely that Reine was so often at the Swedish Board of Fisheries – where his trademark was to scold administrators and middle managers and put the fear of God into them – that he was given his own desk there,’ says Markus Lundgren, head of the Western region of the Swedish Sport Fishing and Fisheries Conservation Association.

According to Axel Wenblad, the negotiations with the industry ended with everyone being ‘very satisfied’. He stayed at the National Board of Fisheries until 2011 and says he did not notice any negative effects of the reform during those years. But as time went on, the industry started building bigger boats to make fishing more efficient, and the industry became increasingly concentrated in a few players with bigger and bigger vessels.

– I had not thought of that. We should have set limits on how big the boats could be. We should have capacity in relation to the stocks. We are now in a disastrous situation in the Baltic Sea as regards fishing for herring. Actually, the brake should have been put on several years ago.

In addition, since the introduction of transferable fishing rights in 2009, the proportion of fish for human consumption has fallen drastically in favour of large-scale industrial trawlers fishing for feed.

From 81 vessels to 41

When the system of transferable fishing rights was introduced in November 2009, 81 vessels had pelagic licences. In autumn 2016, the number was down to 41. Interviews with stakeholders in the investigation also revealed that fishing rights were expensive, as much as SEK 79.9 million (although the figures were disputed by the industry). In 2022, the 20 largest vessels caught 95 per cent of the fish in the Baltic Sea.

Was that something you thought about when you were designing the scheme – what happens if a resource becomes depleted?

– My idea, and it was obviously not a good one, was that the industry would take responsibility for the resource. But they fish as much as they can and some of them also cheat. It was completely misconceived that they should take responsibility.

But could boat size limits have been introduced and would that have helped the problem? Staffan Waldo is sceptical.

Staffan Waldo. Photo: Private

– I don’t know that it would be done anywhere else, it’s possible. But then you are back in the old types of regulations. There are many funny pictures of people who have managed to circumvent these regulations. You have boats that are perhaps exactly 9.99 metres when the limit is 10, or they have cut off the bow… We also have technology that is developing all the time, which makes it difficult to keep up and adapt regulations.

But on the other hand, we could have been wiser and learnt more from other countries‘ experiences with ITQs before introducing them in Sweden. In 2016, economics professor Jesper Stage wrote a scientific article together with two research colleagues in which they identified several pitfalls that could have been avoided in the transition to the new fisheries policy, including how to design the system so that it would be easy to follow up economic and biological consequences.

– The picture we got was that this was something that many other countries had done, but they hadn’t looked very closely at why it worked or didn’t work.

In their overview study, they also refer to issues raised when the law was drafted that were not taken seriously. For example, it was unclear how transferable fishing rights or fewer vessels would automatically lead to reduced fishing pressure or sustainable fishing.

– The government simply replied that it was obvious. But if fishing is not sustainable, it doesn’t matter in the long run how you allocate fishing rights. Biology should be taken more seriously and should have been all along. ITQs are an efficient way to allocate resources, but the total size of quotas should be based on biological research.

There are other rights-based models that could have been used instead of the ITQ model, but according to Mr Waldo, ‘there are no perfect systems’. He also emphasises the importance of biological advice being followed.

Jesper Stage. Photo: Private

– It is very important to have functioning scientific advice and that politicians make the right decisions to maintain biodiversity.

But then fishing must also be better monitored so that quotas are not cheated.

– This is an issue we didn’t write about in 2016, because we didn’t realise it then – that we have little control over how much is being fished. There are fishermen who fish one species and report something else. Then a system like this becomes meaningless. But that’s what seems to have happened in practice, says Jesper Stage.

Timeline for the introduction of transferable fishing rights.

Speaking up for herring

Axel Wenblad, who has been called the ‘father of the quota system’ in Sweden, says he realised the problems in fisheries management a few years ago. At the time, he was chairman of the WWF, a post he held for 9 years after leaving the National Board of Fisheries. Today he does not mince his words in the hope of correcting the problems he has partly helped to create. Last autumn, he spoke out about herring ahead of negotiations in the Council of Ministers on fishing quotas.

“The government has been passive, not least during the spring when Sweden held the presidency of the EU and thus had a great opportunity to influence our neighbours. The large-scale trawling industry has not shown any responsibility for the long-term development of herring stocks.”

Axel Wenblad wrote this in an opinion piece in Svenska Dagbladet in September 2023.

In the piece, he suggests ways forward, including moving the trawl limit, introducing a temporary ban on large-scale trawling with the other EU countries around the Baltic Sea and ensuring that the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management can effectively control large-scale fishing for herring. He fears that herring will go the same way as cod.

– There is no cod fishing in the Baltic Sea today. We have driven one species to the bottom, now we are about to drive another one to the bottom.

After his time at WWF, he became chairman of the Baltic Salmon Foundation last year.

– The one-liner I use there is ‘no herring, no salmon’. If the salmon are also driven to the bottom, then we have succeeded with three species: cod, herring and salmon.

He notes that long-term thinking is lacking in both politics and the industry.

– It’s shameful.

Enquiries for demersal fishing

At present, the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management is investigating the possibilities of broadening the system of transferable fishing rights to include fishing for demersal species. Species included in the fishery include Norway lobster, North Sea prawn and cod. The mission must report by 1 April 2024.

– I strongly advise against this. We should first learn why things turned out the way they did, says Axel Wenblad.

Studies of the system have been carried out – both in 2014 and 2016. The latter report concludes that the aim of improving profitability in the industry has been achieved, but that it is ‘unclear whether fishing has become more environmentally and socially sustainable’. But Jesper Stage says the system was designed in a way that makes it impossible to really evaluate, especially when it comes to the economic side. What he means is that the prices at which the quotas are sold have remained secret.

– It was something that some of my students talked to HaV about back then in 2010, we said that there will be problems.

The answer they got was that it was not possible under the law to require disclosure of sales prices.

– But then the law could have been changed. It would have made everything more transparent if the prices had been clear.

Could this be changed before introducing the system in demersal fisheries?

– Yes, and it would not be a big deal, that you need to report to the authority. I don’t see why it should be so sensitive.

He also believes that greater financial transparency would have favoured the smaller players in the market.

– Many of the small-scale fishermen probably didn’t realise how valuable the quotas were in the beginning and sold them too cheaply.

What is the situation in Finland?

In 2017, Finland introduced the ITQ system, which has led to large parts of the fishing industry ending up with owners outside Finland, mainly Estonia. 60% of the largest vessels were owned by Estonians in 2020. A review by the public service broadcaster Svenska Yle reveals criticism from domestic local stakeholders. There is no distinction between fishing for food and for feed and new fishermen find it difficult to break into the industry.

‘They looked at the catch history five years back in time. For us, who have focussed on quality, this meant that we had quite a small catch history. This meant that we were granted little utilisation rights as well,’ says Anders Granfors of Sonnskär, one of the largest Finnish-owned trawlers that focuses on catching food fish. Sonnskär’s quota has often run out in spring or summer, and the company has then had to rely on rental quotas, making it difficult to plan ahead. In Finland, it is secret who is allocated catch quotas and how large these quotas are.

The draft law submitted by the Finnish government to Parliament on 16 June 2016 states: “In the future, private operators will bear the main responsibility for the utilisation of fishing quotas. This will enable operators to optimise their activities according to market needs. At the same time, it will improve the opportunities for profitable business growth, co-operation across the value chain and the development of new high-value products. For example, in Sweden and Estonia, a similar system has led to a significant improvement in the profitability of the sector.”

As part of its current mission, HaV is interviewing researchers and experts, including economist Staffan Waldo. His advice for a successful system for demersal fisheries is to ‘hold your tongue from the start’.

– What is it that we want and achieve? It’s hard to change afterwards when you realise things have gone wrong.

Jesper Stage says it feels like more careful preparations are being made this time than in 2009.He himself, together with a research assistant, has been involved in producing one of several reports commissioned by HAV.The report Stage has helped to produce is about what HAV should acquire more information about.

– It is mainly price information that we consider to be the big gap.

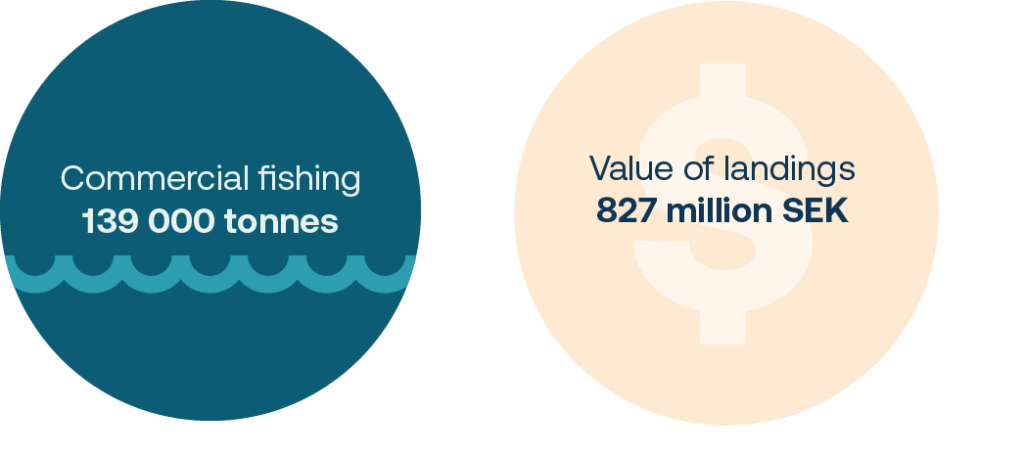

139 000 tonnes, that’s how big commercial sea fishing was in Sweden in 2022. The value of the landings totalled around SEK 827 million. Source: SCB

‘Still in doubt’

The HaV’s website states that the proposal will include maximum holdings of individual fishing rights as well as special measures to facilitate the establishment of new businesses to address some of the problems identified in the pelagic fishery. Axel Wenblad does not know if this is enough.

– I’m still not sure. Firstly, there should be a proper evaluation of what happened to the pelagic – a critical evaluation. Can we avoid falling into those traps? How do you get the industry to take responsibility for the resources? How do you get rid of cheating? he asks.

What would you do if you had to do it all over again?

– I would have introduced barriers in a completely different way. And then I would have made completely different demands on the fishermen’s responsibility.

He also questions the decision-making process in EU fisheries management.

– It shouldn’t be the case that first ICES, then the Commission, and then a bunch of ministers come along and say “this is how it’s going to be”. I’ve been involved in fisheries negotiations and I’m not very impressed with the knowledge and ability of ministers. We should consider whether we should not have expert decisions on such things.

BalticWaters comments:

Any extension of the system of transferable fishing rights should be done carefully and only after extensive evaluation and revision. Given that benthic species such as cod and Northern prawn are red-listed, it would be wise to prioritise measures to first achieve sustainable fish stocks before further developing the quota system. If there are no fish, there will be no quotas to sell or manage. It must also be emphasised that the overall ambition of the system – to make fisheries feel responsible for the resource – has completely failed. Over the last 15 years, virtually all of the Swedish medium and small-scale fisheries have been wiped out in favour of a few large industrial trawlers, which also have an absolute majority of the quotas. There are many reasons why large fish, such as cod and herring, have gradually been wiped out in the Baltic Sea, but overfishing and poor control have been factors that could have been influenced by both responsible authorities and politicians.