Since 2022, BalticWaters has supported research that contributes to the knowledge required for a healthier Baltic Sea. One of the first projects to receive funding was Increasing the knowledge of herring and sprat, where researchers investigated the age and longevity of these two important species. The project has now ended, and we’ve taken a closer look at the results – and how they can be used in the future.

To make informed decisions about fishing in the Baltic Sea, we need to know the age structure of fish stocks. A healthy stock has a broad age distribution, with enough sexually mature individuals to reproduce. However, if the stock lacks older individuals, it may be a sign of overfishing or other ecological disturbances.

The methods used to age fish may not have been able to deliver reliable results – something that Francesca Vitale and Allen Hia Andrews, researchers at the Department of Aquatic Resources at SLU Aqua, wanted to change.

– We have a lot of knowledge about the age structure of herring and sprat, the problem is that the knowledge is based on assumptions that the counting method is correct, they say.

To investigate the issue further, the researchers launched a two-year project in 2022 with support from BalticWater’s program to fund research projects and pre-studies, with the aim of establishing a new, more reliable method for assessing the lifespan and growth of herring and sprat in the Baltic Sea.

Nuclear bombs play an unexpected role in age determination of fish

A commonly used method for age determination of fish is to count growth rings on their otoliths. Using this technique, it has been estimated that herring and sprat in the Baltic Sea can live to be over 20 years old, but it has been uncertain whether each ring really corresponds to a year. So, to test the reliability of the method, Francesca and Allen turned to a somewhat unexpected time-specific marker – radioactive traces from nuclear tests.

The method, called bomb radiocarbon (carbon-14) dating, is a proven technique for determining the age of fish and other aquatic organisms, but has never been used in the Baltic Sea. The method is based on the radioactive traces left in nature after nuclear weapons tests in the 1950s and 1960s. These tests released carbon-14 into the atmosphere – a signal that was then taken up by plants and animals. The signal is visible in the otoliths of fish, for example, and acts as a timestamp in their growth.

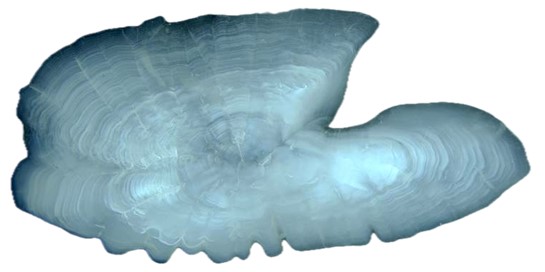

Close-up of an otolith from a Baltic herring. Photo: Yvette Heimbrand.

The radioactive signal in the environment is compared with the signal in the fish’s otoliths

Previously, the sharp increases in carbon-14 from nuclear testing have been used as a reference by matching the signal in the fish otoliths with the carbon-14 curve of the environment where the fish grew up. However, this means that the method can only be used for fish that are currently over 50-60 years old – and that it will eventually become unusable.

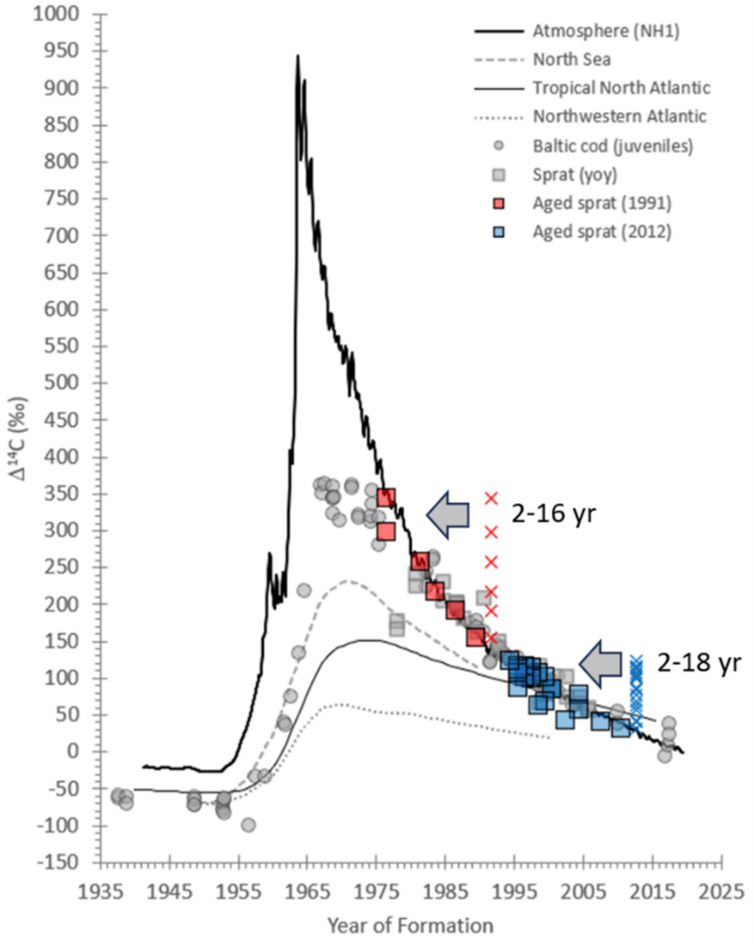

To determine the age of herring and sprat, Francesca and Allen have instead utilised the gradual decline of carbon-14 that followed the nuclear weapons tests. By comparing growth rings with the carbon-14 signal in otoliths from fish with known birth years, they have created a reference curve for the decreasing carbon-14 levels in the Baltic Sea region. This curve can then be used to age other fish by comparing the carbon-14 levels in their otoliths with the expected values for their estimated birth years.

How fish age is determined using carbon-14

Nuclear bomb tests in the 1950s and 1960s caused a sharp increase in radioactivity (carbon-14) in the Baltic Sea. Initially, carbon-14 levels rose due to runoff from land into the sea, but over time, the concentration began to decline. This created a curve with a rise, a peak, and a gradual decrease in carbon-14 levels in the Baltic Sea.

By analyzing otoliths from herring and sprat collected in previous years (archived samples) and measuring carbon-14 activity at different catch years, the researchers have created a curve that reflects environmental changes in the Baltic Sea. This has allowed them to establish a reference curve linking catch years to carbon-14 concentrations. Each fish (otolith) represents the total carbon-14 concentration accumulated over its lifetime and the specific years it lived. Using this reference curve, researchers can then place “unknown” fish otoliths on the curve and determine the fish’s age and catch year by measuring the carbon-14 concentration in the otolith.

In the figure, carbon-14 levels in the otoliths of sprat (2–18 years old) are compared with the reference curve for carbon-14 levels in the environment. The age of the sprat was first estimated by counting the growth rings in the otoliths. The age was then confirmed by “matching” the carbon-14 levels in the otoliths to the expected levels for their estimated hatch year on the reference curve.

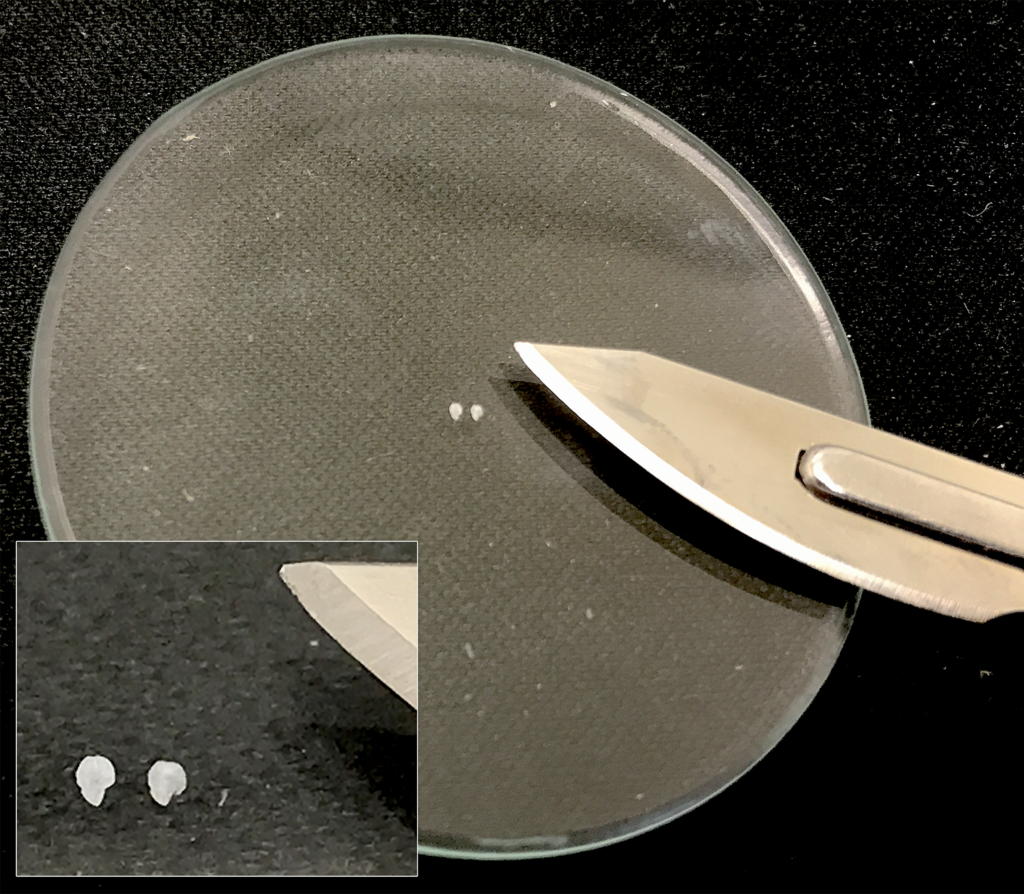

Two sprat otoliths next to a scalpel as a reference to illustrate how small otoliths can be. Photo: Allen Hia Andrews

Accurate age determination can improve management of more species

Through the establishment of the new reference set for the Baltic Sea region, Francesca and Allen have been able to validate previous knowledge about growth and maximum age in herring and sprat in the Baltic Sea. This is an important result for reliable stock assessments and long-term sustainable fisheries management.

– To determine sustainable catch levels, the age at which fish become sexually mature and the number of years they can reproduce are usually considered. If these characteristics are incorrectly assessed, catches may be too high, jeopardising the population’s ability to recover, write Francesca and Allen in their final report to BalticWaters.

But the project’s findings go beyond herring and sprat. A key part of Francesca and Allen’s work has been to establish a reference chronology of the carbon-14 signal for the Baltic Sea region, which now enables studies of more species in the region where knowledge of age and growth is lacking.

– The study’s early results have attracted interest, both in Sweden and other Baltic Sea countries, as the method could be used to analyse existing otolith archives of other fish populations facing long-term challenges, Francesca and Allen write.

– The results allow for more informed fisheries policy decisions, as the information on the life history of the species can be determined with greater certainty, the researchers conclude, and we need people to conserve any valuable otolith archives because sometimes they are thrown away.

The project Understanding the life histories of small pelagic fishes for knowledge-based management decisions and a healthier Baltic Sea environment is being carried out by the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. Through BalticWater’s program to fund research projects and pre-studies, the project was granted funding of SEK 991,900.

Want to know more about the project?

Take a look at Allen’s presentation on the project from the 7th International Otolith Symposium in Chile – you can find it here. You can also see a presentation from a conference in New Caledonia here and a seminar held at SLU Aqua here.