In August, the European Commission presented its proposal for next year’s fishing quotas in the Baltic Sea. After decades of heavy fishing pressure from the industry, scientific models proving wrong, and alarms about the decline of the herring population, the Commission is now proposing to stop all directed fishing for herring in the central Baltic Sea and the Gulf of Bothnia. The multi-annual management plan for the Baltic Sea, which is part of the law (Common Fisheries Policy, CFP), actually requires it.

The proposed closure of the directed fishery is timely. Herring stocks in the central Baltic Sea and the Gulf of Bothnia have declined drastically, the fish are smaller and growing slowly. Both stocks are close to or below a threshold called ‘Blim’. If a stock falls at or below the Blim, there is a high probability that the stock can no longer recover. The Baltic cod stock, which collapsed in 2019, still shows no signs of recovery, which is reflected in the proposal for a continued 0 quota.

The size of the western spring-spawning stock of herring remains below safe biological limits, so for the fifth year in a row, the Commission is proposing to close the fishery. Also new this year is the proposal to abolish the derogation previously granted to small-scale coastal fisheries.

Overall, the policy faces a very difficult situation. The biological reality is that herring populations, along with other species such as cod, have been fished to unsustainable levels. At the same time, calls for derogations for various fisheries have started to emerge. Is 2023 the year when Baltic Sea fishing, and fish, ran out?

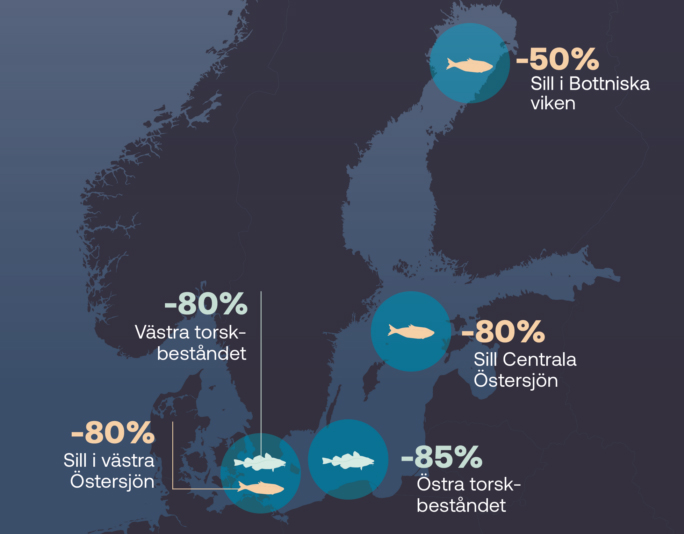

Illustration: Sill i västra Östersjön = Western herring; Västra torskbeståndet = Western cod; Östra torskbeståndet = Eastern herring; Sill i Centrala Östersjön = Central herring.

In the central Baltic Sea, herring stocks have declined by over 80 per cent compared to the 1970s. In the last four years, the stock has declined by 40% and is now at a critical level.

In the Gulf of Bothnia, the herring stock has declined by over 50% since the early 1990s.

In the Western Baltic Sea, herring stocks have declined by over 80% since the early 1990s. Read more about the development of herring and cod stocks at https://balticwaters.org/faktabanken/bestandens-utveckling-over-tid/

How did we get here?

There are many reasons for the decline of fish stocks – climate change and eutrophication are commonly mentioned, but no single activity has caused as much mortality as fishing. This is why failures in management and policy are so devastating:

- Uncertain scientific advice that has too often overestimated fish stocks (both cod and herring).

- An intensive industrial trawl fishery that fishes for feed at the expense of a small-scale, more low-impact fishery for human consumption.

- A very poor application of control in fisheries leading to cheating and misreporting of catches. The result is large amounts of inaccurate data in scientific modelling, which in turn leads to inaccurate stock assessments.

- Political decisions that for decades have put socio-economic considerations ahead of the Baltic Sea environment and the condition of the fish.

A fishing ban does not necessarily mean that the fish will stay in the sea

The large-scale trawl fishery for sprat comes with inevitable by-catches of herring and Baltic herring, as well as cod and salmon that follow the herring and sprat shoals in search of food. To better understand and assess the situation, the Commission has requested more data from the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES). This knowledge is needed to enable the Commission to assess the effects of by-catch in different fisheries. It is currently unclear whether ICES will be able to deliver the data in time for the Council of Ministers meeting.

Henrik Svedäng, a researcher at Stockholm University’s Baltic Sea Centre, writes that ‘by-catch quotas risk becoming a Trojan horse’. The herring and sprat fisheries are described as mixed fisheries, where it is difficult to fish one species without risking the other. If a sprat fishery is allowed, where a by-catch quota of herring is allocated, the closure of the directed fishery may lose its effect.

At the same time, control of large-scale sprat fishing is non-existent. It is the captain who writes in his logbook what is in the catch, something that has been shown to be poorly correlated with reality, as shown in our review Improper and fraudulent fishery – a threat to the Baltic Sea. If a by-catch quota is to be allowed, the application and control of large-scale fishing must be significantly tightened. Penalties must be severe and controls must be carried out on what is actually in the catch. Modern technology enables this, such as eDNA tests.

Henrik Svedäng tells Dagens Nyheter that large-scale sprat fishing should be stopped, due to the lack of control, something that we at BalticWaters believe is a necessity.

Targeted quota or by-catch quota for small-scale coastal fisheries?

SVT reports that voices are being raised in favour of targeted quotas, and that by-catch quotas for herring should go to small-scale fishing instead of large-scale forage fishing. The control of small-scale fisheries is better and it is easier for a smaller fishing boat to target one species without risking extensive by-catch of another. It’s an appealing measure that would help coastal fishermen survive the difficult situation we are in now – but what happens when all the countries around the Baltic Sea make the same demands in their respective fisheries? The sum of these quotas will affect stocks and thus jeopardise the recovery of herring.

Whatever the way forward, no by-catch should be given to the industrial feed fishery as it risks permanently destroying the herring stock.

An complex dilemma – crafted by politicians

Politicians have put themselves in a very difficult position. The question is whether the Member States and the Council of Ministers will respect and comply with the law (CFP) and management plan they themselves voted through?

The Minister for Rural Affairs, Peter Kullgren, has not yet commented on the Commission’s proposal. His press secretary told DN that it will be ‘… analysed according to the usual procedures. We will have to come back later’. A lot of work will be required by the ministry and the authorities to resolve the conflict between quotas for by-catches in industrial fishing and the needs of small-scale, coastal fishing.

The representative of industrial fishing, the CEO of the industry organisation Pelagikerna, Anton Paulrud, told DN that ‘…the herring is repressed, but not so repressed that you need to kill the whole fishery.’ This is the same argument that was used about cod, until fishing was completely stopped in 2019. Unfortunately, it is an argument that responsible ministers in both Sweden and the rest of the EU have listened to.

In Sweden’s case, it is the twenty largest trawlers that account for 95 per cent of Swedish catches in the Baltic Sea. Industrial fishing is not an important industry because processing takes place abroad when the industrial trawlers land their catches in Denmark.

Public opinion in Sweden has emphasised small-scale, coastal fishing for human consumption. A fishery that involves small catches compared to industrial fishing, but which means a lot to many small towns and fishing harbours. If the Council of Ministers decides on a zero quota, it means that this fishery must also be stopped.

If Sweden pushes for a smaller quota for coastal fisheries, it is likely that a number of other countries would do the same and industrial fisheries would demand a quota for by-catches. Such a decision is likely to be in breach of the law and would lead to such large removals of herring that the stock is likely to be devastated.

What can Rural Affairs Minister Kullgren and his colleagues do in the run-up to the October Council of Ministers?

- A drastic alternative is to stop large-scale industrial fishing of sprat. Such a decision would avoid by-catches and misreporting of herring. It could also create the conditions for a less targeted quota for small-scale fisheries fishing for human consumption.

- Swedish representatives must be much more active in contacts with other herring fishing nations already now. ‘Analysing according to established procedures’ must not take too long.

- The Minister for Rural Affairs and his colleagues must talk to representatives of the herring fishery along the entire coast, not just those dominated by industrial fishing interests.

- Sweden has failed to introduce effective controls on fishing. This is where the Minister for Rural Affairs can act quickly and forcefully – if there is to be a fishery in 2024, there must also be ‘order in the fishery’.

In the longer term, however, the challenges remain very high and will require major sacrifices from all parties involved. It is a situation that requires reflection and political courage. But when the fish are gone, they are really gone. Perhaps it is the case that fishing must be stopped today, if we want fishing to be possible tomorrow.

One thing is certain – in autumn 2023, Minister Kullgren faces difficult decisions – will he save the fishery or the fish?

Peter Kullgren. Photo: Ninni Andersson/Regeringskansliet

The European Commission’s proposal

| 2023 | 2024 | |

| Stocks and ICES advice by area (fishing zone) | Agreement in the Council of Ministers (in tonnes, % change compared to 2022 quota) | Commission proposal (in tonnes, % change compared to 2023 quota) |

| Western cod 22 – 24 | 489 (0 %) | PM (pro memoria). Quota will be proposed later |

| Eastern cod 25 – 32 | 595 (0 %) | PM |

| Western herring 22–24 | 788 (0 %) | PM |

| Bothnian herring 30–31 | 80 074 (-28 %) | PM |

| Riga herring 28.1 | 45 643 (-4 %) | 36 514 (-20 %) |

| Central herring 27–28.2, 29, 25, 32 | 61 051 (-14 %) | PM |

| Sprat 22 – 32 | 201 554 (-20 %) | PM |

| Plaice 22 – 32 | 11 313 (+ 25 %) | PM |

Key dates autumn 2023

- End of September: ICES delivers additional advice to the Commission and Member States

- 23-24 October: EU fisheries ministers decide on 2024 quotas

- December: Setting of next year’s quotas