Put simply, dredging is a fight against natural change. Land uplift causes the bay’s inlet to become too shallow for recreational boats to enter and exit the bay, and organic material accumulating on the seabed causes bathing sites to become shallower – by dredging we can restore the bathing site and the inlet to the bay. However, dredging has effects that can be difficult to predict, both at national and local level.

The project Thriving bays sees the effects of dredging

Researchers within the project Thriving Bays are examining and evaluating methods to reverse the negative environmental development of shallow bays caused by eutrophication, physical disturbance, and food web changes. During a period of two years, researchers studied numerous bays along the coastline, and in the summer of 2022, four shallow bays were selected as demo bays. All the demo bays have been dredged at some point in time, and the researchers found that dredging in the inlet of these bays has caused adverse long-term effects that are still evident many years later.

Emil Rydin, Associate Professor in Limnology, seems pensive when I question whether dredging should be done in the Baltic shallow bays.

”The solution is not to exclude people from the environment, the solution is to find ways where people can utilize and enjoy the coast with as little negative impact as possible,” answers Emil after a moment of silence.

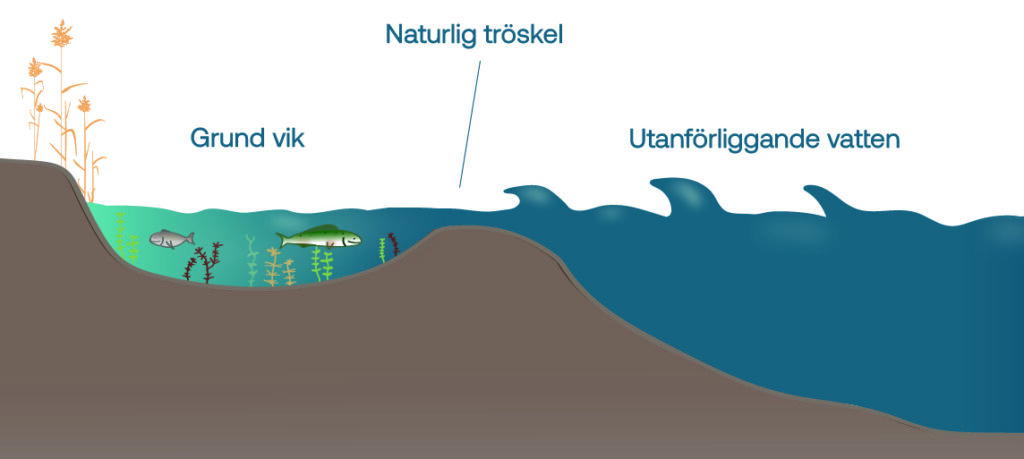

And he is of course right. Land uplift and sedimentation diminish the openness of the bays to external waters over time. The bays transition from open bays, with one or multiple mouths, to being more enclosed and isolated from the sea outside. Oftentimes, this is where dredging comes into play. By removing sediment and vegetation, or by moving rocks, , the mouth of the bay is kept open so that boats can enter and leave the bay. The shallow bay doesn’t follow the natural transition of turning into a cut-off bay and eventually a wetland; rather, the bay remains a bay. But what effect does this have on the environment? To answer that, we need to take a closer look at the distinctive traits of a shallow bay.

An abundance of life

Shallow bays are one of the most biologically rich environments in the Baltic Sea costal area. They consist of a shallow area that has been cut off by land uplift via islands, isthmuses, or shallow sill at the mouth of the bay. This isolation protects the bay from waves and strong water movements, causing the water in the bay to remain for a longer period of time, ranging from a day to over a month. The limited water exchange with the surrounding sea, in combination with the relative shallow nature of the bay, often with an average depth of less than three meters, causes the water to warm faster than the surrounding water. Because the water is still, sedimentation and an accumulation of nutrition-rich organic matter occur on the sea bed. This makes the bays very productive, with many different species of animals, algae and plants. Sunlight normally reaches the shallow seabed, allowing abundant vegetation to grow. Healthy vegetation in bays binds the soft bottom sediments, absorbs nutrients from the water, reduces turbidity and provides clearer waters. They also contribute with more organic material to the seabed as they decompose.

Dredging wounds can leak nutrients and cause turbidity

”Today, it’s difficult to find shallow bays along the Svealand coast with their natural sill intact,” says Emil who, within Thriving Bays, is researching the role of sediment on the well-being of the shallow bays. And sediments do indeed play a major role in the environment of the bay when the sill is dredged.

When the sill is lowered and the water depth increases, more water flows over the sill and the water currents then have erosion forces that cloud the water flowing into the bay. The turbidity blocks sunlight from the vegetation on the sea floor, and the particles that accumulate on the vegetation prevents the plants from photosynthesizing. This effect is interesting because dredging has historically been used as a method for opening bays to increase water exchange to improve water clarity – but it can rather have an opposite effect.

”In one of the demo bays, Högklykeviken, we see ongoing erosion on satellite images ten years after dredging has occurred. Prior to the dredging, there was a rich plant and animal life in the bay, today the water is turbid with little vegetation and fish,” Emil says.

Another effect of dredging is that nutrients, in the form of phosphorus, can be released from the sediments.

”In shallow bays along the Svealand coast, there is generally a lot of easily accessible phosphorus a bit deeper down in the sediment layers. When dredging, this sediment layer can be exposed and the phosphorus can be absorbed into the water mass and drive the growth of phytoplankton

Different bays – different effects of dredging

Joakim Hansen, environmental analyst with a focus on benthic vegetation and benthic animals at Stockholm University Baltic Sea Centre, points out that the effects of dredging varies between different bays.

”We need to increase awareness about dredging and how it affects shallow bays depending on their characteristics. For example, in a bay with coarse sediment, dredging will not cloud or release as much phosphorus as in a bay with muddy, nutrient-rich sediment. We need new knowledge to provide tailored recommendations for different types of environments,” Joakim remarks.

However, the consequences of dredging the bay’s sill are not to be ignored.

”When the sill is lowered, water exchange with the sea outside increases, causing the water movement in the shallow bay to increase and the water temperature drops. The calm, warm shallow bay no longer possesses the same conditions to function as a nursery for animal and fish species during spring and summer,” says Joakim.

At the same time, there are large dredging projects that have been successful, Joakim emphasises. However, the projects have to be well planning and well execution to prevent particles and nutrients leaking from either the dredging area or the dredged material.

”What we see within Thriving Bays is the opposite — small-scale dredging operations have had huge negative consequences locally. If these small-scale interventions occur in many places along the coast, consequences will no longer only be evident locally,” Joakim points out.

Oscar Törnqvist works at the Geological Survey of Sweden (SGU) where he maps physical disturbances in marine environments along the Swedish coastline, among other things. Oscar highlights that the impact of dredging depends entirely on the natural environment.

”In archipelagic environments, where the seafloor and shoreline consist of clay, very large problems arise with turbidity that often spread over long distances and that can reoccur for many years, which affects bottom vegetation and animal life negatively. In more gravelly coasts, which predominate in the Bothnian Sea, the Bothnian Bay, and the south of Västervik, turbidity problems do not arise in the same manner. Here, the problem is foremost the loss of the shallow bottoms, which has major consequences for macro vegetation and coastal spawning fish such as whitefish,” says Oscar.

What is the solution? How can we maintain the natural environments in the shallow, sheltered bays, while allowing people to use and live along the coast?

There is little research on the effects of dredging in a larger context; however, Oscar points out that studies of satellite images provide a clear picture of how anthropogenic turbidity dominates protected archipelagio environments where clays in the seabed and shoreline are common.

”Permits, supervision, and measures should take local conditions into account,” Oscar maintains.

SGU is currently collaborating with the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management (SwAM) to develop a risk map for turbidity problems, as part of the national strategy against physical impact and the action plan for the marine environment 2022-2027 according to the Decree relative to protection of the marine environment.

In the case of the demo bays, Joakim, Emil, and their researcher colleagues will investigate solutions that enable the bay to have a suitable threshold, while allowing boats to easily pass in and out of the bay. This would protect the bay’s natural environment, while allowing residents to use the bay as they do today. This is a step in the right direction to develop new knowledge both about dredging and its effects, but also about appropriate measures to reduce negative effects. However, there is a lot of work remains to be done. One thing is certain: if we tamper with the conditions in our shallow sheltered bays, they will change in ways that are difficult to predict.

What are the rules for dredging?

The rules for dredging are far from comprehensive. Large-scale dredging requires a permit, while small-scale dredging only needs to be reported.

From the SwAM 2018:19 directive Dredging and management of dredged material:

Sid 71: Page 71: In running watercourses a notification requirement applies to dredging where the bottom surface covers a maximum of 500 square meters. Bodies of water other than watercourses are also subject to a notification requirement as long as the bottom surface amounts to a maximum area of 3000 square meters. If the dredging concerns a larger area, a permit is required.