New analyses from the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) show continued worrying trends for several commercial fish stocks in the Baltic Sea. Sprat recruitment has never been as low as in the last three years, cod shows no signs of recovery, while the advice for herring in the central Baltic is baffling. This year, a great responsibility rests with our politicians – their decisions can help rebuild Baltic Sea fish, or wipe them out for good.

Last year, EU fisheries ministers decided to continue directed herring fishing in violation of current legislation, despite ICES advice and the European Commission’s proposal for a fishing ban. BalticWaters, and many of us, will be working hard to ensure that last year’s political transgressions are not repeated. This is particularly urgent given ICES’ new advice for herring in the central Baltic Sea, which, compared to last year, is increased by a remarkable 139 per cent.

The implications of the advice for fish stocks and the future of the Baltic Sea are worrying to say the least. Such sharp fluctuations in the advice from one year to the next indicate major uncertainties in the scientists’ analyses. It is important to remember that this situation is not new. We have seen it before – a strong year class suddenly becomes fishable and quotas are increased, only to be dramatically reduced the following year or fishing stopped completely. Management lacks long-term stability that takes into account the development of fish stocks over time.

So, what should Sweden and our politicians do to reverse this trend? BalticWaters points out four measures to act on.

ICES advice for 2025

| Species/Area | Total catch 2023 (tonnes) | Quota 2024 | ICES advice 2025 | Comments |

| Cod | ||||

| Western stock Subdivisions 22–24 | 403 | 489* | 24** | By-catch of cod in flatfish fisheries must be reduced. Reducing by-catch can contribute to the recovery of cod stocks. |

| Eastern stock Subdivisions 24–32 | 1 065 | 595* | 0 | The stock has not yet recovered, despite five years of closure. Cod by-catch in the flatfish fishery needs to be reduced and the amount of cod by-catch in the pelagic fishery needs to be investigated. |

| Herring | ||||

| Central stock Subdivisions 25–29 & 32 | 98 696 | 40 368 | 95 340 – 125 344 | Better recruitment in the last three years than previously estimated by researchers. The stock continues to develop weakly even though there are positive signals. The herring is far from levels where we know that recruitment is good (Btrigger). See ICES roadmap for possible conservation measures. |

| Bothnian stock Subdivisions 30–31 | – | 55 000 | Advice is presented in September. | Advice deferred to September 2024; reference points for the stock to be revised first. See ICES roadmap for possible conservation measures. |

| Riga stock Subdivision 28.1 | 42 800 | 37 959 | 30 394 – 45 235 | The Gulf of Riga herring is a stock in slightly better condition than other stocks in the Baltic Sea, largely due to environmental factors and other fishing rules. |

| Sprat | ||||

| Baltic Sea Subdivision 22–32 | 265 900 | 201 000 | 130 195 – 169 131 | Very low stock recruitment three years in a row. Misreporting occurs, but these effects have not been included in the advice. Misreporting undermines data quality and introduces uncertainty into the advice (see ICES). |

| Salmon | ||||

| Main basin stock, excl. Gulf of Finland Subdivisions 22–31 | 409 tonnes | 53 967 pieces | 0 – 40 000 pieces | Weak stock development.*** |

| Gulf of Finland stock Subdivision 32 | 39 tonnes | 10 144 pieces | 9 440 pieces | Weak stock development.*** |

* by-catch only

** commercial and recreational fishing

*** Read the ICES advice for salmon in subdivisions 22-31 and subdivision 32.

The ICES scientific advice is the first step in the process leading to the Council of Ministers’ decision on fishing quotas in October. Before that, the European Commission presents its proposal in August. It is based on ICES advice and input from various stakeholder groups. Sweden’s position in the negotiations in the Council of Ministers will be decided in September.

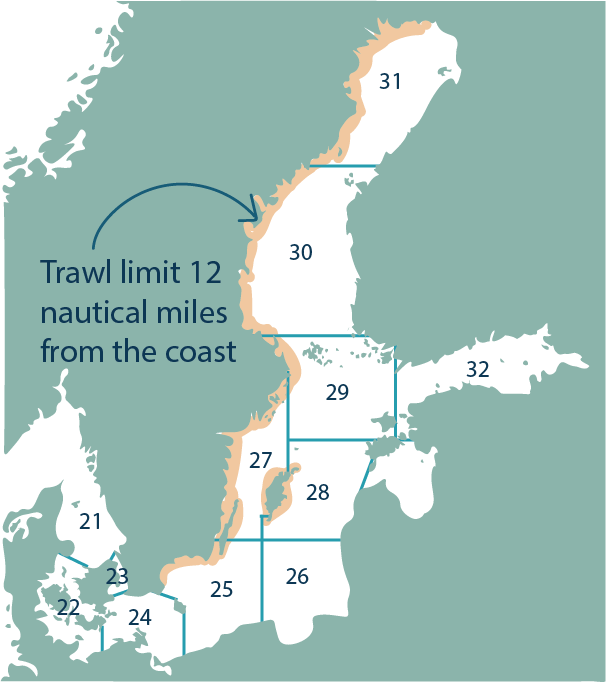

for fisheries. The map also shows the trawl limit

which is now finally proposed to be moved by the Swedish government. Illustration: BalticWaters.

How should Sweden and our politicians act?

1. Firmly push for very low quotas on herring

It is important not to overreact to the new high advice for herring in the central Baltic Sea. Although the stock is developing favourably, this does not mean that it is at a sustainable level. Politicians deciding on next year’s fishing quotas should carefully study and consider the far-reaching consequences that may follow from immediately increasing the quotas, especially as remarkably as ICES proposes.

The reason for the sharp increase in ICES advice is that recruitment (the growth of mature juveniles to the stock) and spawning biomass (the number of mature fish) are estimated to have increased. But spawning biomass is still at very low levels and the researchers’ analysis clearly shows that spawning biomass is below the Btrigger, a warning signal and threshold that, if fallen below, risks stock collapse. It is important to realise that herring in the central Baltic Sea are currently below this threshold.

In addition, ICES informs about the ongoing problem of misreporting in the herring and sprat fisheries where herring is a common by-catch in the sprat fishery. The effects of misreporting have not been included in ICES assessments and advice. This misreporting undermines the advice, something ICES itself is clear to inform about.

For the stock to have a chance of recovering to sustainable levels, significantly lower quotas than those presented by ICES are required. ICES themselves say that their results are uncertain, which should be taken seriously. If the calculations turn out to be wrong, extensive fishing in 2025 risks leading to collapse. Herring may well suffer the same fate as cod did in 2019 – collapse. The western cod stock collapsed after a large quota increase based on a strong year class. Let’s learn from past mistakes and ensure it doesn’t happen again.

During this year’s quota negotiations, EU fisheries ministers need to keep a tight grip on the brake, and be very careful when setting next year’s herring quota.

2. Comply with laws and regulations

Last year, herring recovery was so poor that fishing should have been stopped. Despite this, the Council of Ministers chose to allow a directed fishery of over 40 000 tonnes in the central Baltic Sea. The decision probably violated current legislation. If we are to see a recovery of fish in the Baltic Sea, politicians must at least follow the law and take strong action when a stock is about to disappear. This is a fundamental first step in the right direction.

There is an imminent risk that the herring stock in the central Baltic Sea will collapse within the next few years if the herring quota is set at the proposed levels. Meanwhile, sprat looks set to suffer the same fate as recruitment is ominously low. If herring and sprat collapse, there will be no food left for large predatory fish such as salmon and cod, and these species could disappear permanently.

Whatever happens during this year’s EU negotiations, BalticWaters will follow the process closely. A political and legal overreach like last year cannot be accepted.

3. Prioritise cooperation with Finland and introduce fishing bans where relevant

A common position between Sweden and our neighbours in upcoming negotiations could be effective in reducing fishing pressure in the Baltic Sea. This applies in particular to Finland and Sweden, which, of all the countries around the Baltic Sea, have the longest coastline and take a large part of the available herring and sprat quota. The government should therefore work to strengthen co-operation with Finland and establish a common understanding to protect fish and the marine environment.

During last year’s Council of Ministers, an agreement was reached between Sweden and Finland to introduce a temporary ban on trawling in parts of the Bothnian Sea between 25 May and 30 June this year. But the closure is too short and too late, in practice completely ineffective. In principle, the herring have already been fished out by the large industrial trawlers when the ban comes into force. It is positive that the Swedish and Finnish governments are trying to work together to protect the Baltic Sea and the fish, but it is important that the measures implemented are actually useful.

Sweden’s and Finland’s fisheries ministers should work to restrain quotas on herring and sprat, and urgently decide on a fishing ban earlier this spring. To be effective, a fishing ban needs to take place when the fish gather to rest and later spawn, namely during winter and early spring. This would protect both herring and small-scale fisheries along our coasts.

4. Move the trawling limit further out and expand no-fishing zones

Large-scale fishing for animal feed in the Baltic Sea is the main cause of overfishing. A ban on large-scale feed fishing for herring and sprat is therefore an important first step to address the situation. In recent years, several initiatives have been taken to limit the impact of fishing, but Swedish politicians can still do much more. The initiatives are laudable, but often insufficient.

BalticWaters has long been campaigning for the trawl limit to be moved out permanently along the entire east coast. Yesterday (4 June), the government finally presented a bill where this now seems to become a reality. This is an important and positive step to protect fish and the marine environment. Now it remains to show action.

Another measure the government should urgently introduce is more no-fishing zones – a measure that has proven to be very effective in rapidly strengthening weakened stocks. It can save cod, herring and sprat by preventing collapse and discouraging the depletion of larger individuals (which are important for the reproductive capacity of the stocks). If herring and sprat are allowed to grow and are not fished out of the sea, they can instead become food for larger predatory fish such as cod and salmon. The poor growth of cod appears to be due to the fact that there is simply not enough food in the sea, which can be easily remedied with no-fishing zones protected from trawling.

The government can strengthen the protection of herring by expanding no-fishing zones, both outside Gävle where herring spawn during the winter, and south of Blekinge where the few remaining cod suffer from a severe lack of food (herring and sprat). According to 2023 figures, only 0.8 per cent of the Baltic Sea is strictly protected from fishing, while several Baltic fish stocks are close to collapse.

How are the fish in the Baltic Sea doing?

BalticWaters has summarised the situation for herring, sprat and cod in the Baltic Sea in the fold-out tabs below. The summaries are based on ICES advice for 2025.

Herring

Central Baltic Sea

ICES advice on fishing opportunities for herring in the central Baltic Sea in 2025 is 139 per cent higher than last year. The reason behind the higher set quota is due to a combination of reasons, including that stock recruitment has been better in recent years than scientists previously thought. Therefore, the advice is increased from 41 706 – 52 549 tonnes in 2024, to 95 340 – 125 344 tonnes in 2025 in the Central Baltic. The scientists emphasise that the data used in this year’s analyses are uncertain. In addition, the ICES advice framework does not allow for a stock to recover from fishing after being at a critically low level. Thus, although recruitment for the central herring stock looks slightly better this year, it cannot be guaranteed that the stock will actually recover. ICES analyses clearly show that the number of large individuals continues to decline and that the stock is still below the Btrigger.

Read the ICES advice for the central herring stock in full here.

Gulf of Bothnia

The advice for herring in the Gulf of Bothnia has been postponed and is expected to come in September 2024. The reason is that ICES will revise the reference values used to assess the status of the stock. It is good that values are updated based on the current situation and knowledge of the stock, but BalticWaters also sees a risk in postponing the advice. In September, Sweden’s position is determined in the fishing quota negotiations that take place in October. The fact that the advice is presented in September means less time for analysis and discussion. The risk is that both Sweden’s position and the actual quota decision in the Council of Ministers will be rushed and ill-considered. BalticWaters assumes that the advice will nevertheless be carefully reviewed by politicians and officials in view of the development of the stock.

Sprat

The sprat catch advice for 2025 is 32 per cent lower than that for 2024, due to the decline in spawning stock biomass (the amount of spawning stock biomass, SSB) as a result of recent year classes being among the weakest observed. The last three years (2021-2023) have seen historically low recruitment of sprat, something never before witnessed since ICES was first tasked with informing the EU on the status of fish stocks.

The forecast for recruitment in 2026 looks slightly better according to ICES, which will then result in an expected increase in biomass. However, ICES points out that the sprat stock risks declining if poor recruitment continues – which is possible. It would also mean lower catch opportunities.

Sprat is the main food of cod. Given the poor recruitment of sprat, there is therefore a clear risk that cod will not be able to recover in the Baltic Sea. If there are no sprat in the sea, there is no food for cod. When cod have enough food in controlled environments, they grow very well and can reproduce successfully. The fact that Baltic cod have not yet managed to recover seems to be partly due to the poor condition of the sprat.

Cod

The eastern cod stock is still showing no signs of recovery, hence ICES advises a continued fishing ban until 2025. Even if no fishing is conducted on cod, the stock is expected to remain below the critical limit Blim in the long term, which probably means that the stock can no longer recover, given the conditions prevailing in the sea today.

ICES writes that measures that can support cod recovery include habitat restoration. According to ICES, the focus should be on improving oxygen levels in the seabed and reducing by-catches of cod in flatfish fisheries. A new submission to the Council is that by-catch of cod in the pelagic fishery is unknown, highlighting the Council’s uncertainties and the overlapping risks with fisheries for other species.

A further measure could be to increase the availability of food for cod (i.e. herring and sprat). A recent study carried out under the ReCod project showed that there is no obvious nutritional deficiency in the food available to cod in the Baltic Sea, compared to food from, for example, the Atlantic. The study therefore suggests that food shortages, together with a lack of functioning spawning grounds, may be the main reasons why cod is failing to recover.

Read the ICES advice for the Eastern cod stock in full here.