To better understand the current debate on fishing and the deep divisions between different stakeholders, BalticWaters has investigated how the conversation has evolved over time. Awareness of the impact of large-scale fishing on the Baltic Sea has grown, yet outdated perspectives continue to shape the discourse. This has been highlighted through interviews with scientists, small-scale fishermen, and experts who have been involved in the debate over the past 50 years.

Our inland sea has undergone major changes in recent decades. Many fish species in the Baltic Sea have been affected by overfishing, climate change and other human activities. Commercial species such as cod and herring are particularly affected, threatening both the Baltic Sea ecosystem and the future of the fishing industry.

Today’s fishing dialogue can sometimes feel static, with recurring arguments and decisions being postponed. But a historical look back shows that discussions about Baltic Sea fishing and perceptions of the sea have undergone major changes over time. But today, as the Baltic Sea fish stocks face their worst crisis ever, history reminds us that both the public and decision-makers still have much to learn.

An inexhaustible sea gives no reason for debate

Someone who has long followed the conversation around Baltic Sea fishing is journalist Peter Löfgren. He has been involved in the issue since the 1980s. Back then, the Baltic Sea was home to one of the world’s largest cod fisheries and in Sweden, fishing matters were practically synonymous with cod.

Peter Löfgren at Utklippan, Blekinge archipelago. Photo: Leif Eriransson/Deep Sea Reporter

– At this point in time, the view of the sea was completely different. The Baltic Sea was seen as a rubbish dump and fish stocks as never-ending. Few people had an understanding of life below the surface, says Peter.

The period before the turn of the millennium can be seen as a clear turning point for Baltic Sea fishing. Trawling entered the scene and fundamentally changed fishing. Boats became larger and technology more advanced. The new efficient methods had a major impact on cod stocks, and from the peak in 1984, catches in the eastern stock fell by almost 75 per cent by 2000.

– Despite this, the view of the sea as inexhaustible remained. There was no debate about what increased fishing would mean for the Baltic Sea and fish stocks in the long term, Peter explains.

Criticism of fishing policy emerges

As a reaction to the lack of public debate about the arrival of industrial trawlers and their impact on the sensitive waters of the Baltic Sea, Peter released the documentary ‘The Last Cod’ in 2001. The film examined, among other things, the direct influence that the Swedish Fishermen’s Association had on politics and was met with strong reactions from the industry.

– Fishermen have always had a strong voice and have successfully created a narrative that portrays them as hard-working with tough labour conditions, says Peter.

– This is true for small-scale fishing, but for industrial fishing the reality is completely different, he adds.

The documentary also raised questions about why more politicians had not reacted to the alarming trends in cod stocks, which helped to stimulate political debate. Environmental organisations became increasingly visible in the debate, with many pointing to the collapse of cod stocks in Newfoundland, Canada, as a cautionary tale.

What happened to the Newfoundland cod?

The Grand Banks cod fishery off Newfoundland was one of the world’s richest fisheries and a mainstay of coastal communities in the region for centuries. In the 1950s and 1960s, catches increased dramatically due to technological advances in fishing. Despite early warnings from scientists, overfishing continued and by 1992 the collapse was a fact, leading to a total fishing ban. The collapse had severe economic and social consequences for the region. Despite the closure, cod stocks have not recovered to their previous levels.

Following a scientific assessment last October, the status of the northern cod stock was changed from ‘critical’ to ‘precautionary’, allowing the cod fishery to reopen in 2024 after 32 years of closure.

An early attempt at a cod fishing ban

In 2002, the current government decided to close the Swedish cod fishery. The proposal triggered a major debate about Sweden’s authority to make such a decision. There was strong opposition from the fishing industry, which warned of unfair competition as foreign fishermen would be able to continue fishing in Swedish waters. Even within the Council of Ministers, the EU body that decides on catch quotas, the proposal was met with strong scepticism. While Sweden had begun to question the previous fishing policy, ministers in other EU countries stuck to their previous convictions in favour of continued fishing.

Joakim Hjelm. Photo: Johanna Kozak

Joakim Hjelm, a researcher at SLU Aqua, says that the other EU countries were very surprised when the proposal was put on the table.

Sweden was alone in its position at the time, and the proposal was overruled by the other ministers,’ he says.

While the proposal itself was a political statement, it led to Sweden being ostracised in the subsequent negotiations.

– The strong stance made it difficult for Sweden to take the discussion forward because none of the other countries wanted to cooperate, explains Joakim.

The public interest awakens

Despite an upsurge in Swedish political debate, public interest remained low. The issue gained new momentum when the then journalist, and future politician, Isabella Lövin published the book ‘Silent Sea’ (Tyst hav) in 2007. The book attracted a lot of attention and triggered a wave of public criticism of both fisheries management and politics.

Isabella Lövin says that more journalists started to cover fishing, which increased the pressure on politicians. At the same time, the issue of eco-labelling among seafood companies became more acute as the public began to ask more critical questions.

– I could never have imagined that the book would have such a big impact. Fishing is incredibly complex and it became clear that a whole book was needed to summarise the issue, she says.

Although the book strongly criticised the fishing industry, Isabella found that Swedish fishermen did not oppose it.

– After Peter Löfgren’s documentary, the large-scale fishermen came to the defence, but now the debate became more constructive, says Isabella.

– Possibly because fishermen could no longer claim “that’s not how it is” without facing scrutiny. Or maybe they needed to win public sympathy, Isabella adds.

Isabella Lövin. Photo: European Union/Philippe Stirnweiss

Profitability becomes the guiding principle for national reforms

In the early 2000s, a cross-party political consensus emerged and in 2008, the government presented a strategy that consolidated the idea of using the sea without consuming it. At the same time, resource efficiency and profitability are guiding the multi-stage reform of fisheries management in pelagic (open water) fisheries.

The previous system of two-weekly rations had led to a race where vessels competed to catch as much as they could during the period. There was also overcapacity and a need to reduce the fishing fleet. Axel Wenblad, who helped push through the new reform, explains:

Axel Wenblad. Photo: Private

– The profitability of the fishery was poor and the waste of resources was high. The system was not adapted to the processing industry’s schedule, which meant that some of the fish were discarded at the end of the ration period.

In consultation with the industry, the Fisheries Agency first developed a system of annual rations. After further pressure from the industry, it was soon replaced by an individually transferable quota (ITQ) system. The number of vessels was reduced and the remaining boats were larger and more efficient.

– The idea was that we would have capacity in relation to stocks, but it went completely wrong. We should have put in barriers and demanded more responsibility of the fishing industry, says Axel.

Want to know more about ITQ and its impact on Swedish fisheries?

In BalticWater’s deep dive How we got today’s system for allocating fishing quotas – ITQ, you can read more about how the idea of transferable fishing quotas was born, why Axel Wenblad (then Director General of the Swedish Board of Fisheries) sees the reform as a failure, and possible risks when an expansion of individually transferable quotas for bottom trawling is now being investigated by HaV

Read the deep dive here.

Politicians’ attitude towards scientific advice makes a U-turn

Scientific advice from ICES (International Council for the Exploration of the Sea) has long been part of EU fisheries management and catch quota decisions. Despite this, politicians have often chosen not to act on this advice. But in the early 2000s, there was talk of a change in attitude, when in 2008 the Council of Ministers for the first time chose to follow ICES and the European Commission’s advice for Baltic cod.

Axel Wenblad says he was one of those who actively pushed for a change in attitude to the scientific advice.

– After the quota negotiations in 2008, many of us were very pleased and we were convinced that we had turned the tide, he says.

However, the hopes raised were short-lived. After just a few years, the Council of Ministers abandoned the advice and not long afterwards the stock collapsed.

– The fact that the advice was followed was probably the result of skilful lobbying, which was facilitated by a slight increase in cod stocks, while a rule limited quota increases to a maximum of fifteen percent, says Axel. The later deviation from the advice was due to strong pressure from the fishing industry, he believes.

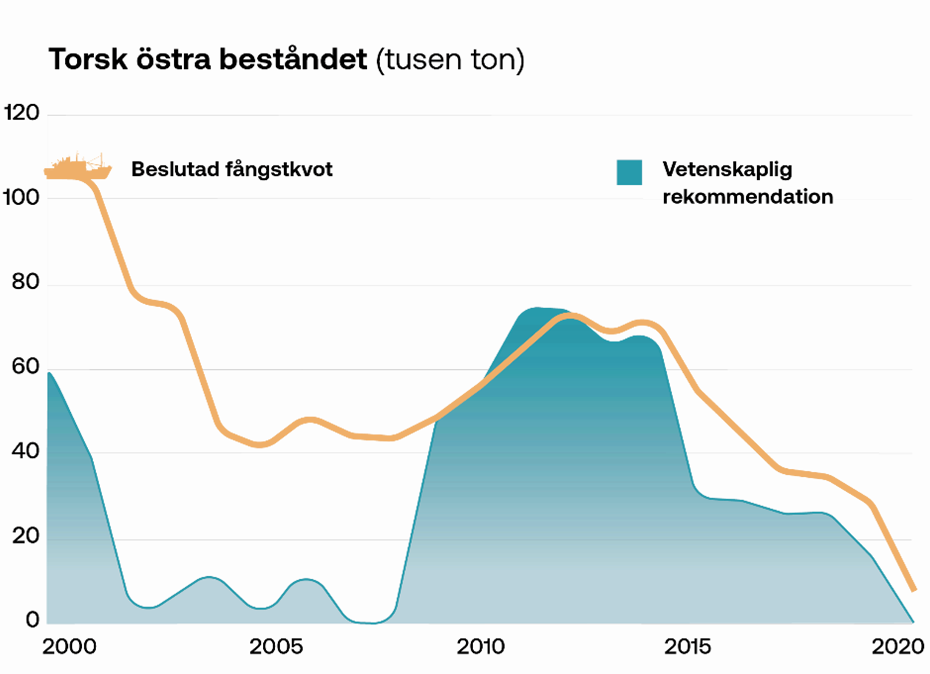

Translation: Torsk östra beståndet (tusen ton) = Eastern cod stock (thousand tonnes); Beslutad fångstkvot = Adopted catch quota; Vetenskaplig rekommendation = Scientific advice

For the eastern cod stock, 2008 was the first year when the agreed catch quotas did not exceed scientific advice. However, in 2013, politicians again chose to disregard the advice.

Source: Faktabanken

Fishing goes from a business to an environmental matter

At the beginning of the 2010s, the view of fishing is changing. With the closure of the National Board of Fisheries in 2011 and the establishment of the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management, the aim is for fishing to be treated not only as a business issue with strong links to industry, but also to take account of the environment.

Daniel Valentinsson. Photo: Jenny Svennås-Gillner, SLU

Daniel Valentinsson, a researcher at SLU Aqua (Department of Aquatic Resources), says that it was at this point that people really began to recognise how fishing for one species, such as cod, affects the rest of the ecosystem.

– People started to talk about how what we see at the coast is connected to what happens in the sea, and several major projects on these issues were launched both in Sweden and in other countries, says Daniel.

Cod continued to be a major issue, but now the discussion broadened to include the impact of fishing on the ecosystem.

– The lack of large predatory fish and the depletion of cod were linked to the increase in sprat and spurdog. And how this in turn affected crustaceans, threatening cod, pike and perch, he explains.

More on ecosystem-based fisheries management

Despite growing ambitions to apply ecosystem-based management, fisheries management in practice continues to handle species seperately. Want to learn more about what ecosystem-based fisheries management means and how it could work in practice?

Read BalticWater’s deep dive: Ecosystem-based fisheries management – utopia or opportunity?

New EU fisheries policy raises hopes

In 2013, a reform of the EU’s Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) was put in place. The reform was seen as an important step towards management that would conserve fish stocks, ensure economic stability for coastal communities and protect the marine environment for future generations.

Isabella Lövin drove the implementation of the reform in her role as a Member of the European Parliament. She describes how the discourse was fuelled by great optimism.

– For the first time, the common fisheries policy took a holistic approach. We thought we had managed to reverse the major destructive trends and there was a great expectation that the situation would improve, she says.

.

Nevertheless, some uncertainties remained about how the new fisheries policy would work in practice. And perhaps the concerns were justified. For while improvements were seen in other European seas, they were absent in the Baltic Sea.

Key objectives and measures of the 2013 reform of the EU Common Fisheries Policy (CFP):

- Maximum sustainable yield: One of the main objectives was to rebuild and maintain fish stocks above levels capable of producing maximum sustainable yield by 2020, a target that has not been met.

- Discard ban*: The reform introduced a gradual ban on discards, meaning that all catches had to be landed and counted against quotas.

- Multi-annual management plans: More emphasis was placed on long-term multi-annual management plans to ensure more stable and sustainable fishing opportunities.

- Regionalisation: The reform gave more power to regional actors by introducing a system of regionalised decision-making.

- Fleet adjustment: The aim was to better match the capacity of the fishing fleet to fishing opportunities in order to reduce overfishing.

- Support for small-scale fisheries: The reform included measures to support and promote small-scale coastal fisheries, which were considered more sustainable than large-scale fisheries and important for coastal communities.

- Improved data collection: Greater emphasis was placed on improving the collection of scientific data on fish stocks in order to make informed decisions.

Researcher Joakim Hjelm points to several reasons for the reform’s lack of success, including the lack of effective enforcement of the new discard ban* (see box).

– The landing obligation led ICES to increase catch quotas, based on the assumption that discards would stop. In reality, however, discards continued, which meant that the fishery received higher quotas while the problem of discards remained, he explains.

It is possible that even the strong optimism had a downside. Journalist Peter Löfgren believes that a certain overconfidence in the reform may have created a false sense of security.

– Many people thought that the battle had been won, which could have contributed to the movement losing momentum. This in turn may have been crucial as the fishing industry continued to lobby strongly and influence political decisions, says Peter.

Not even the collapse of the cod can sway the mistrust in science

A few years into the 2010s, cod stock estimates started to decline more steeply, with both scientists and fishermen reporting increasingly smaller and leaner fish in the Baltic Sea. The term ‘slip cod’ began to be used to describe the abnormally thin fish. ICES urged caution, but despite this, fishing was allowed to continue – until the very end.

Why weren’t the scientists’ warnings taken more seriously?

– You have to understand that the distrust between fishermen and scientists runs very deep. This was the conflict that caused many not to take the warning signs seriously, says Axel Wenblad.

– The new critical situation only seemed to exacerbate the mistrust. The scientists had no explanation for what was happening, which the industry used in its defence, Axel continues to explain.

At the end of May 2019, ICES finally recommended a zero quota for the eastern Baltic cod stock, stating that the stock was below safe biological limits and that recovery would take a long time – even without fishing.

En liten och mager “slipstorsk”. Foto: Jukka Ponni.

The herring alarm goes off – long after the warning bells started ringing

After the closure of the cod fishery in 2019, the focus shifted to other commercially important species in the Baltic Sea, notably herring. Despite the gradual decline in stocks, fisheries management had not shown any major concerns until now. It was considered that the stocks were still strong enough. Was the vision of inexhaustible fish stocks still alive – without lessons learnt from the cod collapse?

With the collapse fresh in mind, one would have expected caution to characterise the following discussion. Yet, the obvious parallels were ignored. Axel Wenblad is sceptical about how the mistakes in cod management have affected the continuing debate on Baltic Sea fishery.

– What happened to the cod should have served as a clear warning signal for those fishing for herring. But the collapse was never properly investigated and few posed the question of what lessons could be learnt, he says.

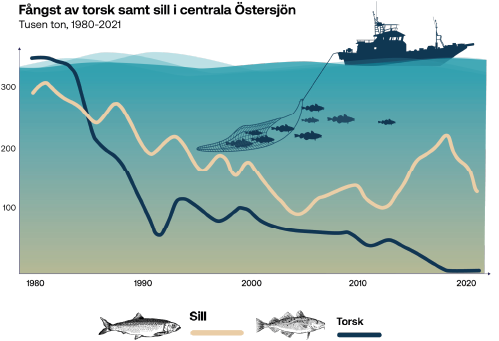

Translation: Fångst av torsk samt sill i centrala Östersjön. Tusen ton, 1980-2021 = Catch of cod and herring in the central Baltic Sea. Thousand tonnes, 1980-2021; Sill = Herring; Torsk = Cod

Source: Faktabanken

Herring development compared to peaks (figures from 2021)

In the central Baltic Sea, herring stocks have declined by over 80 per cent compared to the 1970s. In the last four years, the stock has declined by 40 per cent, and is now at a critical level.

In the Gulf of Bothnia, herring stocks have declined by over 50 per cent since the early 1990s.

In the western Baltic Sea, herring stocks have declined by over 80 per cent since the early 1990s.

Coastal fishermen were beginning to see signs that something was wrong – the herring was getting smaller and they were struggling to catch enough to make the traditional Swedish fermented herring. Manjula Gulliksson, a small-scale herring fisherman off the High Coast on the Gulf of Bothnia, is one of many who has tried to make her voice heard to get Swedish and EU officials to act. She says that small-scale fishermen, whose livelihoods have been severely affected by current fisheries management, have often felt overrun by the bigger players.

Manjula Gulliksson. Foto: Stefan Nordin.

– We have been trying to raise concerns for several years, but the response has been weak. Now, we have finally seen a turnaround in terms of awareness of the impact of overfishing on coastal fisheries, says Manjula.

At the same time, there is a lot of disappointment in the media for not doing more to draw attention to the issue.

– The media often get caught up in the conflict between small- and large-scale fishermen, but avoid the bigger political issues. For example, no one scrutinised the Council of Ministers’ decision in 2023 to allow directed fishing for herring, even though it went against the European Commission’s proposal, she says. However, this was done by BaticWaters, with the support of David Langlet (Professor of Environmental Law at Uppsala University), earlier in 2024 (link to report).

Facts: The quota process for the Baltic Sea fishery in 2023

During last year’s quota process, EU fisheries ministers decided to continue the directed herring fishery in the Baltic Sea despite ICES’ assessment that there was a high risk that the stocks would no longer be able to recover – even with no fishing. The decision was taken in violation of current fisheries legislation (CFP) and despite the European Commission’s call for a fishing ban.

Read more here: Baltic Sea Brief 63: Ministers would rather break laws than save the fish in the Baltic Sea

The debate gains momentum as the crisis worsens

Despite the 2019 fishing ban, Baltic cod stocks still show no clear signs of recovery. At the same time, there are strong indications that herring in the central Baltic Sea are at risk of suffering the same fate, as large-scale targeted fishing for herring is allowed to continue – despite known risks.

Today, we know enough to act, but political decisions are lagging behind. The situation shows that a major shift in the way we think about fishing is still needed to achieve sustainable fishing – where policy decisions are based on science and precaution.

But there are glimmers of light in the darkness. Awareness of Baltic Sea fishing has increased and the issue is gaining greater public attention as more and more stakeholders, organisations and researchers get involved. Even if we are not there yet, Peter Löfgren points out that the debate has become increasingly knowledge-based.

– There are better facts to rely on today compared to 20 years ago, which makes it possible to counter the fishing industry’s arguments in a different way, he says.

Photo: Tobias Dahlin/ Azote

Isn’t one reason for that the fact that the crisis has become impossible to deny?

Yes, Peter laughs sadly. The issue receives more attention now that the crisis is so severe. But compared to the way things were before, those in power are much better informed. The realisation that there is no fishing industry if there are no fish in the sea has started to sink in, which is a very positive development, he says.

BalticWater’s comment:

This retrospection has touched on some of the fishing policy events that have taken place over the last 50 years and is based on the experiences of a number of people. The debate on Baltic Sea fishing has moved from a belief in an inexhaustible sea to a more knowledge-based debate with increased insight into the impact of large-scale fishing on the ecosystem. At the same time, the acute situation of several commercial fish stocks in the Baltic Sea shows that the views that led us to the cod collapse continue to permeate the debate and decision-making.

Decisions should be made based on the best available knowledge. But sustainable fisheries management must take risks into account, not least with regard to the uncertainties surrounding scientific advice. Fixing the Baltic Sea environment and creating better conditions for fish life and reproduction will take a long time and require action on many levels. Reducing fishing quotas is the most effective way to ensure the survival of fish stocks now, it is the only measure we can control in the short term. Today’s quotas are lower than in the past, but stocks are depleted after many years of heavy fishing and much larger safety margins are needed to give fish stocks a real chance of recovery.

Would you like to read more about why we have not made more progress towards a healthy Baltic Sea?

In BalticWater’s report A Policy for a Healthy Baltic Sea, we answer the question of why it is difficult to comply with current regulations, goals and action plans in the marine sector. Among other things, the report shows that the inability of scientists to communicate uncertainties to decision-makers, and low public awareness of the importance of the sea for ourselves and our planet, are significant obstacles.

Read the report here.